The ex-Punjab police chief KPS Gill’s role in crushing the Khalistani militancy might be well known, but his Kashmir counterinsurgency imports have largely remained under the security layers, even after his demise.

Some old chips of Kashmir’s counter-insurgency block still recall how one of their bosses accused of rights violations would often meet his “idol and inspiration” to scuttle Kashmir insurgency on pattern of Khalistan.

That buoyed IPS officer from Pir Panjal would later reflect on many of his one-on-one meeting with Kanwar Pal Singh Gill—popularly known as KPS Gill, the ‘supercop’ who had “much blood on his hand”. Out of those secretive meetings, the cop imported Gill’s method in the Vale and implemented it to kick-start counterinsurgency operations in J&K.

That IPS guy was the notoriously famous counterinsurgent chief Farooq Khan, who is credited with establishing and successfully leading the anti-militancy operations in Jammu Kashmir in the nineties through the STF, Special Task Force.

When Gill passed at 82 due to cardiac arrhythmia at Delhi’s Sri Ganga Ram Hospital on May 26, Khan was one of the first mourners. “He [Gill] was a torch bearer for anybody who was ready to sacrifice his life for the safety and security of the country,” said Khan, now a BJP leader and an administrator of the Union Territory Lakshadweep.

Notably, Khan spared those remarks for someone about whom a Sikh scribe famously wrote in 1994: “when the history of the fight against insurgency comes to be written, Mr. K.P.S. Gill could well be judged (by those partial to him) as one who restored order at the expense of law.” Somewhat similar tactics—restoring ‘order’ at the expense of ‘law’—drove the former STF chief’s combat Ops in Kashmir.

Khan’s fanboys and detractors now recall how the ex-counterinsurgent went after the non-militant support in a bid to crumble the ‘societal Stockholm Syndrome’. “Those involved in feeding, harbouring and supporting insurgents came on his radar,” says Khan’s former colleague. “Those who floated forums to take up the rights of detained militants, also faced STF hitting.”

But even his colleague agrees: Khan wasn’t doing anything new. He was simply following his master in Kashmir, who largely reined militant groups by regrouping the police force and resorting to strategic shift, the colleague continues. “And like Gill, Khan also held good intelligence at the heart of his action.”

However, before becoming Khan’s “idol and inspiration”, Gill had his share of butchery in Punjab. His role came after the then PM Indira Gandhi ordered the Operation Blue Star to gun down Bhindranwale and his supporters at Amritsar. Later, in 1988, Gill commanded Operation Black Thunder to flush out militants hiding in the Golden Temple.

For this Sikh officer, the Sikh militancy for creation of Khalistan was actually a rebellion of a “privileged quasi-federal caste-based orthodoxy that saw its privileges shrinking.”

Once he made a comeback as Punjab police chief in 1991, he was blamed for fake encounters — the damned combat drill that shortly became a ‘norm’ in Kashmir.

“Then in the Valley, Gill’s appointment to combat militancy was on the cards,” says a former Raj Bhawan official, now holding a top position in the government. “But governor KV Krishna Rao scuttled the move. Apparently, he was mindful of the fact how Gill hated to take orders while having his own way.” On the Gill question, however, the PM Rao chose to reaffirm his belief on his fellow Andhra man, governor Rao. But Gill remained his favourite cop.

Within six months after becoming the prime minister in 1991, Rao had brought Gill, then chief of the Central Reserve Police Force, back to Punjab for resuming the “democratic process” in the violence-torn state. “PM Rao,” as Gill would later recall, “never interfered in policing.” With the result, Gill crushed the militant movement quite ruthlessly.

Rao wanted to do the same in Kashmir, the ex-Raj Bhawan official says, where he initially couldn’t get the choicest results despite “having perfect Kashmir knowledge.” He wanted to play his political stroke at a right time. The time came by mid-nineties, when the election commission announced the parliamentary polls. What Rao did left nothing unsaid for the imagination.

In that period, a momentarily lull ensued in Kashmir. No gun rattles, no dissent demos, nothing—until suddenly on March 24, 1996, a fierce encounter began at the Hazratbal shrine. But before Khan’s STF could gun down all the 32 activists of the Amanullah faction of the JKLF inside the Hazatbal shrine, including its chief, Shabir Sidiqui, PM Rao had addressed the crowd from Delhi’s Red Fort, saying he intended to do a “Punjab” in Kashmir.

