Kashmir police chief flanked by allied forces’ top bosses recently made a surrender offer to insurgents in a joint presser. But if the track-record of the surrender policy executed by state agencies since mid-90s is any parameter, then the offer seems only an extension of the old policy paralysis.

As a ragtag street fighter, Showkat Wani was once a loaded gun — surfacing from the narrow alleys in downtown to drop bombs on pickets and patrols. Then he lost his mentor—the notoriously famous Dasti Boutal—the boy-faced Bohri Kadal insurgent known to engage forces in no-brainer battles inside the labyrinth of Old City during nineties. But as the war consumed most of his comrades, Wani left tongues wagging in 1998 when he suddenly surfaced in the group of ex-militants to throng a bank.

Before anybody could guess, Wani—a burly middle-aged man with a big scar (a reminder of his rebellious past) on his left cheek—had shown up at the bank to avail the Dr Farooq Abdullah-led government’s State Employment Scheme for surrendered militants. For giving up rebellion, the Farooq government wanted to establish micro/small units for the surrendered militants.

Inside his Zainakadal house that vibrates as vehicles zoom down on the street, Wani shows a copy of that cabinet order vide No.96/10 of April 24, 1997 in which a job with full dignity was promised to the erstwhile rebels. “Most of us became surrendered militants for a reason,” says Wani, sitting against a paint-peeling wall.

“We did it for survival — because in an unequal war, we were being badly butchered.”

He might have a reason, but the conflict zone is known to carry its own rulebook. It doesn’t make it a pushover for anyone. And even before Wani could know it, most in his weapon less camp had become expendables.

The first underhand sign appeared when the banks in Kashmir refused to implement the Farooq Abdullah government’s ambitious employment scheme. They cited their fear of loan recovery.

For the war-weary Wani, the move was a clear snub. At once, he was reminded of the grilling he faced inside the joint interrogation centre for two months after surrendering along with his two comrades. He became a police station regular, felt hounded, but stayed patient — perhaps good times were just round the corner.

But when it all proved to be a big hoax, he decided to resign himself to his unsure fate. By then, he was already facing occasional taunts from locals for “betraying the movement”. He turned taciturn with turn of the new century. But the hounding never stopped. In wake of any ‘law and order’ trouble in his area, he was asked to report.

“I could sense men stalking me most of the times,” says Wani, flashing a frozen look at his window opening into a rusty Old City view. “Being a surrendered militant was indeed a historic blunder.”

In 2010, Wani bumped into his former comrades inside a police station where he was called to fill a form. That year, the police agencies had issued profiling forms three times, asking the former rebels to fill the various details including expertise and use of weapons, bank and property details. Many termed the Omar Abdullah government’s decision as a bizarre attempt to force around “30,000 ex-militants” to work with police agencies.

Years ago, as coming events cast their shadows, some in Wani’s beleaguered group had realised how they had become toys in the games based on a certain policy. One of the enforcers of that policy is now enjoying his retirement period in Srinagar’s plush neighbourhood, Hyderpora.

The unforthcoming counterinsurgent of yore is now penning a book. As a “conscience-keeper” now, he wants to write about the period when the State used the surrender policy as an effective counterinsurgency tool to cut militancy to size. “Not many understood it then,” the former cop says, “as to how that army of surrendered militants were raised to go after against their own unbending comrades.”

Inside his smoke-filled room, he mentions Budgam’s ‘Panther’. Before becoming an army asset, ‘Panther’ was JKLF’s area commander and ironically, on the army’s hit-list. “No sooner did he surrender,” says the ex-cop, taking a long drag of his Marlboro Cigarette, “he helped the army to gun down his own former comrades.” Then on Kashmir’s theatre of war, the ‘Panther’-like characters were known to make surprise appearances.

Many such characters cropped up after the then Governor KV Krishna Rao formally announced a “surrender policy” in August 1995. In the first month itself, some 111 militants turned up with weapons. They surrendered on assurances of being allowed to rejoin their families. As part of “mainstreaming”, the State wanted to make drivers, welders and mechanics out of these former rebels inside Reasi’s rehabilitation centre. But the ‘powerful’ garrisons had some other plans.

