Sudden occurrence and subsequent jail faced by a mentally-unsound person in Lal Chowk recently opened a low-key debate about the larger plight of mentally-challenged persons in the “world’s most beautiful prison”.

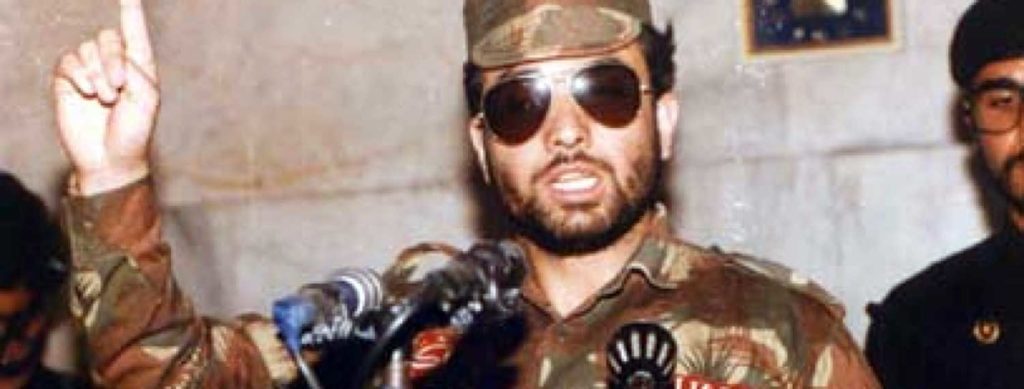

War against the Indian state was still fresh in Kashmir when a Kalashnikov-wielding boy came running inside the Hazratbal shrine in early nineties with a kill message. Inside the sanctum sanctorum sat the man who till 1987 was an active street fighter and now, commander-in-chief of Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF)—the militant outfit fighting for Independent Kashmir.

Javaid Mir, the chief, got the message, and at once began cursing the Indian forces going berserk in the valley in their pursuit to hunt militants and their sympathizers. The news was about a new Kashmiri killing—but clearly, a departure from the usual. This time, a mentally-unsound person, or Mott, personally known to Mir, was killed. Some smoking guns rattled in retaliation, but such knee-jerk reactions never ended the military nightmare—that was now making the poor tribe of Mott cannon-fodder of the war.

Some 27 years later, Mir—now a weaponless commoner bereft of yesteryear’s commander charisma—was roaming in Srinagar’s trade heartland Lal Chowk, when he suddenly witnessed traders downing their shop shutters in panic. He curtly learned that a mentally-unsound boy had triggered a fidayeen-type scare in his moment of madness and faced abrupt jail despite passerby’s protests.

Mir flashed no different outrage than he did over the Mott killing in the 90s. But with his smoking guns long rendered defunct, he eschewed his rage for the fear of being dismissed as toothless aggression. In disgust, he walked away.

“Somehow that mentally-unsound boy captured in Lal Chowk reminded me of the Mott whom we would teasingly call tschar-e-kal’le [sparrow head],” says Mir, recalling the fate of the Mott killed in 90s. “The only crime of that poor soul was that he had picked up a grenade abandoned by a fleeing militant group trailed by BSF party at Srinagar’s Kak Sarai.” The grenade in his hand, Mir says, was enough a hint for the paramilitary forces—involved in many brutal massacres in valley—to gun him down with impunity.

What happened—then at Kak Sarai, and now at Lal Chowk—perhaps served a larger reminder of how even mentally-unsound persons found themselves grappling in Kashmir’s security dragnet. Various agencies and organisations documenting war abuses in Kashmir still lack the statistics and data about this particular class of casualty. Even somebody like Shakeel Bakshi—a conscious record-keeper of K-sufferings—terms the area still unexplored. On contrary, he says, piles of documents and research has been already done on how the war derailed mental setup in Kashmiris.

He talks about one Abdul Majid Mir, 35, of Lagripora Dorparah Sopore. “Till date,” Bakshi says, “I have failed to understand why army killed that mentally-unsound man in 1997. Not that army needed a reason to kill anyone in the Vale then, but killing an unarmed Mott was indeed an atrocious act.” He shows details of Banihal’s Bashir Wani, a Mott killed by army in 2002, followed by two successive Mott killings in Tral—respectively done by army’s 22 Rashtriya Rifles in 2005 at Mazbugh and BSF’s 173BN in 2006 at Batgund Tral.

Then in April 2008, another case detail shows, a 24-year-old mentally-challenged youth, Shakeel Malik of Boniyar Uri, was shot dead by the army when he tried to sneak into 22 Rashtriya Rifles camp in Mazbug village. The case carries a signature state remark: police registered a case as army termed the incident as ‘unfortunate’.