Many called it Kashmir’s Operation Blue Star. But, one question beguiled all: what was actually happening?

“Khalistan was happening,” a top intelligence officer says, “based on the Gill doctrine.” Earlier, the same doctrine had reined in the militant groups in Punjab. Years later, when the highway insurgents did Gurdaspur, many wanted to dust up the doctrine to deal with it. “Gill doctrine is a combat strategy, asserting that counterinsurgency doesn’t merely remain a ‘law and order’ issue when insurgency becomes a full-blown warfare in the garb of a political rebellion,” the intelligence officer continues.

Unlike the Doval doctrine—“an aggressive assimilationist strategy to end talk on Kashmir’s political status”—Gill doctrine asserts that rewarding insurgency in one theatre of conflict will be replicated in others. (Earlier, both Doval and Gill—“as best bets of Delhi”—had rubbed shoulders in Punjab’s war theatre where they came down heavily on its militancy.) But how Gill’s Punjab counterinsurgency tactics found home in Kashmir is quite intriguing.

Gill had exploited what he called the “Jat Sikh mentality”. He rounded up young Sikh boys who had seen their loved ones “killed by Khalistanis” and gave them license to go after them. It was this horrific saga spearheaded by Gill that crushed the Punjab insurgency.

The similar fatal model was implemented in Kashmir where many delusional insurgents and the “victims of the insurgent violence” were encouraged by the security apparatus. Those gunners called Ikhwanis were given the license to go after the armed rebels and their sympathisers, like those Sikh boys in Punjab. It was indeed happening on the pattern of Gill’s anti-Khalistan recruit philosophy, based on two principles — fear (of further losing lives of their loved one) and revenge.

“The common notion then prevailing was that the leaders of militant groups must be dealt with militants and criminals,” says one senior police officer. “It was the part of the Gill doctrine, equating militant appeasement with rewarding terror.” Then the main enforcer of this doctrine was Doval, then reportedly cooling his heels in the Vale with militant profiles, including that of Hajin’s Kuka Parrey. What followed next is the history of Kashmiri counter insurgency, a dirty people versus people war.

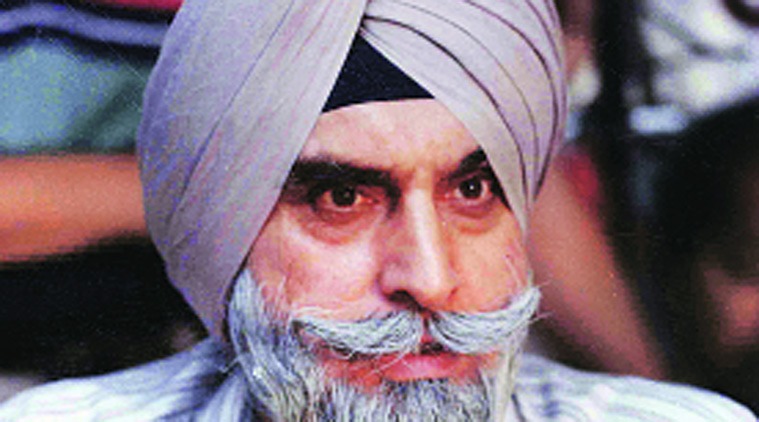

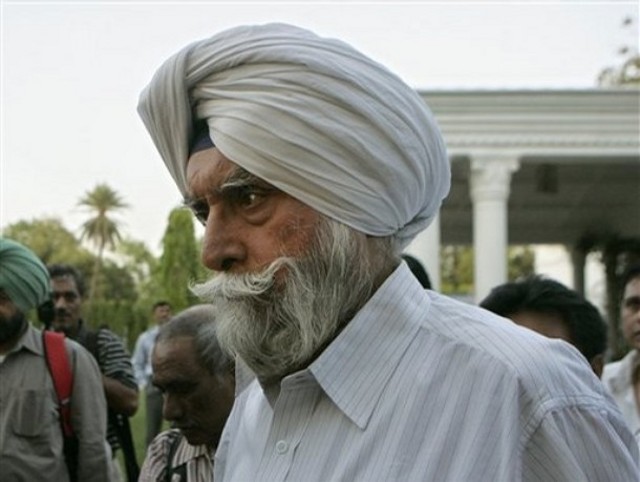

Photo: Javed Dar

But for Delhi, Gill was the ‘Lion of Punjab’, awarded with a Padma Shri for his counterinsurgency role. The moment he retired in 1995, he became an author, a speaker and a consultant on counterinsurgency, especially on Kashmir.

