‘Namaloom Afraad’ or unidentified gunmen, not new to Kashmir, came back into the discourse after Lt. Omar Fayyaz’s death. With their recent resurrection in Pulwama, and the assassination of two ‘affiliated’ men, the nightmare returned to haunt the haunted.

A tinge of tension persists in the house whose headman fell to the ‘anonymous gun’ more than a month ago in Pulwama. Long faces of bewilderment coupled with the unspoken wrench leaves one obvious question behind: who killed Mohammad Yousuf Lone—a man full of life till his last twilight, when a bullet burst sealed his fate.

Among those long faces, the slain’s sibling, Abdul Ahad Lone recalls May 18 as a fine day when the departed was joyously roaming around. Then in the late evening, he says—as bewilderment grows on the faces inside the room—things started heating up in the dusky Gundroo and Hakripora villages of Pulwama.

At around 10pm, Ahad heard gunshots. “There was no retaliation,” he swiftly states. The next thing he recalls is his (long) panting, pre-dawn run to his neighbouring Hakripora village from his native Gundroo. He was rushing fast to take his brother home, dead.

Who killed him?

“We have no idea,” Ahad, a carpenter, says. “But yes, there were forces all over the place that day.” In the media, it was said that Namaloom Afrad (unidentified men) killed him. Militants in their statement said that they didn’t do it. They termed him their ‘close friend’. The militants came to pay him homage through their ritualistic gun-salute. Among those who turned up on his funeral to offer the insurgent insignia honour was the Lashkar’s Kashmir chief, the indefinable Abu Dujana.

Ahad says his sibling wasn’t a militant, but “wothan behwaan aus teman seeth” (He was in contact with Lashkar).

