As the world is observing the 39th anniversary of the Iranian Revolution, many in Kashmir are recounting the preparations to host the exiled leader in the Valley at the peak of the revolution. Although the fall of the Persian monarchy derailed Ayatollah Khomeini’s Kashmir visit, but his revolution sparked many things in Valley where some historians trace his family roots.

When a French journalist in an interview asked Ayatollah Khomeini where he would go if the French government revoked his asylum, he had said, “I would prefer going to Kashmir as I have received an invitation from Aga Syed Yusuf during my time of exile in Iraq,” as mentioned in a book Tajalliyat written by Aga Syed Baqir of Budgam.

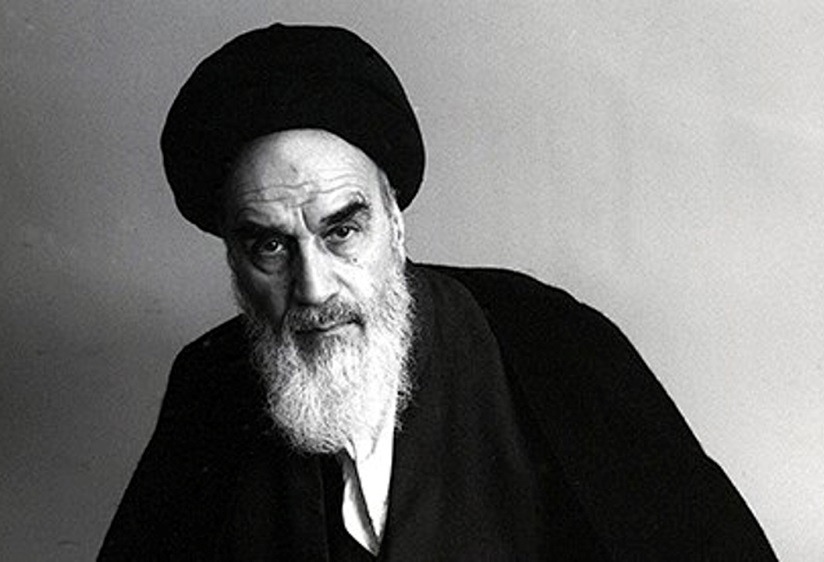

In 1978, at the age of 78, when in Neauphle-le-Château, in a house that had been rented for him by Iranian exiles in France, in a suburb of Paris, Khomeini gave hundreds of interviews (around 130) in the four-month time that he spent there. This marked the ending days of his 15-year exile from Iran by the then Persian monarch, Mohammad Reza Pehlavi.

At this point, Khomeini had been recognized worldwide because of his hard-line opposition to the Shah’s regime.

In France, he got the international press coverage that he hadn’t been able to achieve in Iraq or Iran. Hundreds of journalists from all over the world thronged to a suburb of Paris where the biggest stories before Khomeini’s arrival had been car accidents and weather reports. He was named the ‘Man of the Year’ in 1979 by American news magazine Time for his international influence, and described as the “virtual face of Shia Islam in Western popular culture”.

During the last few months of his exile, Khomeini received a constant stream of reporters, supporters, and notables, eager to hear the spiritual leader of the revolution. The word of Khomeini’s possible Kashmir ancestry in Reza’s statements spread worldwide and soon, several parts of India emerged with claims of the cleric’s ancestry.

Earlier, during his time of exile in Iraq’s holy city of Najaf for more than a decade, Khomeini and Aga Syed Yusuf of Kashmir used to exchange letters and telegrams often. The exchange of letters was rather frequent till Khomeini was exiled from Iraq in 1978 by the then Vice-president Saddam Hussein on the request of the monarch, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, of Iran.

