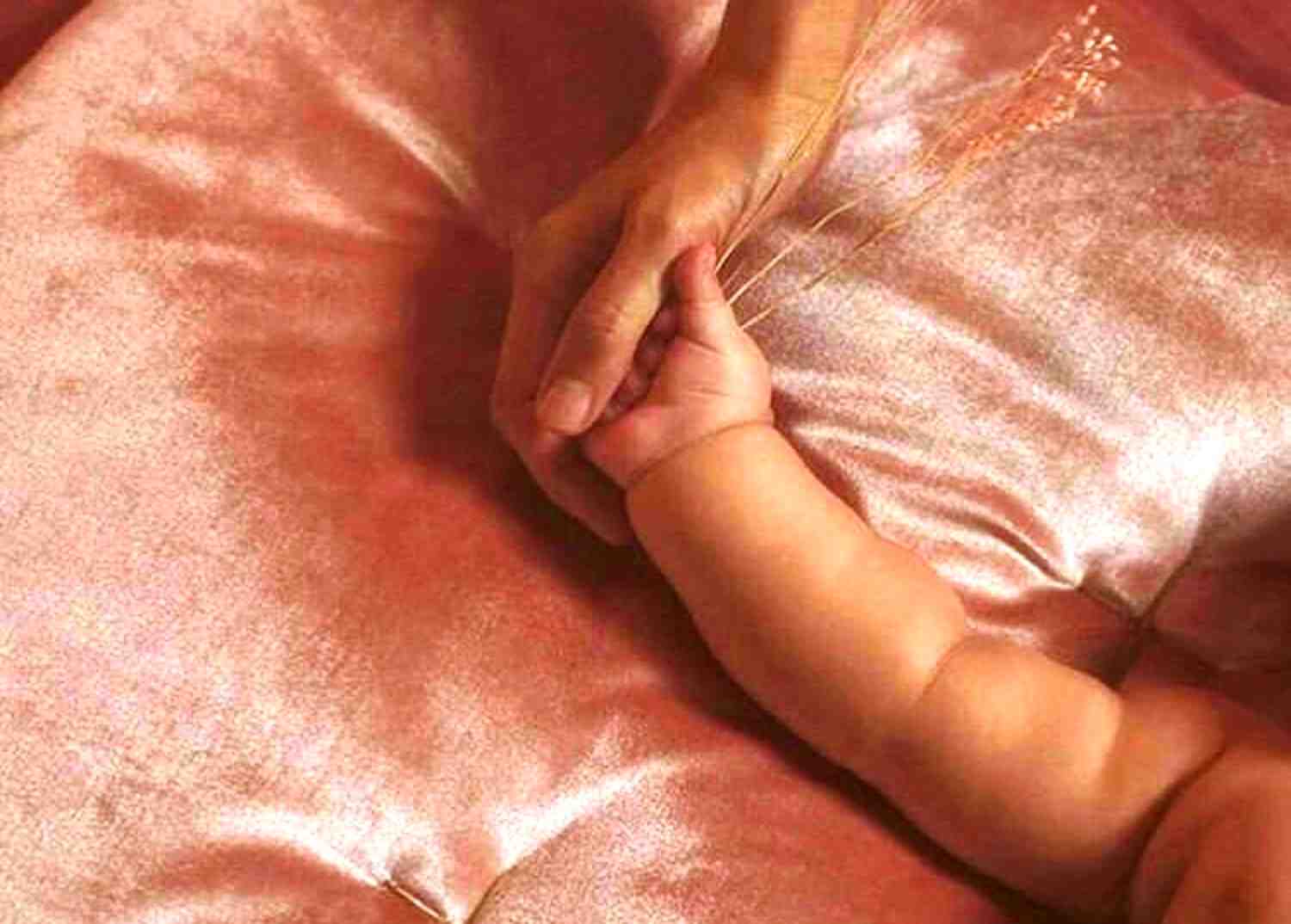

Losing motherhood to ‘tactless’ surgical procedures is creating a new mental crisis in Kashmir. In this piece, the author maps the miserable state and struggle of two Kashmiri women, Sabba and Ameena, whose ‘lost womb’ depression is now becoming a mainstream in the valley, where the situational depression is already taking a huge toll on people.

A little girl in pink dress smiles and giggles, as she plays with colours. She innocently stamps her painted hands on a white piece of chart and creates a colourful impression. Sabba motherly strokes her hair and feeds her the porridge she just made. But just then, the girl starts running away from her. Her sudden sprint snaps a beat from Sabba’s troubled heart.

She pleads her to come back, as she realizes the six-year-old girl is heading towards the edge of a cliff. She tries to catch hold of her, while pantingly running after her. She somehow manages to grab her arm with firmness.

But as the girl turns back, her pretty face disappears into thin air, like a phantom. Sabba looks at her empty hands and realizes that they are covered in blood.

Gasping for air, she wakes up from this nightmare, and frantically tries to wipe off the blood by rubbing her hands against the quilt in terror.