“Wherever there is violence, it seems the murderer Gill shows up,” the Council of Khalistan once said when Gill was appointed as CM Modi’s advisor to help his government to check communal violence in Gujarat soon after the 2002 riots. “The Indian government previously used him to commit its genocide against his own Sikh brothers and sisters in Punjab, Khalistan, and then they used him to commit genocide against the people of Kashmir.” For this reason, he was termed “far worse” than any of those people at Aushwitz.

On camera, however, he came across as a cold man—having no remorse, whatsoever. Yet, he would regularly face a volley of questions, like—“Mr Gill, do you sleep? Do you have any regret in your life?” To which, he would interpret Guru Nanak’s philosophy and life, “I am a very devout Sikh.” Even in Kashmir, where he always advocated his rough-and-ready methods to end insurgency, his devotees would imitate him on his religious beliefs, too!

But a self-styled advocate of Kashmiri Pandits would get animated over Kashmir’s human rights activists’ campaign. He even accused the rights defenders of having links with external separatist forces. “For better handling of the Kashmir situation,” Gill once said, “one has to study the prevailing situation and take measures keeping in mind the collective psyche of Kashmiris.” He batted for the evolutionary tactics, arguing that the measures adopted to quell insurgency in 1989 wouldn’t have been valid in 1991. And yet, he behaved no better than the unbending military regime on the controversial legislation like AFSPA.

In 2014, as then-CM Omar Abdullah advocated AFSPA removal from certain parts of valley, Gill vehemently opposed the move. Then, a regular at VHP functions, he told the World Hindu Congress: “I think there is a propaganda against AFSPA.” Kashmir, he argued, is a “terrorism” problem, where the law must stay.

In fact, he wouldn’t denounce the mutilated corpses (that are so often projected through the media) as the symbols of what the incumbent army chief Bipin Rawat says is a “dirty war” in Kashmir. Instead, the images of Dukhtaran-e-Millat and Hurriyat paying homage to the Mehmaan Mujahiddeen and to Pakistan qualified as the most tragic depiction of the Valley. The chronic Pak-basher would often quote an Israeli-American political scientist, Yossef Bodansky, on Kashmir: “For Islamabad, the liberation of Kashmir is a sacred mission, the only task unfulfilled since Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s days.”

He remained critical of India’s reliance on ‘the niceties of diplomacy’ to resolve the Kashmir problem. In fact, when the mercy petitions of Khalistani militant Devinder Pal Singh Bhullar and Kashmiri convict in parliamentary attack case Mohammad Afzal Guru were turned down by president of India, Gill advocated the need for a law which makes sympathy with such causes an offence—something which was done in the post Nazi Germany. He batted for the decision of Indira Gandhi, who rejected Maqbool Butt’s mercy petition and hanged him as soon as the Kashmiri fighters demanding his release killed an Indian diplomat Ravindra Mhatre in Birmingham in 1984.

For his hardnosed posture, many in Delhi even suggested that Kashmir also needs a KPS Gill for reforming the disgruntled Kashmiris. In fact, on Oct 17, 2016, amid the cries of “time to revive a Kuka Parrey-type group in Kashmir”, the ex-Hizb-ul-Mujahideen militant Zakir Musa in a video message made a surprising mention of KPS Gill while saying how many Sikhs “are requesting” to join Hizb.

“About for our oppressed Sikh brothers,” Musa said, “over 12000 of whom were killed by KPS Gill in operation Blue Star in Punjab, they too want to take revenge from India. We have received many requests from our Sikh brothers to let them join us. We are with them on every front. God willing, we will try and make an exclusive group for Sikhs.” Apparently unmindful of the likes of Farooq Khan’s conduct in Valley, Musa even said that India wanted to repeat the Punjab in Kashmir.

However, there was another reason why Khan sent those quick condolences to his “idol” from the faraway land he now heads.

Akin to Gill’s tactics, focusing on operations which targeted the leadership and cadre of Khalistan militant leadership, the same holds true even in the case of Kashmir, where Khan’s STF succeeded in coming down heavily on the militant leadership.

Perhaps that’s why the former counterinsurgent chief while condoling the passage of another former counterinsurgent chief termed it a “personal loss”. “I gained immensely from his guidance and advice,” Khan said, “that helped us in fighting militancy in the State.”