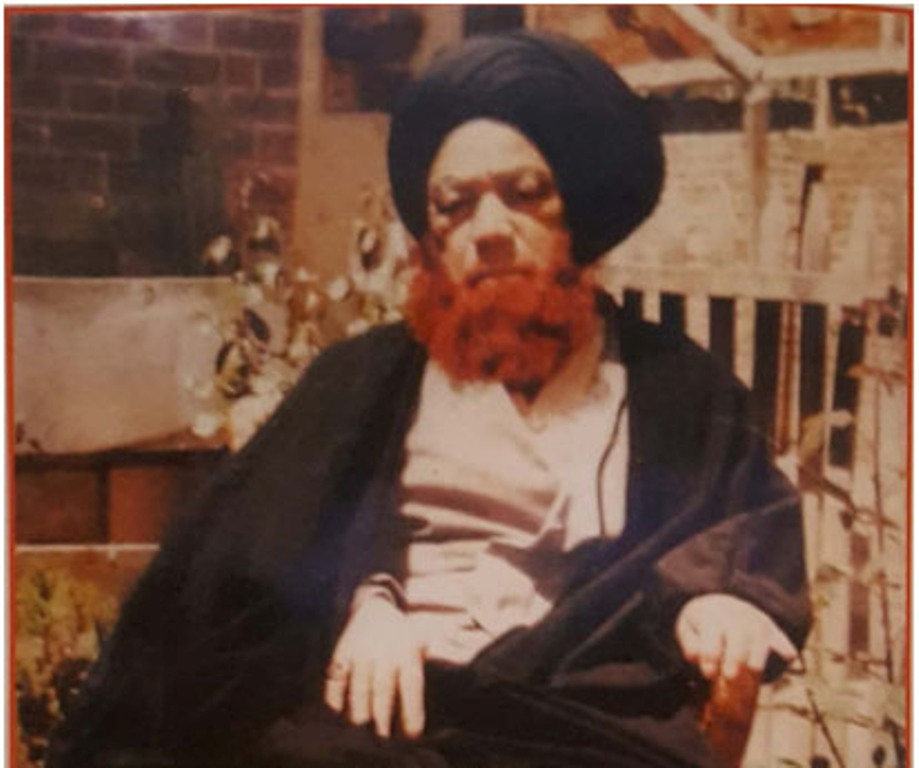

Aga Syed Yusuf

In Iraq, while Khomeini was still in correspondence with Aga Syed Yusuf, and learned that the things were getting sensitive for the Imam, he had sent him an invite to visit Kashmir through his late son Fazlullah who then studied in a religious seminary in Najaf. He was entrusted with the task of handing over Aga’s letter to Ayatollah Khomeini. Khomeini was told in the letter that he would be looked after by the family and would be very welcome in the hospitable air of the vale of Kashmir.

When Khomeini’s reply came, it was a letter of gratitude and appreciation, while also politely declining the invitation. There was a lot going on that he must attend to, he had said.

In the same letter, he did, however, mention in passing, that he would have loved to come to Kashmir as it was also his ‘ancestral land’.

According to a statement of Khomeini’s elder brother, Syed Morteza Pasandideh, Khomeini’s grandfather, Syed Ahmad, left Lucknow (his point of departure was Kashmir, not Lucknow) sometime in the middle of the nineteenth century on pilgrimage to the tomb of Hazrat ‘Ali in Najaf. While in Najaf, Syed Ahmad met Yousef Khan, a prominent citizen of Khomeyn. Accepting his invitation, he decided to settle in Khomeyn to assume the responsibility for the religious needs of its citizens and also took Yousef Khan’s daughter in marriage.

Syed Ahmad, by the time of his death, the date of which is unknown, had two children: a daughter by the name of Sahiba, and Syed Moustafa Hindi, born in 1885, the father of Khomeini. Syed Moustafa began his religious education in Esfahan and continued his advanced studies in Najaf and Samarra (this corresponded to a pattern of preliminary study in Iran followed by advanced study in the “Atabat”, the shrine cities of Iraq). After accomplishing his advanced studies he returned to Khomeyn, and then married with Hajar, mother of Rouhollah Khomeini.

In March 1903, Khomeini was just 5 months old when he lost his father. And in 1918, Khomeini lost both his aunt, Sahiba, and his mother, Hajar. Responsibility for the family then devolved on his eldest brother, Syed Mourteza, later to be known as Ayatollah Pasandideh.

Following the letter, during the uprising, there was word going on in Iran, and internationally, that Khomeini had Kashmiri roots. Aga Syed Baqir, in his book Tajalliyaat, writes that perhaps to delegitimise the revolution, Mohammed Reza Pehlavi, the Persian monarch of Iran at the time, emphasized on this to question the pedigree of the leader and wonder if his attempt at revolution was even justified or legal.

