This summer, an anthology of 12 essays was published and promised to provide fresh insights about the Kashmir situation through personal accounts and anecdotes. As the author argues in this review, the book brings both education as well as empathy to Kashmir’s story.

When young Mona Bhan visited her school after a long winter in 1990, she could feel that her classroom had become emptier. Faces had disappeared from her familiarity. They spoke to her of a community threatened into exile. But she did not merely gape at her pedestrian realities crumbling. Her younger self plunged into the world outside; one that resonated with the cries for liberation.

In the niches of the memory of life in the valley, even before the tempestuous 1990s, reigns a period startled with changes that stared at it in the face. Kashmir’s predicament was older than the historical newbies in the subcontinent. As life happened in continuous interludes, desolation started appearing vivid in the matrix of Kashmir’s peace.

Rage was fresh, new and captivating. One could hardly keep away.

In one such tide of turmoil, with the fall of Dhaka in 1971, young boys in Kashmir ventured out and shouted pro-Pakistan slogans. A young chap among them was slapped straight and dragged back home. This was journalist Zahir U Din being disciplined by his father.

On another scale of space and time, speeding through the City side of Srinagar that fascinated him, Mir Khalid chauffeured around his friends enchanted by the promise of possibilities. The stereo of his car roared with music that seemed to ring for him of a sense far above the antiquated views of Downtown Srinagar. But changes were soon going to break his speed into a moment wherein the dawn of conflict on his idyll was inescapable.

This was also the time when Cinema had been alive and breathing as a chimera of progress in Kashmir. Daata was one of the many movies that Shahnaz Bashir had enjoyed with his father as a child. Though, this was to be his last one at Regal Cinema – a memory from the past. Soon bunkers were built over frequented bridges. Things were changing exponentially.

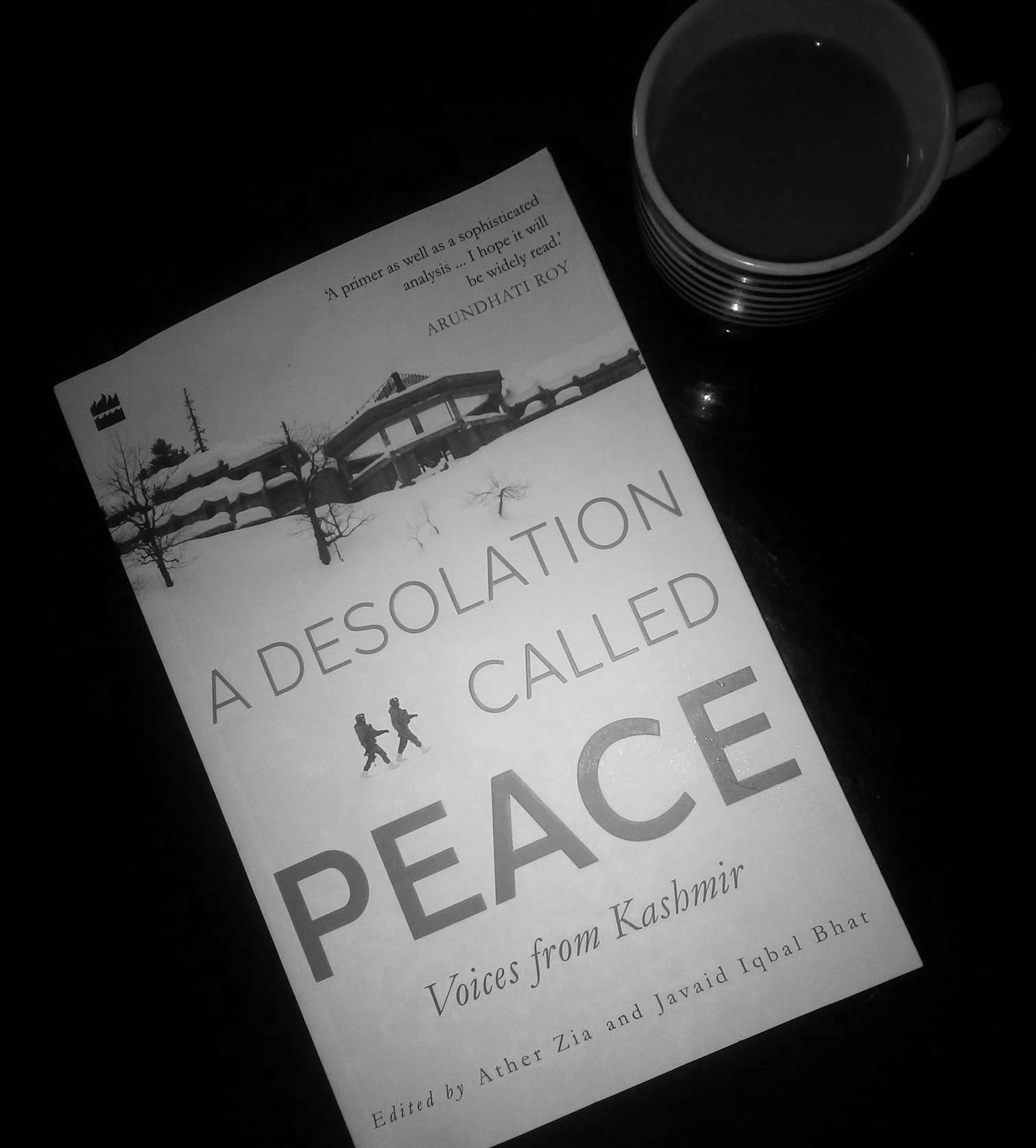

These stories emerge alongside many such accounts in a carefully curated collection of essays edited by Ather Zia and Javaid Iqbal Bhat. The twelve authors included bring a different flavour to each account by virtue of their distinctiveness. The editors have prefaced the anthology by an introduction that sets out to correct dominant historical (mis)constructions especially those that erroneously declare “beginnings” to serve a specific teleology (India vs. Pakistan) which benefits an anti-resistance historiography.