Bakshi momentarily stops to recount the fate of one Badshah Khan—a Mott—in his hometown Batamaloo, a no-go military zone till 1993. Khan would walk on streets like a happy-go-lucky man — be it curfew, crackdown or civilian shutdown. “One day,” Bakshi says, “to everyone’s shock, forces shot him dead .” He pauses to say, “It never made any sense — like, it never did, in thousands of other Kashmir killings.”

Far away from Batamaloo, then Handwara had become a military post where the twin January 1990 massacres had terrorised the town to an extent that hardly anyone would go against army begair—the modern day forced labour having treacherous shades of the inhuman bygone Dogra practice.

One day when an army pickup truck near the army watchtower in the main bazaar was about to ferry natives for forced laibour down in a northern garrison, a bleeding man appeared on the scene and stunned everyone. Fireworks had resounded in the area some minutes back. None had made sense of them until the man appeared on the scene and created scare. In the crowd stood Ess Ahmad Pirzada, the man who would later become the author of Wadai-Khoonaab—the book documenting 2010 Kashmir killings.

“That bleeding man was a local Mott,” recalls Pirzada. “He was shot by forces in nearby Kulungam and had carried his wounded self to the town where he died upon reaching.” Perhaps for the fear-stricken commoners, says Pirzada, the killing was yet another reminder that the war was going to spare none—“absolutely none”. In other words, he says, the line of distinction had blurred.

Those days in Handwara itself, Pirzada would spot one handsome teenager who would flaunt long tresses otherwise a signature style of Afghan militants—the guest mujahideens. Something about that boy had made him the dearest of the town. He was mentally-unsound, a darling Mott, as Pirzada knew him.

“One day the same boy unwittingly walked into a trap—an ambush—laid by army and in the next instant, the locals saw him dead on ground. They shot him despite knowing that this boy was no stranger around and did not even have remotest connections with militancy.”

But the gunners, enjoying complete impunity under Armed Forces Special Power Act (AFSPA) had their own reasons to kill the boy. For them, he was a “potential terrorist”.

“Such killings and then subsequent labelling to pass them as terrorists,” says Khurram Parvez, a rights activist, “only show how Kashmir is in the grip of an ugly occupation.” Equally ugly feature of it, he says, is its devastating impact on families—like on the family of Tral’s Taja.

In 1995, Taja’s son, Nazir Shah, 30, had isolated himself amid unabated killings outside. In his Tral hometown, people knew him a mentally-unsound person. But for his mother, Nazir was a Mott, who was into poetry and mysticism.

It was a happy family before killings decimated it. First Taja’s brother was killed by soldiers, followed by her husband who fell to the ‘anonymous gun’. “Her tears were still moist when Indian soldiers appeared and killed her mentally-challenged son, Nazir,” says Imtiyaz Mir, a neighbour. Then a teenager, Imtiyaz saw the mother frequenting her son’s grave only to cry a river there. “When even tears failed to console her, she stepped into her son’s shoes.”

Taja began writing poetry, mostly elegies, in longing for her son. “Through verses, she believed, her son was in touch with God. And now, through the same verses, she tried to stay in touch with her slain son.” At times, the neighbour says, the mother would rise before dawn and would compose poems in the longing.

In the same state, some years ago, she passed away, leaving behind a large volume of verses and couplets. No sooner did she die, a boy from Shareefabad Tral walked into a nearby jungle, leaving behind everything, including an American scholarship, to wage a new age war in Kashmir against the Indian state. That boy was Burhan Wani, born a year before Taja’s poet-mystic son was done to death in Tral.

Over such killing, even the state apparatus seemed to be in no slumber. One top counter-insurgent in the league of STF’s founding boss Farooq Khan—now a BJP leader—recalls something very disturbing about June 26, 2001. That day army Public Relations Officer sitting in Badami Bagh Cant had shot a somewhat ‘triumphant’ handout to Srinagar’s Press Colony, reading: Two infiltration bids foiled in Kashmir, 11 killed. Those were intruders, the statement said, who first opened fire in the remote Tengdhar-Karnah and Machil sectors—Kashmir’s northern hinterlands synonymous with killing fields, where infiltration bids and subsequent covert kill Ops are as old as the Kashmir insurgency itself.

But that day, as the counter-insurgent on cusp of retirement recalls, the PRO failed to explain: why did the forces kill a mentally-retarded person at Devar Lolab? “That Lolab man could have been spared,” the counter-insurgent says.

“But then, I believe, every war has its stray sides…”

“Just like stray bullets?”

“Yes — I mean, in Kashmir, where our motto is to weed out every possible rebel remnant, such things happen.

But having said that, I don’t think anyone is proud of what happened at Lolab that day.” But despite this spoken regret, the fact remains that Lolab was repeated many a times over in Kashmir.