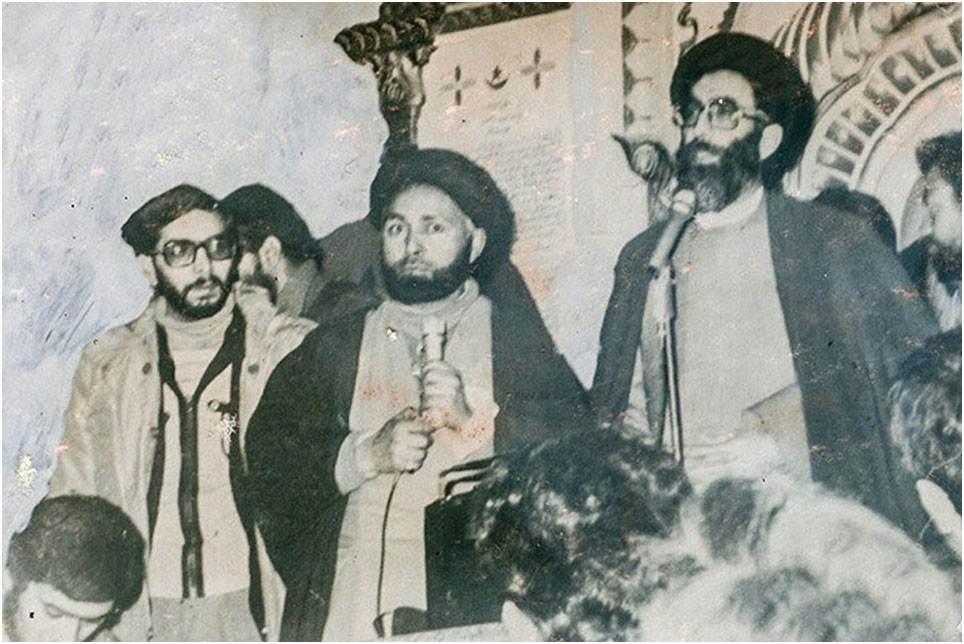

Aga Syed Baqir

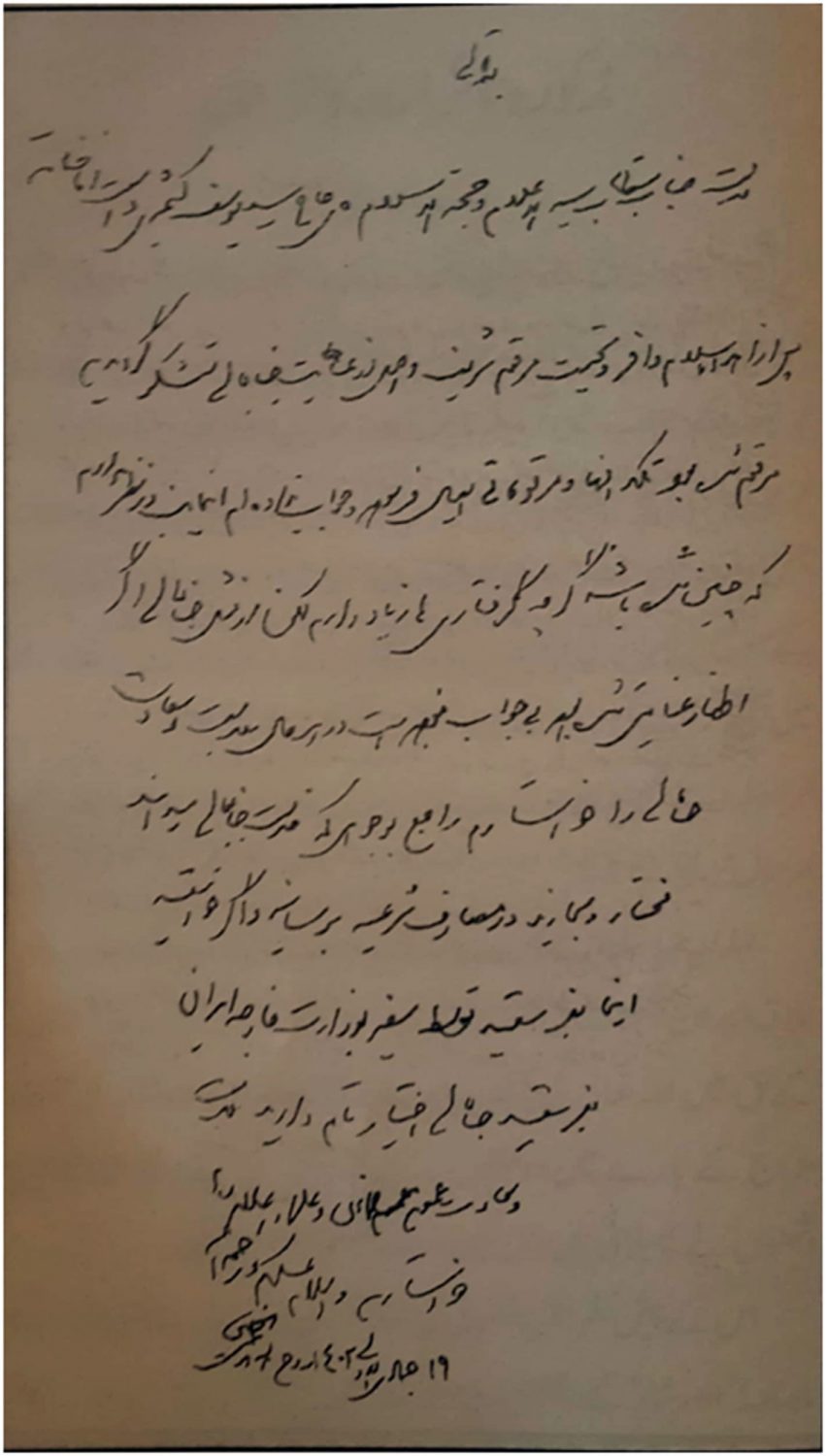

Amidst all this confusion and furore, Aga Yusuf wrote a letter to Khomeini asking him to elaborate on his Kashmir ancestry, so that he could do the genealogical ground work in Kashmir by consulting historians and genealogists and find out for sure about the Imam’s ancestral links to Kashmir.

In reply, Khomeini had said that “it was the popular belief here that his ancestor who migrated from Kashmir to Khomeyn was a man named Syed Ahmed and was sometimes called Syed Hindi, as one would call a man from Hindustan.”

“He came to Najaf from India or (then) Kashmir. From Najaf, he went to Khomeyn and settled there,” Khomeini had said.

This man, Syed Ahmed, was Khomeini’s grandfather. In his letter, he further asked the Kashmiri Aga if any ‘Syed Ahmed’ had left from Kashmir over a century earlier.

“In Khomeyn, it is said that he (Syed Ahmed) came from Kashmir. Sometimes it is also said that he came from India,” he had added.

In his book, Baqir claims that one of his ancestors had a brother whose named was Syed Ahmed, who fitted the description, and had travelled to Najaf through Lucknow and with whom, all contact was lost after his departure from Kashmir. He was declared Mafqood-al-Khabar, a legal term for someone who is lost, and of whom no information can be obtained.

When news was heard of Khomeini’s wish to go to Kashmir if denied asylum in France, everyone in the Aga’s family started thronging into action, calling for meetings about what and how the supreme leader should be welcomed. An invite party was to be sent to France to escort the Imam to Kashmir. Meanwhile in Iran, the Islamic revolution was gaining unprecedented momentum, the Shah of Iran was on his heels, time was running out fast, and the preparations for Khomeini’s arrival in Kashmir were taking time.

Khomeini had not been allowed to return to Iran during the Shah’s reign (as he had been in exile). On January 17, 1979, the Shah left the country, ostensibly “on vacation”, never to return. Two weeks later, on Thursday, February 1, 1979, Khomeini returned in triumph to Iran, welcomed by a joyous crowd estimated (by BBC) to be of up to five million people.

Kashmiris, though ‘happy about the success of the revolution in overthrowing the Persian monarchy’, were rather dejected that Khomeini couldn’t make his trip to Kashmir.