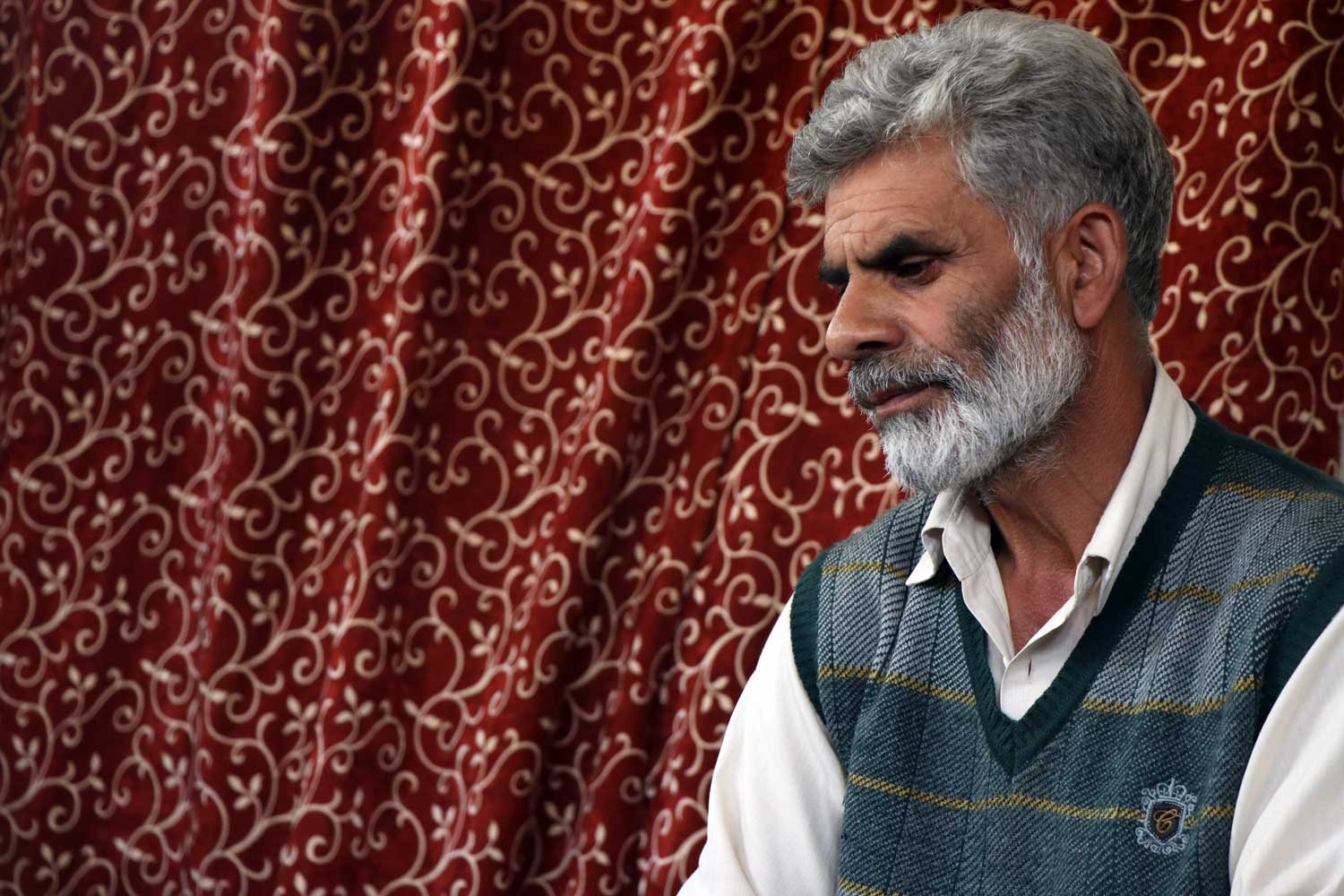

Abdul Ahad Lone, brother of Mohammad Yousuf Lone, who was killed by unknown gunmen, on May 18, 2017. (FPK Photo/Vikar Syed)

But whatever was conspired, he says, was conspired in the dead of the night. No one saw it, he says. “So holding anyone responsible is difficult.” But yes, two days before his killing, he continues, police’s Special Operations Group (SOG) and army’s Rastriya Rifles (RR) raided their house.

The joint force known to act on a tip-off had come looking for him at around 2 in the night, he says. After finding him missing, they left. “In fact, two days prior to his killing, my brother—as he told us—was summoned by police…”

Lone had a past. In 2000, he was first picked up by the forces from a marriage party and released after four years. “Then in 2010, SOG men from Srinagar’s Cargo fired and damaged his arm,” says Ahad, as the suspense looms large in the room packed with bewildered kin of the slain Lone.

After intermittent silence, Ahad talks about the townspeople—who initially termed the killing as the militant handiwork. But once militants showed up at his funeral to offer the gun salute, the mood changed. Similar scenes ensued on the third day of his killing, when some masked men appeared to retrigger the gun-salute. “I don’t know what to make of it,” Ahad spares his last remark before his nephew walks inside.

Now, the nephew begins detailing the mysterious death. Even he weighs his words carefully, “Eais chi hasasas mein, ye ma gow garri” (We are oblivious of the facts, since it didn’t happen in our home).

After a certain point in his conversation, he turns descriptive, like an incisive professor who leaves nothing unsaid: “It’s not as if someone, say an army man, caught hold of him—and next day, we found his dead body. What happened in the dead of the night… who knows? They [army] say we didn’t do it. They [militants] say we didn’t do it. Teli kem kaur? (Then, who did it?) Eais chi baybas, ain (we are helpless, blind).”

It’s the politicians, he says, who feed the children with thoughts, like we are different and that ours is the political problem and keep the pot boiling. And then, he says, the same leaders land our kids in the trouble.

“Sean Mahboobaji draye yi wanaan wanaan ki yeh chu siayasi issue (Mehbooba told us that it’s a political problem),” he says, rather dismissively. “Omar saeb ti draav yi wanan wanan (Even Omar said the same thing).” But these politicians, he says, only rant about their Self Rule and Autonomy. “Actually, they are the ones who make us to bear the brunt,” he says. “Yeman masssom bachan chuni khatah (These kid protesters aren’t at fault).”