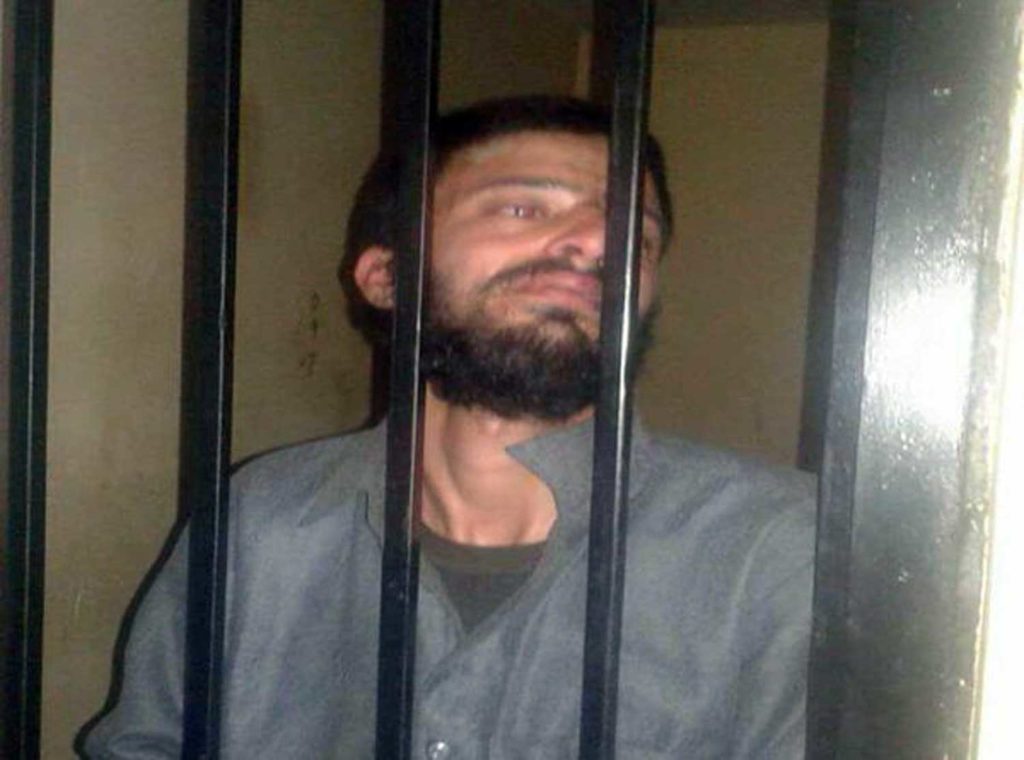

In 2011’s peak summer, the then Chief Minister Omar Abdullah—and Unified Command head—faced major embarrassment when the army and police claimed a “top kill” who turned out to be a mentally-challenged civilian. The postmortem revealed that the victim was a Mott from Reasi, identified as Ashok Kumar and passed as a “top Lashkar-e-Taiba militant Abu Usman alias Abu Adnan alias Doctor”. A speedy fact-finding revealed that he was taken to Surankote forests in Poonch district where he was killed in a 12-hour long staged shootout.

Once the word spread, police swiftly booked the culprits – soldier Noor Hussain and cop Abdul Majeed – for murder charges. The duo had followed a system in which the reward money is given to soldiers and police personnel for killing militants. But they had given wrong information for getting cash reward, Abdullah Jr admitted.

By swiftly blaming the duo, Omar Abdullah thwarted a major crisis, like the one that had last gripped his government in summer 2010, when army killed three men in a Machil fake encounter case and he faced the uprising. When asked how it was possible to recover arms, as claimed by the forces, from the slain civilian, Abdullah had his curt reply up his sleeve: “Clearly more questions are raised than answers are available right now…” Neither Abdullah nor his forces explained it any further.

But the same Abdullah demanded speedy answers last fall, when forces targeted a mentally-challenged man, Mott, with pellets in Srinagar. Showkat Misger of Safa Kadal area was brought to a Srinagar hospital in a profusely bleeding state with pellet injuries on face, skull and eyes. Doctors said that the middle-aged man had suffered brain damage due to pellets. At the hospital’s trauma theatre, the agitated and horrified man—vomiting blood due to injuries—refused to settle down for a surgical intervention and wanted to leave the hospital.

By then, PDP-BJP regime headed by Mehbooba Mufti had piled up 80 bodies across the Vale, blinded hundreds and wounded over 10,000 in a vicious security crackdown aimed at “controlling streets from stone-pelting youth”. Amid bloodshed, Modi’s NSA and ex-sleuth who reportedly gave the dreaded counter insurgent Kuka Parrey to Kashmir, had become the talk of the town because of his much-hyped Doval doctrine: an aggressive assimilationist strategy to end talk on Kashmir’s political status. The crackdown as per the Doval script was designed to convince Kashmiris that they will need to reconcile for assimilation, even if it involves the use of force. Now, when people like Showkat Mott were bleeding on streets, the doctrine appeared more than a paper work.