Baqir says in his book that Khomeini paid special attention to Kashmir after the success of the Islamic revolution in Iran, perhaps because ‘it was his ancestral land.’

Khomeini contacted Aga Yusuf frequently and there was a lot of cultural exchange. He would often call for the unity of Muslims all over the world.

“The visits, lectures, conferences from Iran enforcing Muslim brotherhood leave a trace even now,” writes Baqir.

These programs ‘aimed at the collaboration of Shia and Sunni school of thought’, used to draw huge crowds, who would be educated about the religious, political and cultural changes occurring in the newly emerged Islamic republic in the middle-east. Religious and cultural literature from Iran was frequently circulated in the valley in the form of books, pamphlets and magazines. Religious scholars, intellectuals, doctors, and political dignitaries from Iran used to come and travel though Kashmir at length, while also educating the population. These visits included dignitaries like Ayatollah Khamenei, Mohammed Raza Mehdavi, Dr Gulzada Gafoori and the most prominent among them being the current supreme leader of Iran, Khamenei himself.

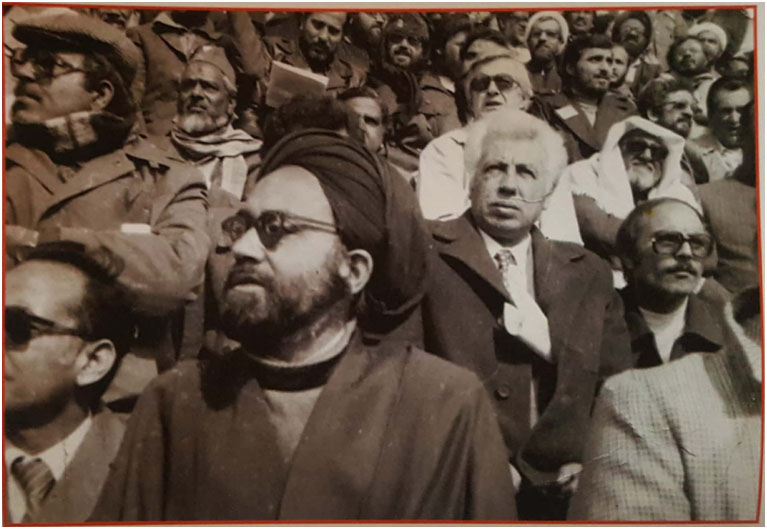

According to the late Qalbi Hussain Rizvi Kashmiri, an activist from Kashmir, in the year 1980 and during Sayyid Ali Hosseini Khamenei’s visit to Kashmir, he was there and has narrated ‘important’ memories from that trip.

“The Leader visited Kashmir in late 1980 or early 1981. The Leader also joined Sunni Friday prayers at the Jamia Masjd and prayed while standing before Mir-Vaez Maulawi Farouq and delivered a 15-minute speech there. The effects of this 15-minute speech on the history of Kashmir could be collected in tens of books and months of lectures. Throughout the history of Kashmir, it was the first time that a Shia cleric who was a global figure delivered a speech at a Sunni mosque,” writes Qalbi Hussain.

Sayyid Ali Hosseini Khamenei in Kashmir, delivering a lecture.

When Baqir was invited to Iran and met Khomeini at his house, he described his house as a modest compound with floor furnishing similar to the ‘wall-to-wall’ used in Kashmir, with a wooden Charpoy in the corner. During the conversation, Khomeini had asked Baqir about the situation in Kashmir and about his family.

In the months, probably years up to the visit, Yusuf had sent several letters to Khomeini, none of which had gotten a reply. Before leaving, Baqir was entrusted with a letter from Yusuf addressed to the leader. On meeting Baqir, Khomeini wrote what was perhaps his final letter to Aga Yusuf of Kashmir.

On March 30-31, a nationwide referendum resulted in a massive vote in favour of the establishment of an Islamic Republic. Ayatollah Khomeini proclaimed the next day, April 1, 1979, as the “first day of God’s government”. He obtained the title of “Imam” (highest religious rank in Shia). With the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran he became the Vali-e Faqeeh (Supreme Leader).

Like this story? Producing quality journalism costs. Make a Donation & help keep our work going.