Anantnag: A short mud trail leads to an old house in Breenth, a village some six kilometres away from the town of Anantnag, one of the four districts constituting the volatile South of Kashmir. Before one reaches the house surrounded by thick lush vegetation, one could hear the cries of women breaking the deep silence of this idyllic village. They were no elegies or songs of grief. Only the chant “Azadi” rose from the house as females came to offer their tributes to the survivors of yet another “martyr”.

The house had lost one of its members, but it was unlike a place of mourning. Here there were no wails or the beating of chests. The visitors had come on foot, and in hired lorries to the house of slain Tahira – a wife, a mother of three and a hardworking homemaker – shot dead by forces on July 01, 2017.

Women going to Tahira’s house in Breenth Anantnag to pay their tributes. (FPK Photo/Moosa Hayat)

Early morning of the last day of her life, Tahira, in her mid-40s, had been startled by an announcement from the local mosque. “There is an encounter going on near the stream, militants have been trapped,” said an impassioned voice.

She rushed out, telling her husband, Abdul Rashid Chopan, that she would “take a look”. Zahid, 20, her eldest son too had gone out a few minutes before Tahira. Her other two kids – son Imran, 18, and daughter Mehak, 12 – were far-away at their relatives’ places. Around 10 minutes later, Rashid heard some gunshots.

“From my instincts, I felt something bad had happened, I rushed out toward the road and found some people hurriedly bringing along Tahira, she had been shot,” said Rashid, a gardener.

Rashid’s world had tipped over too fast, leaving him no time to realise the immense loss he was about to face. Here was his wife, a partner of over two decades, lying almost lifeless in his arms, blood oozing out from her. Rashid, along with a few other people, rushed her to the district hospital near Jangalat Mandi. The six kilometres drive to it, however, was too long a journey for Tahira to sustain. She died on the way.

Explaining the entry and exit wounds her wife sustained, Rashid took his arm behind his back.

“She was shot here (pointing at his right flank) and the bullet pierced through her heart,” he said with an imminent tiredness in his voice and eyes. As Rashid described the fateful day, Imran, his younger son, rushed into the room.

Clad in black Khan Dress and a skull cap, this teen had an air of stony silence to him. Not unnatural for a youth whose mother had been killed to feel and act so.

“He [Imran] could not attend the funeral, he was far away in Wadwan village at his relatives,” his father said. Soon after completing Class 8 in a local government school, Imran had joined Darul Uloom Simnaniya, a local religious seminary to learn the Holy Qur’an by heart. His younger sister, Mehak, too had preferred an Islamic education over the formal one.

“Her mother wanted her to take up the Islamic studies,” Chopan said about Mehak, who remained silent all along, her face partly covered with a scarf.

While Rashid spoke, Zahid, the eldest son in the family, a tall lanky guy, left to write his Class 10 English paper.

The silence, the disarray among the Chopans was conspicuous. They had lost an important member, one of the two bonds holding all of them together, but they were not mourning.

“I don’t know what will I do without her, she was the sole caretaker of the home, the barn and the fields. I used to be at work; back home she took care of everything. I know what I have lost but I am not mourning for she died a noble death,” said Rashid.

“We had promised each other that if any of us die, the other would not remarry for the sake of the kids, I will keep that promise,” he added.

Tahira had been killed near the encounter site, around 800 metres away from her house. Imran was our guide to it. He took us to the exact point where his mother had been shot, a stone’s throw away from the bombarded house. A stream gushed parallel to the walkway to it, which still carried the marks of huge tyres made after gigantic army vehicles flattened the mud beneath.

“The Casper vehicles made those marks,” he said.

Kids look at the razed remnants of the house in Breenth, Anantnag where Bashir Lashkari and his aide were trapped and killed by the forces on July 1. (FPK Photo/Moosa Hayat)

Casper vehicles are army’s latest addition to carriage vehicles in Kashmir. An impenetrable iron casket on four gigantic wheels, seemingly designed to petrify.

The walkway to the encounter site was too narrow and muddy for even a light motor vehicle to pass through but not for a Casper. It had forced its way through as suggested the trampled sideways.

Forces personnel, which locals claim were at least twenty thousand in number, had cordoned off an isolated single-storey house where Bashir Ahmad Wani aka Bashir Lashkari or Abu Ukasha, the Divisional Commander of militant outfit Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), and Abu Maa’az, his non-local associate were trapped a little before the dawn of July 1.

The house belonged to one Bashir Ahmad Ganie. The family, of at least 12 members including a few kids, was in the house when the encounter began. At the same time, local men, women and teenagers were trying to intervene. They resisted the forces personnel by raising slogans and coming near the besieged house.

