China’s remarks hinting that it could send its army into Kashmir, after India sent forces into Bhutan’s Dhoklam plateau, could mean many things for Kashmir. With China Paskistan Economic Corridor that passes through the disputed territory is China’s interest in Kashmir unique?

A fable attributed to Aesop is about a monkey appointed as judge by two cats to settle a dispute over how to divide a piece of cheese they had stolen.

The simian judge, on the pretext of ensuring that the cats got exactly equal halves, kept taking bites out of the two pieces. When only two small bits of cheese were left the judge gobbled them up on the claim that this was due to him in legal fees.

The story of the Himalayan territories would be similar to that fable, if China is seen as the monkey judge eating away the cheese of many cats, on one pretext or the other.

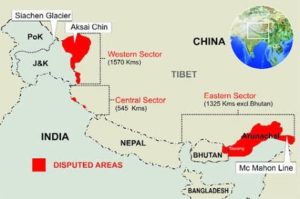

The first bite, of course, was Tibet in 1950. Large bites were then taken out of the composite territory of Jammu and Kashmir. Aksai Chin, an area of about 37,244 square kilometres, was seized during the 1962 Indo-China war.

The Chinese have since offered to exchange Aksai Chin for another piece of cheese – the Tawang region of Arunachal Pradesh.

“The disputed territory in the eastern sector of the China-India boundary, including Tawang, is inalienable from China’s Tibet in terms of cultural background and administrative jurisdiction,” Dai Bingguo, China’s former top border negotiator told the Chinese media in January this year.

Curiously, China is ready to accept the McMahon line on Tawang but refuses to recognise it elsewhere – insisting that it is an illegal demarcation drawn up the colonial British. But then the hallmark of Chinese border negotiations has been citing the British Raj documents when convenient and rejecting them at other times.

In 1963, J&K lost the Trans-Karakoram tract, under the Sino-Pakistan agreement. India has never recognised that agreement which gave China control over a 5,180 square kilometres swathe of northern Kashmir. And now with the proposed China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) set to pass through Pakistan-administered Kashmir, questions of sovereignty are bound to come up. No way India could have joined the ‘One Belt One Road’ initiative.

More opportunities for slicing up Himalayan territory looming ahead.

Chinese media has hinted at the possibility of the PLA entering the Srinagar valley, if invited by Pakistan. The rationale? The Indian army’s presence in the Dhoklam plateau of Bhutan that China disputes.

Writes Long Xingchun, Director of the Centre for Indian Studies at China West Normal University, in a recent article in the Global Times: “Even if India were requested to defend Bhutan’s territory, this could only be limited to its established territory, not the disputed area. Otherwise, under India’s logic, if the Pakistani government requests, a third country’s army can enter the area disputed by India and Pakistan, including India-controlled Kashmir.”

Xingchun has theories on how Sikkim, a state which has settled borders with China, became a part of the Indian union in 1975. “Through mass immigration to Sikkim, ultimately leading to control of the Sikkim parliament, India annexed Sikkim as one of its states,” it alleged. Here he forgets or ignores that the mass immigration into Sikkim was from Nepal and not India. Also, much of it happened more than a century ago under British rule.

An earlier Global Times editorial on July 5, 2017 had warned that the Sikkim question could be reviewed. “Although China recognized India’s annexation of Sikkim in 2003, it can readjust its stance on the matter.”

Xingchun dwells on how ‘India fears that China can quickly separate mainland India from northeast India through military means, dividing India into two pieces’. India, he says, has ‘interpreted China’s infrastructure construction in Tibet (Doklam plateau) as having a geopolitical intention against India’.

The problem for Bhutan is that it is not just the Doklam plateau that China is claiming. According to new maps released by China, Bhutan is required to cede a whole slice of territory stretching southwards from the Doklam plateau and beyond the present Bhutan-China-India tri-junction.