“But what threat did a mentally challenged person pose to the integrity and sovereignty of the country that he had to be shot so mercilessly?” NC sought explanation in 2016 just like PDP did in 2010. “Was he attacking an army camp or trying to ‘buy milk or toffees’ from a Police Station as insensitively mocked by Mehbooba Mufti? Repression seems to be crossing all limits as the political narrative is getting more and more reductionist and regressive by each passing day.”

NC’s political nemesis, PDP—“now playing upgraded version of Omar Abdullah of 2010”—was quick to remind NC about its last CM’s first killing: a mentally-unsound person at Gupkar in Jan 2009.

Termed as mentally-unsound person, Abdul Rashid Reshi, 34, was shot dead by army personnel few meters away from the residence of Omar Abdullah at Gupkar Sonawar. Coming from Veer Saran village of Pahalgam, Reshi was in Srinagar to earn bread as a labourer. Police said he was shot after entering the army camp by scaling a wall. But how someone not-so-normal went that far up in a high-security street of Gupkar was never explained.

But in every war, says a top cop known for his peace policing, offensive happens. “You see when German bombers were terrorizing London in the beginning of World War II,” he delves into war history to strike semblance, “US President Franklin Roosevelt asked British Prime Minister Winston Churchill: ‘What should the conflict be called?’ To which Churchill replied: The unnecessary war. Thing is, we are in the middle of the same ‘unnecessary war’, which at times makes no distinction…”

“Not even acknowledging someone’s mental ailment?”

“Perhaps I didn’t leave anything unsaid, did I?”

But for commoners, when the same unnecessary war makes no distinction between mentally sound and unsound—then, as JKLF chief Yasin Malik told me sometime back, they tend to cut loose to undo it. “Why do you think more and more youth are now attacking encounter sites that would otherwise instill fear in them in the past? They do it to end the murderous status quo they live in,” Malik told me. “They want freedom as much as they want these injustices to end.” Even unionists at times have questioned such killings.

When a Jammu-bound Tanveer Sultan—a police station regular for his militant past— was stopped and killed in Kud town by forces on June 13, 2016, the ruling party lawmakers raised suspicions. What the police described as militant killing was contested by his family in Bemina. Sultan, they said, was a mentally-unsound person. “He was on his way to Amritsar for treatment when intercepted and killed.”

Sultan is long dead, but some in his tribe are still missing. Their families say they disappeared in custody, like Ghulam Nabi Shah of Nambla Uri. The family of this mentally-challenged person says that their son disappeared after being picked by 5 Gadwal Rej in 2001. When last checked, the Shah family was seen sitting in a monthly APDP sit-in inside Srinagar’s Pratap Park. Like others, they too were seeking his whereabouts. He might not return, but some disappeared Mott did return—dead—like a Mott from Rainawari last summer.

Fayaz Sofi would often sit in a local graveyard or in a playground in Rainawari till the day Burhan was killed. He would walk back home to Naidyar in the evening. But when he didn’t return on July 9—the bloody day when around a dozen Kashmiris were shot dead in pro-Burhan protests across Valley—the mood changed in his home. Despite filing an FIR, Fayaz was not traced for over a week before a cop called and directed the family to identify a body at Kangan. It was him.

When the disappeared returned dead, the family accused the forces of killing their son, a charge denied by the police. Now, the family isn’t seeking ‘elusive’ justice, but an answer to their question: if it was the case of drowning as the police termed it, then why were our son’s hands tied and how did those serious injury marks appear on his body?

Perhaps Omar Abdullah has long addressed such questions when he faced one over the 2011 Suronkote staged shootout where a Mott was passed as militant, “Clearly more questions are raised than answers are available right now…”

Back in 90s at Hazratbal—JKLF’s bastion of yore—another Kalashnikov-wielding boy had come rushing inside with a message for the boss sporting black goggles, camouflaged jacket with JKLF insignia and a military beret cap.

Javaid Mir recalls it a chilling day of January 5, 1991 when instead of a usual kill message, came the gut-wrenching news. Troops, he was told, have raped a mentally-unsound old woman in her Barbarshah Srinagar house. Known for his knee-jerk reaction, Mir, who fired a rocket launcher at Srinagar’s Tattu ground to prove Governor Jagmohan wrong—“I have broken JKLF’s neck”—after Yasin Malik’s detention, reacted with smoking guns, again.

But the ‘action’, as they would call it then, hardly gave justice to the old lady who died in 1998, while the FIR still awaits action from the state government.