The devastated interiors of the house where the encounter took place. (FPK Photo/Moosa Hayat)

In retaliation, Tahira was the first civilian to be shot. A few hours later, another youth Tariq Ahmad Chopan of the nearby Dahrun village also succumbed to his injuries. At least two others were hit by bullets but survived.

Huge contingents of Army and policemen had cordoned-off the place cocooned by walnut trees on one side and willow trees on another.

For around seven hours until noon of July 01, the family refused to come out and give up on their “guests”.

“They were warned several times by the Army, but it was only after the militants urged them to go out that they came out, and then the house was bombarded by mortar shells dropped from a helicopter while troopers on ground kept on firing thousands of rounds at it,” said a local who was sitting on a pile of bricks, the remnants of the house in which the militants were trapped.

The Ganies had moved in only a year ago. Before the house faced hell-fire, it would have been a typical villager’s abode: a barn facing it, a gushing stream on its left and a huge orchard surrounding it. What was left now were the partly-burnt trees, the devastated barn, the hanging ceiling and the huge bullet marks on it, all sketching the destruction it faced. The scattered bricks thrown around 60 metres away from the house explained the impact of the mortars fired at it.

The remnants of the Ganaie’s house where Bashir Lashkari and his aide were killed. (FPK Photo/Moosa Hayat)

The family had now taken shelter at their relatives’, who lived at a walking distance. The villagers had already started pooling money to help the Ganies rebuild their place. A trail of locals kept on visiting the site.

“I myself counted 74 forces vehicles on the approach road to this house, they stealthily had surrounded the whole area,” said one of the locals.

“The family was refusing to come out, they were saying they will prefer to die along with the militants.”

Another visitor to the wretched house suggested us to visit the family of Tariq Ahmad, the other civilian killed during the gunfight.

“They are very poor, Tariq was the only earning hand in the family, they live in the nearby Dahrun village,” he said.

Dahrun was around five kilometres away from Breenth. A motor-bike ride on a curved road cutting through the densely green area made us stop a few times to ask for the exact location. The people knew it very well and accurately guided.

For a first-time visitor, the silence around the roads, the open shops, the passersby, and the scintillating background of hillocks would make this place one peaceful scenic spot. That was until we reached a point where a grave veiled in green flag faced us. Freshly dug, it had been adorned by flowers.

“That is Shaheed Tariq’s grave,” said a teen sitting opposite to it on a closed shop’s porch. We had halted at the right place.

Opposite to it, a trail of white plaster powder marked a curvy by-lane guiding visitors to Tariq’s house.

The family lived in abject poverty, so much so that they did not have ample space to receive the visitors. Their next door neighbour had brought down the wall separating the two houses to let his compound and house open for the people visiting to pay their tributes to another “martyr”.

A carpenter by profession, Tariq, 21, also used to rent out ponies to make some extra money during the Amarnath yatra season to cover the treatment cost for his father, Mohammad Rustum Chopan, who suffers from Blood Cancer for a few years now.

On the day he was killed, Tariq had left home early morning to reach Pahalgam. He had to cross through Breenth to reach his destination. At around 7:30 am, the family came to know that he had been shot. “He was hit by a bullet in the left side of his lower abdomen. The bullet had ripped through his body only to exit from one of his cheeks,” his cousin said.

Tariq, given the nature of his fatal injury, must have been ducking for cover when he was shot. He, as per the family members, was immediately rushed to the Srinagar’s SKIMS hospital.

“The boys who accompanied Tariq were stopped near Sangam by Army personnel. They were beaten to pulp. One of them had jumped on dying Tariq to save him from batons. The time lost was crucial, Tariq succumbed as soon as they reached to the hospital,” said one of Tariq’s relatives.

Tariq’s body had been kept at Srinagar’s Police Control Room and only handed over to the family in the evening to avoid or at least lessen the attendance of people at his funeral. But that didn’t happen. Thousands poured in to take a last glimpse of the ‘hero’ Tariq’s death had turned him into.

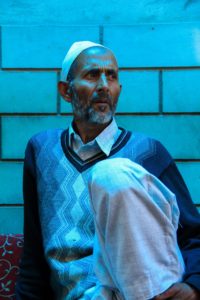

Back home, his weak and pale-faced father was hardly speaking. Already living a torrid life, he must have been shattered by his son’s death.

Slain Tariq’s father, Mohammad Rustum Chopan, who suffers from Blood Cancer. (FPK Photo/Moosa Hayat)

“He was the only working hand in the family, he gave six pints of his blood to me when I was being treated for cancer, he had turned all pale and white for me,” the only words the old man uttered.