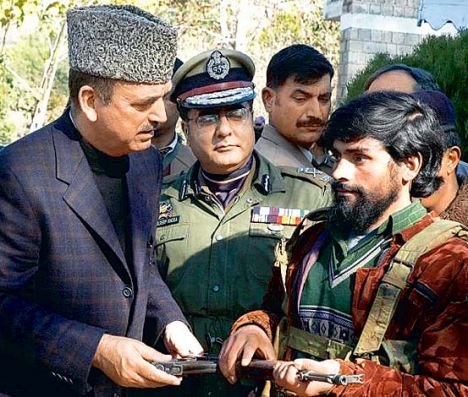

Former Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir Ghulam Nabi Azad during a surrendering ceremony at Ramban in 2007.

“They wanted to use these surrendered militants as centrepiece of the anti-insurgency ops for a monthly dole of Rs 1500,” the retired counterinsurgent says. As combat ops protracted, he says, these surrender militants did act as per the military script: busting militant bases, killing battle-hardened Afghan Mujahedeen in the Chenab Valley and helping catch insurgents as a part of Special Operation Groups.

After a certain point in the mid-90s, these surrendered militants were caught in the BSF versus Army surrender competition. Surrendering before one would invite them the other’s wrath, thus forcing them to surrender twice, the retired cop says.

Amid this apparent tad race for awards and rewards, the militant outfits would be baying for their “treacherous” blood. Sensing a looming threat, the then adviser (home) Lt-General (retd) DD Saklani promised them to allot 12-bore guns. It proved another hoax, forcing the beleaguered group, amid mounting insurgent attacks on them, to request to buy the promised 12-bore guns themselves. The request was turned down, making many repentant of their act.

It’s this historic betrayal that makes many surrendered militants to scoff at the fresh surrender offer, coming 24 hours after the forces motivated an insurgent into surrender—for the first time during a gunfight in several years—in Shopian’s Barbugh area on Sep 10, 2017.

A day after, the joint force of police, army and CRPF sat together inside the Police Control Room to address a presser. “There were all the reasons to knock him down,” said IGP Munir Khan, expressing ire through his big, cold eyes. “But we didn’t.” He took what looked like a calculative pause to continue: “That is the difference between us and terrorists.”

Then a wave of disturbance ensued in the room. A masked cop entered with a “surrendered” insurgent, Adil Hussain Dar. While two of his comrades—Altaf Ahmad Rather and Tariq Ahmad Bhat—were gunned down, Adil was forced to drop his gun.

“There was every reason to kill him,” Khan repeated, taking a good look at four-month-old insurgent Adil, before offering him to talk to media.

The calm-faced—and somewhat stunned—captive insurgent nonchalantly denied the talk offer. Khan patted on his cheek like a big daddy before his men took him out.

Khan again emphasized how the counter-insurgents are good at offering an option of surrender—“unlike militants who hit our men during vacations or playing volleyball.” After the rebel, a rebel-in-making—OGW, described as “militants without weapons” by Khan—was paraded.

“Our target remains the militant leadership to stop recruitment,” he said, before letting GOC Victor Force BS Raju to talk about the surrender policy. “We can arrange free passage for militants,” GOC made it short.

Raju talked about the surrender policy at a time when the army is conducting its K-Ops based on the Op All-Out—“a blueprint to deliver a lethal blow” to Kashmir insurgency. Through a secret district-wise survey, prime locations of 258 militants have been reportedly mapped.

IGP Munir Khan (left) and GOC Victor Force BS Raju during a joint presser.

Amid all this, the renewed surrender policy has raised questions: Who is going to surrender, to whom, and for what?

Many read CM Mehbooba Mufti’s plea—“bring the local militants home”—behind the fresh surrender offers. But she is facing an in-house grumble from BJP on this, like on other issues. The rightwing outfit terms the surrender policy as “a grave threat to the national security”.

It’s in this backdrop that Wani sees the reincarnation of old demons that continue to hound him years after he became a surrendered militant.

Just outside his home, Old City is reeling under another phase of restrictions. The lanes, now thickened with helmeted and padded cops, were once Wani’s combat zone where he would fight a war of attrition against Indian State. That war has now spread far and wide, throwing new characters and new possibilities. Even then, somebody like Wani sees his own past in the freshly made surrender offers.