The twelve essays included in the book are all different in their textures yet loyal to a pro-Kashmir schema. Most of the essays deconstruct the notion of “peace” in Kashmir from 1947-1989.

“Voices”, the word in the title, meets us with a rather ordinary familiarity. But it is this cardinal word which exemplifies the significance of this work.

The book is an anthology of essays, which towers above the dryness and seriousness of diction that a generic classification as this would’ve typically invited. It owes its impact to the benefit we gift to personal anecdotes.

It appears as if the book travels and overhears different people recounting the political history of Kashmir through their personal accounts.

Sometimes, we travel through Downtown Srinagar and are stopped at Gaw Kadal by different pathways of memories. While Zahir U Din’s “Fragments from a Diary” has him walking from Sarai Bala to Gaw Kadal on 21st January; in Khurram Parvez’s memory it marked the day of his grandfather’s death in the Gaw Kadal Massacre. The alliterative remembrance of the Gaw Kadal Massacre is a device that unites all narratives.

Gaw Kadal bridge.

In “The Vernal Interlude 1989” by writer Mir Khalid we get a free ride from Srinagar’s Upper City Side to Safa Kadal, interspersed by a quotidian jump to Dublin which is employed to understand the becoming and unbecoming of various tides and colours of Kashmiri nationalism.

Each account has a streak of a “coming-of-age” narrative in a conflict zone.

Khurram Parvez recounts his journey from Kashmir’s reputed Burn Hall School, militarised precincts and vicinities towards a political consciousness that culminated into his tryst with APDP, JKCCS and AFAD.

Journalist Nawaz Gul Qanungo writes of Abdul Qadeer Dar’s venture into militancy and back.

Syed Zafar Mehdi’s essay recalls a feeling of “dubious distinctness” in him when he learnt that he was born during a curfew. However, he realises that unlike the midnight’s children of Rushdie’s universe, the uniqueness of being born during a curfew is ordinary in Kashmir.

Another consensus among the authors seems to be their explicit and in part, an implicit disavowal of Sher-e-Kashmir and his political idiosyncrasies.

Personal memories do not lend themselves to the hierarchies of privileging some lives over the others. We come across familiar and less familiar names – of family, friends and colleagues.

Mona Bhan’s grandfather, a Kashmiri (Pandit) who stood up for the Kashmir movement, had his politics draw a wedge in his personal life. He was dismissed and branded a “Pakistani Butta” (Hindu/Pandit) by his community. A term we hear less often, but must recall tirelessly to reiterate the contribution of Kashmiri Pandits.

Poet and activist Zareef Ahmad Zareef and anthropologist Mohammad Junaid enter to elucidate Kashmiri conflict through examining culture, especially literary. Zareef recalls the popularity of newspapers from Pakistan that were ‘consumed gluttonously’ in Kashmir. Through Akhtar Mohuiddin’s fiction, Mohammad Junaid devices a means of reinstating indigenous history of Kashmir.

The book does not stop at merely recollecting to reclaim narratives. At many parts, it conjoins the past to the present unconsciously. This gives the book a ring of a revolutionary manifesto. It isn’t achieved by any high pitched call for protest.

“…there was a relaxation in the curfew…”, recounts author Mirza Waheed; “There were blackouts… Nobody would put on the lights and if anyone even tried to, young boys would throw stones at that house,” recalls Khurram Parvez.

There are mentions of “student protests” and the much too familiar likes of it. These are trends that have repeated through decades. It is an awareness of this cyclic nature of repression and revolt that makes it a must read for the young and the new.

A Desolation Called Peace is a great read for anyone looking to strike an acquaintance with the Kashmir conflict. The introduction anchors the book well and aids the reader sufficiently. However, one does find oneself lurking at similar junctures a one-too-many times in the essays. Perhaps, another book traversing a lengthier timeline will be a significant leap.

Additionally, even as there seems to be an honest attempt to get all narratives on board, one does seem to yearn for more accounts from Muslim women in Kashmir. Similarly, even as there are accounts written and translated on behalf of people, one wonders if the same aid could be lent to those who seldom find a way to translate their experiences into the less accessible universe of the written and the published.

Nevertheless, the anthology’s mechanics of telling history through life stories constitutes an exemplary method of bringing education as well as empathy to Kashmir’s story.

Finally, the book’s unmistakable loyalty to the cause of Kashmir and Kashmiris makes it a must read. In times such as ours, in which, one often loses confidence in the destiny of Kashmir’s dissent – to remember and recollect is a radical act.

The reader of the book receives, as if in a relay race, a revitalising reassurance through a panoramic view of the past – lent by flavours and facts that are local and trustworthy.

A Desolation called Peace: Voices from Kashmir

Edited by Ather Zia and Javaid Iqbal Bhat

Published by Harper Collins

2019

Price Rs 499.

The writer is an alumna of the Department of English, University of Delhi. She hails from Downtown Srinagar and has worked closely with Human Rights organizations like Amnesty India.

Like this story? Producing quality journalism costs. Make a Donation & help keep our work going.