Tariq’s elder brother Ashraf was left almost disabled after being tortured by forces in 2016.

“He (Ashraf) was working in the fields while the forces chased the protesting youth. While they all managed to flee, Ashraf became a soft-target for the forces, who took him away, only to release him almost a month after, his limbs broken,” said the neighbour who had offered his space to accommodate the visitors.

Shahid, 11, the youngest of the three siblings, was still in school.

In a canvassed tent put up in the neighbour’s yard, a bunch of women surrounded Tariq’s mother: A frail and old lady whose sunken eyes and dejected face tore through the silence that had engulfed her. We couldn’t muster the courage to ask her anything or to console her. Here again, we heard no elegies or wails but only a chattiness in the air about Tariq and his glorious “martyrdom”.

Among those paying tributes was Azad Rashid, a youth of Soaf Shali, Kokernag, the home-village of the slain LeT Commander Bashir Lashkari.

As visitors prepared to leave, Azad gathered everyone for a round of prayers for the deceased.

He agreed to accompany us to his village, which was around 15 kilometres away from where we were. It was a smooth trip on a macadamised road laid out in the most beautiful natural setting one can imagine. Green, vast fields, decked by hillocks and streams, made us cover the journey in no time. On the way, Azad would point out various villages whose youth had been “martyred” in last year’s uprising.

At Hangulgund, near Kokernag, we had to take a left to traverse in around 2 kilometres. And there it was, SoafShali, the “village of martyrs” as Azad termed it. The small patch of land in front of the Central Masjid of the village was dotted with a few graves. The freshest one was of Bashir’s, as was revealed by the large signboard carrying his photo in camouflage while holding a gun.

Bashir Ahmad Wani’s (Bashir Lashkari) grave at his native village Soaf Shali. (FPK Photo/Moosa Hayat)

An Urdu couplet on it read: “Zameer Lala mein roshan chirag aarizoo karday, chaman kay zarray zarray ko shaheed justujoo karday(Lit the flame of wishes in the conscience, let every inch of this land crave for martyrs). Beneath it read: “Shaheed Bashir Ahmad Wani a.k.a Akusha bhai, martyrdom on July 01, 2017.”

Bashir had been laid to rest close to his home. A torrid, non-motorable road led to an old house built by Bashir’s grandfather. The low-ceiling, the narrow and muddy staircase, or the small rooms separated by rodent-eaten wooden walls: nothing of it seemed of this century.

Bashir’s “fame” had crossed boundaries the way he did when he first decided to be a militant in 1999. The flurry of visitors at his home continued even five days after his death. People had been flocking in from different parts of the valley. Some had even come from Jammu to pay their tributes.

Bashir’s younger brother Mudasir and his old uncle were the only people left in the house now. Bashir’s parents had passed away when he was a kid.

Mudasir claimed how his brother was “forced” to return to the path of militancy he had long given up, and was even jailed for, for years.

“He suffered immensely, first in the various jails outside Kashmir, and then when he was released, at the hands of several police officers. For years, he was continuously tortured both physically and mentally to the extent that he thought it was better for him to pick up the gun again,” said Mudasir.

Knowing that he may not survive the encounter with the forces, Bashir, on the morning of July 01, had made the only call to his brother since he had rejoined militancy in 2014.

“He said that he and his other aide were trapped. He was not panicked at all and told us that he was happy that he was on a fast and was about to achieve the martyrdom he always longed for,” said Mudasir with a resolute tone defying that of a person who had lost his sibling.

“God Willing, I will break my fast in Jannah,” Bashir, as per Mudasir, had told him before hanging up.

“There is no mourning in this house, we are rejoicing his martyrdom. The whole Kashmir is proud of this son of the soil,” Mudasir added.

Bashir’s funeral, as per one of his neighbours, was attended by hundreds of thousands of people. There were multiple rounds of prayers to accommodate huge rush of visitors, many of whom had travelled all the way from Kishtwar and Jammu to take the last glimpse of Bashir.

“Thousands more had to turn away because the security forces had placed curbs on all the roads leading to our village,” the neighbour said.