Javed, the nephew, says nobody ever told them what this Agenda for Alliance is, and yet some sections are hell-bent, linking their rage with it. “I am an illiterate,” he says, “so are many others here. Nobody has ever told us what all this means.” The reality, he says, is that the unarmed Kashmiris—“sandwiched between India, Pakistan and China”—are dying. “Asi codukh gretni hund auth” (We have been sandwiched).

“China is occupying a portion of our land, too. We are helpless. Both forces and rebels are armed. We are in the middle. Anz manz moeud Kashir (In the end, these are Kashmiris who die).”

Amid this political projection, this 50 something man says, Kashmiris have lost the capacity to think. “As per my experience, we don’t know anything and have lost the capacity to comprehend things around us,” he says. “The only visible thing to us is death. People are dying, and women and children are being left behind. This is our reality.”

Pointing towards the bewildered children of the slain Lone, the nephew says, “yiman kus khudayyi kari dastegeeri wyen?” (Who is going to take care of them?)

Clearly, whenever the anonymous gun kills in Kashmir, more questions trail than their answers. Such killings create a cycle of suspicion around. And perhaps being mindful of the perils involved, the slain’s family remains tight-lipped. In fact, the recent spate of political killings in southern part of Kashmir revived the nightmare of the turbulent nineties—when the politically ‘affiliated’ men were bled to death.

Pulwama’s “Vakil Sahab” was the latest addition in it.

In his forlorn home, the visibly mournful family members are going about their reluctant routine. They may not appear bewildered like the Lone family in the same province, but they evidently are clueless over the obvious query: who killed advocate Abdul Gani Dar? Dar, their father, was PDP’s district president.

His widow Mehbooba sits quiet and blank in one corner of her room. The moment, the apparent question—“who?”—follows, she pensively replies, “You should ask the cops, who were accompanying him at the time of his attack.”

On the day of his killing, she says, Vakil Sahab, as he was known in the area, was on the way to Srinagar for Shab-Guazari, night long prayers, at the Hazratbal shrine.

“I had to visit the city, too,” she says. “We would have gone together but he had some work at the court in Pulwama. So he told me to move.”

Mehbooba reached Srinagar and received a call that Dar has been attacked. “I was planning to rush back but received another call that he has been referred to Srinagar. In the meantime, my son also reached the hospital,” she recalls. “When we both reached there, he had already succumbed to his injuries.”

Dar was attacked in Pahoo area of Pulwama on April 24, when his car was intercepted by “unknown gunmen”. Police did “identify” his assassins, but the family insists that they will never know who the culprits were.

“Police identified them within 24 hours,” Mehbooba says. To which, her son Owais intervenes, “But we don’t know. It’s the police who are saying that they have done it.”

If the incident would have taken place in the house or outside, she continues, we would have shared full details. “Or if someone was accompanying him on his way that day, then we might have been able to confirm anything.”

Mehbooba says that to kill a man of his character and standing is strange. “You can go out in the market and ask anyone, who he was. He was a pious man. He hasn’t harmed anyone in the area,” she says. “I have no doubt in mind when I say that Vakil Sahab was a Mard-e-Momin (pious man).”

After his killing, chief minister Mehbooba Mufti and finance minister Haseeb Drabu were scheduled to visit Dar’s home. However, Mehbooba, Dar’s widow, told them to stay away — as the situation wasn’t feasible for such a visit. “They were coming. Security was beefed up in the area. I called them and told them not to come. What if somebody threw a stone at them or something else had happened? That would have resulted in more trouble.”

Notably, the situation in the CM’s backyard, south Kashmir, is so out of hand, that Dar’s condolence meet was held in Jammu.

But as the widow grapples with her irreparable loss, she becomes livid over the possibility of bringing the perpetrators of her husband’s killing to the books.

“Even if the government kills those killers in front of us,” she pauses to ask, “will he (Dar) come back?”