Being a flat pasture, the Doklam plateau has strategic value for China in the rugged, high-altitude region dominating territory in Bhutan, Bangladesh and Nepal, as also India’s Sikkim and Darjeeling territories. It cannot have escaped China that the Kalimpong division of Darjeeling district was originally leased from Bhutan and is readily accessible from the Chumbi valley.

China wants Doklam, a 269 sq km property on the eastern side of its Chumbi valley, so badly that it has offered to forego its claims in northern Bhutan at Jakarlung and Pasamlung, totaling 500 sq km, in exchange.

On the Indian side, Prakash Katoch, a retired general attached to the Centre for Land Warfare Studies in New Delhi, even wrote an article in 2013 suggesting that the King of Bhutan consider selling the Doklam plateau, since it is private property of the Royal family.

While Bhutan is treaty-bound to consult India on defence and external affairs, the Chinese insist on dealing directly with Bhutan.

The result has been a drastic reduction in Bhutan’s territorial dimensions from 46,500 sq km in 2010 to 38,390 sq km, according to news reports. On 28 June 2013, the Bhutan News Service cited Govinda Rizal, an expert on Bhutan based in Japan, to say that the country could ‘lose another 4,500 sq km or up to 10 percent of the country’s area, if Bhutan fails to scientifically resolve the longstanding boundary disputes with its northern giant’.

There are signs on social media that sections within Bhutan are now anxious for a quick border settlement with China even if it means losing the Doklam plateau – a piece of territory to which it does not attach the same value as China and India do.

On July 7, 2017 the Global Times published a piece by Wancha Sangey, a Bhutanese legal consultant titled ‘India uses Bhutan to secure New Delhi’s interest’ that is reflective of the new Bhutanese mood.

Reflecting Bhutan’s frustrations and fears over the Doklam dispute Sangey writes: ‘Bhutan has to be fully aware of the limitations of demands we can make upon China. And at the same time Bhutan is in no position to ignore the strategic interests of India. There is too much pressure. That is why Doklam the tri-junction Plateau is drawing multi-attentions.

It will be a blessing in disguise if China or India forcefully just takeover Doklam Plateau. The so-called status quo is endangering the status of whole of Bhutan’.

Sangey argues that a Sino-Bhutan border agreement, at whatever territorial cost, would help resolve the dispute between India and China over Arunachal Pradesh to the east of Bhutan. ‘So later, like Doklam, there is bound to be similar tri-junction situation. And there, too, China would not be compromising her national security for friendship with Bhutan.’

In a separate note to this writer Sangey said: “I hope both Indian leaders and our own Bhutanese leaders understand why I call for a Sino-Bhutan Border Treaty at the earliest. It (Bhutan) is not choosing China (over India) now. It is ensuring that at the least Bhutan remains as one entity not two separate parts – this tug of war between China and India pulls Bhutan into the whirlpool.”

Sangay’s fears of Bhutan being divided by India and China into two halves may not be unfounded. Chinese maps of Arunachal Pradesh (referred to by Beijing as Southern Tibet) are indeed alarming as they claim a large area reaching right up to Kanglung in east Bhutan. This means that Bhutan could lose territory in the districts of Kanglungon the east and SamdrupJongkhar to the south as well.

As a larger and more resourceful country India has options, including maritime ones. It certainly can control the choke point of the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago.

Already, Japan is building a 15 megawatt power plant on the islands. This week, the navies of Japan and the United States will join that of India for the latest of the Malabar naval war games series in the Indian Ocean — that can have only one adversary.

Whether these countries hold together in a crunch is untested. And India would be well advised to heed the dire statements issued by China’s foreign office, and avoid further escalation of the Doklam standoff, by all accounts an extraordinarily difficult situation.

The takeaway then is that the sooner the border is settled with China, that monkey judge sitting above South Asia, the better.

Ranjit Devraj was the regional editor of Inter Press Service. In the past he has been a special correspondent with the United News of India news agency. Devraj counts two years in the trenches (1989-1990) covering the violent Gorkha autonomy movement in the Darjeeling Hills as most valuable in a career of varied journalistic experience.

Disclaimer: Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position and policy of Free Press Kashmir.