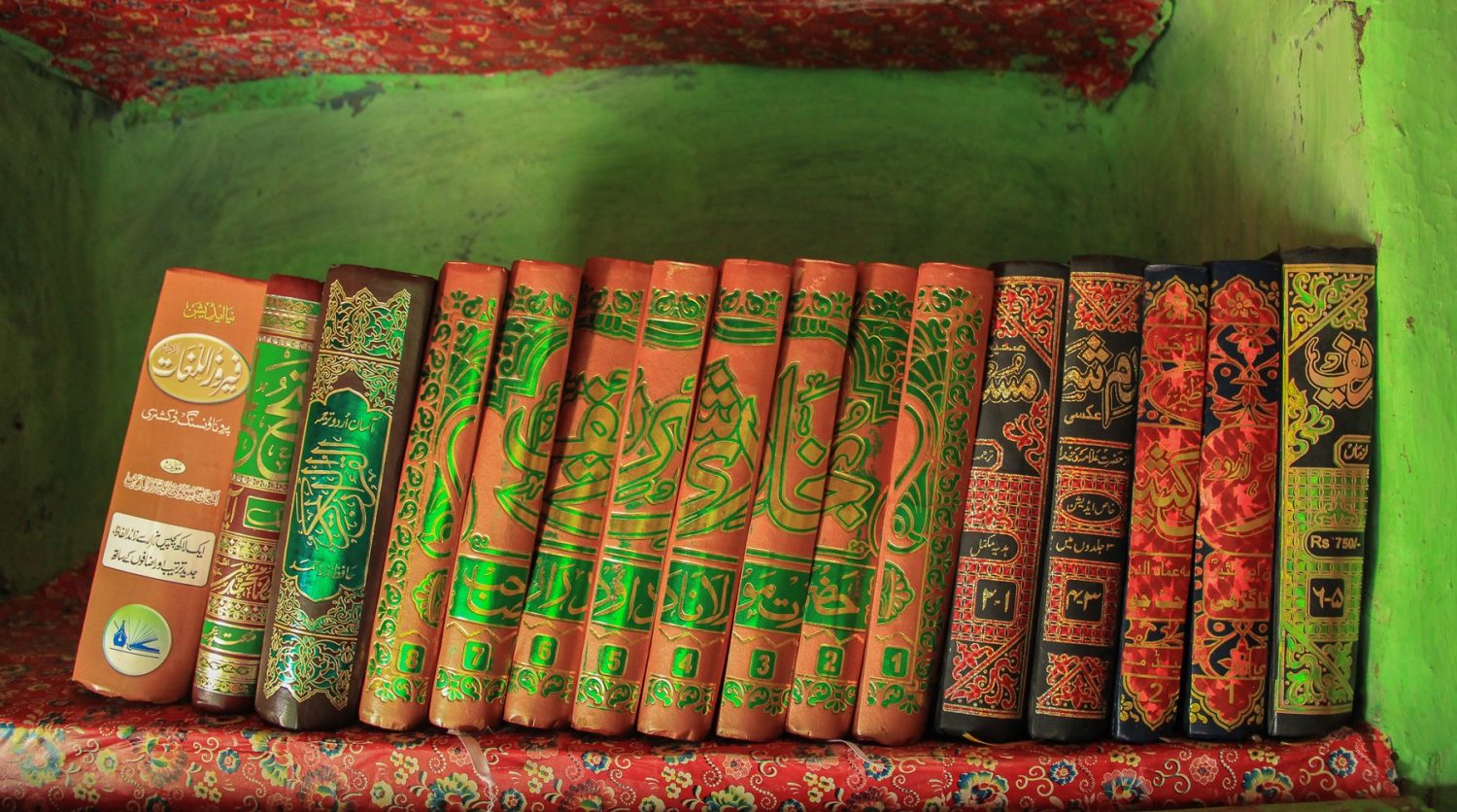

The small room where visitors had huddled together had a few posters pasted on its withered walls. They carried verses of the Holy Qur’an and sayings of the Prophet (PBUH) neatly written in Urdu by Bashir himself during his days of incarceration.

A bunch of Islamic books were neatly kept in a row on one of its shelves. As per Mudasir, all Bashir ever owned were these books.

“He had bought them out of his jail savings which were a meager Rs 10 a day,” he said.

A bunch of Islamic books Bashir had bought from his savings in jail. (FPK Photo/Moosa Hayat)

During the course of this interaction visitors kept on coming and leaving. The neighbours were busy in serving them sweetened water followed by tea and bakerkhanis(a crispy muffin specific to Kashmir). We too had to cover around 80 kilometres to reach back to Srinagar. The highway between Anantnag and Srinagarwas swarmed with army personnel. At many junctures, the forces were compelling the civilian motorists to allow the massive convoys pass through while the rest of the traffic remained clogged. Anyone refusing to give way faced batons and abuses.

“That is how they treat us in our own land,” we heard a woman shout as some forces personnel had stopped a mini-bus on the highway and marched down its passengers including the females.The civilian driver, it seemed, had resisted to give way to the approaching army vehicle.