Sabba has these beautiful dreams turning into nightmares frequently. She often wakes up heartbroken, realizing the bitter truth of her life: At the young age of 30, she is braving motherlessness.

To nurse her troubled state of mind, she frequents a psychiatrist’s clinic in Srinagar, where she sits motionless with the lost patient crowd.

Among them is an old man, whose son never returned home after he was picked up by armed forces during early nineties. The weathered man sits sullen in a queue. There’s a pale and puffed woman waiting for her turn, whose 27-year-old struggle to bring justice in her husband’s killing remains elusive. In the same silent queue, a young victim of domestic violence is staring at the front wall.

Back home, Sabba often conveys the feeling of being a misfit in that clinic crowd. But then, she also understands that she needs help.

On her turn, she briskly enters the doctor’s room and tries hard to express her grief of not being able to become a mother. The compassionate doctor counsels her to the best of his ability. But shortly, she comes out with a long face, holding a prescription and medicines in her hand.

Both her face and fate make her appear a hopeless young woman.

ALSO READ: Postpartum depression: The ghost that walks the mind of mothers

Sabba had a major hysterectomy, a surgical operation to remove all or part of the uterus. The surgery may also involve removal of the cervix, ovaries, fallopian tubes and other surrounding structures. She had fibroid, which led to abnormal bleeding from her uterus. To fix her condition, hysterectomy was prescribed and performed.

But the surgical procedure, she laments, made her life ‘barren’. And the very unsinkable feeling has now become a major source of despair in her life.

Her condition has a name: hysterectomy depression.

And dealing with such cases since long makes Dr Bilquis Jameel one of the seasoned gynaecologists of Kashmir. She turns into a biology teacher while explaining Sabba’s mental agony.

“Ovaries are an important part of a woman’s reproductive system that secrete Estrogen and Progesterone,” Dr Bilquis says. “Estrogen is a female hormone, which gets withdrawn after Menopause [the period in a woman’s life when menstruation ceases].”

Once that happens, she says, age-related changes occur in women bodies, like wrinkles, dull skin and weak bones. “Apart from mood swings, many patients also suffer from depression.”

That’s how the ‘inactive ovaries’ bring age-related mood changes in women after they cross mid-forty or fifty age mark. But many young women, who lost their ovaries due to surgical procedures like hysterectomy, end up nursing the womb-related depression in their lives.

“Most of the hysterectomies are performed by doctors, like general surgeons, who’re not gynaecologists,” Dr Bilquis continues. “A patient comes to them and says: I’ve heavy bleeding. And without completely evaluating the patient, hysterectomy is being performed, which’s wrong.”

Kashmir’s major maternity hospital, Lal Ded alone performed 459 hysterectomies in the last two years. The total number of hysterectomies performed during the same period in Kashmir is unknown because most of these procedures are reportedly done in private hospitals. These institutions are reluctant to share data on such cases.

But undeniably, hysterectomy is a life-saving procedure, which comes with depressive side-effects. The surgery is now increasingly sending many young women, like Ameena, into a state of shock.

At Dr Majid Shafi Shah’s clinic at Srinagar’s Jehangir Chowk, the 36-year-old homemaker from Shopian is anxiously waiting for her turn since morning. Accompanied by her 6-year-old daughter, Ameena is on her first consultation visit to Dr Majid, who’s a psychiatrist working at the District Hospital, Pulwama.

She complains of palpitations, restlessness, sleep disturbances and flashes for more than two years now. Ameena has undergone hysterectomy for uncontrolled vaginal bleeding three years ago at a local nursing home. Since then, she has had other health issues.

Her husband, who’s a mason by profession, has to also indulge in the household chores due to Ameena’s condition.

Dr Majid diagnosed her with a major depressive episode, with vasomotor symptoms of surgical menopause with anxiety features. Ameena is prescribed medication and referred for counselling sessions to the clinical psychologist.

“Many women who undergo hysterectomy for different reasons actually suffer from co-morbid conditions like depression and somatisation,” Dr Majid says. “They’ve expectations of improvement and resolution of symptoms related to their depressive condition.”

However, there’s an increase in symptoms of depression and anxiety after the surgery. “These women need individual treatment for these conditions,” the doctor advises.

The fact, however, remains that surgically-removed wombs and the feeling of motherlessness create a perpetual trauma in these women, as their struggle for relief remains never-ending.

In lieu of relief, Sabba often hires an Auto—a three-wheeler—to visit Makhdoom Sahab shrine in Old Srinagar.

Climbing the long-winded stairs, she buys corn kernels to feed the pigeons. As she enters the door of the saint, tears start falling off her face. She sits beside a pillar and her words give life to her agony, “Ya Allah, what do I do with this pain! Where shall my heart find relief! How shall I be hopeful of something impossible!”

A visit to the shrine gives her momentary relief, before the heart-wrenching cycle begins again with the girl in pink dress.

Like this story? Producing quality journalism costs. Make a Donation & help keep our work going.