Even after massacring 2.3 lakh Muslims in Jammu in Nov 1947, the marauders were still in possession of thousands of abducted Muslim women when the European hotelier Michael Harry Nedou and his Kashmiri wife Mirjan’s daughter Akbar Jehan walked in to avert the post-massacre crisis.

Barely eight months after she launched a mass campaign by distributing subsidised food to people against the rising cost of living, under the sun-setting Dogra regime in February 1947, the lady—whose mythical ties with Lawrence of Arabia hogged much headlines—had, perhaps, no idea that she would be in the carnage city by November 1947 to ‘bring them home’.

The 1907-born Akbar Jehan Abdullah was on the front-line in the region, drenched in the blood of 2.3 lakh butchered Muslims. Even after the Muslim neighbourhoods had turned into ghost towns overnight, the larger impending crisis was the uncertain fate of the abducted women, torn asunder by that crimson autumn.

When some of the abducted women began coming home, they were turned back.

Not many families could reconcile with the fact that their abducted women—daughters, sisters, wives, and even mothers—had returned home with bulged bellies.

“It was in such a disturbing scenario,” says Mohammad Yousuf Taing, Sheikh Abdullah’s auto-biographer, “that Begum Abdullah went to Jammu.” Taing recalls the heightened ‘communal’ tensions at Jammu, where even the daughter of Chaudhry Ghulam Abbas was abducted.

“If such a leader’s daughter could be kidnapped,” the octogenarian author—being celebrated in NC circles for his penmanship—curls his hands and face to say, “then imagine the plight of the commoners! When Abbas’ daughter was picked up, he was in jail — like most of the Muslim leaders of Jammu.”

Mohammad Yousuf Taing

But soon after the carnage orchestrated by Sangh goons, in connivance with the fallen Dogra regime, the emergency ruler’s wife known as Begum Jehan in NC circles visited Jammu, with Delhi’s support.

“When she reached Jammu,” recalls Taing, now spending his post-retirement life at his Rawalpora residence, “the echoes of the tragedy were even resonating in New Delhi, governed by Lord Mountbatten. His wife Lady Mountbatten also came to Jammu and joined hands with Begum, who played a humanitarian.”

At that historic junction when the partition-fueled tensions were still afresh, the partners of two powerful leaders tried to avert the post-tragedy crisis at Jammu.

Then, Lady Mountbatten was the chief of the Indian Red Cross and Begum Akbar was its JK head.

In Jammu, the nerve-jangling stories of abduction, rape and killing of Muslim women awaited Akbar Jehan. Among the pack of accounts were the spine-chilling stories about the countless women—who jumped into the Chenab and Tawi to save their ‘honour’.

Shortly, she established camps for the abandoned and abducted women in Jammu.

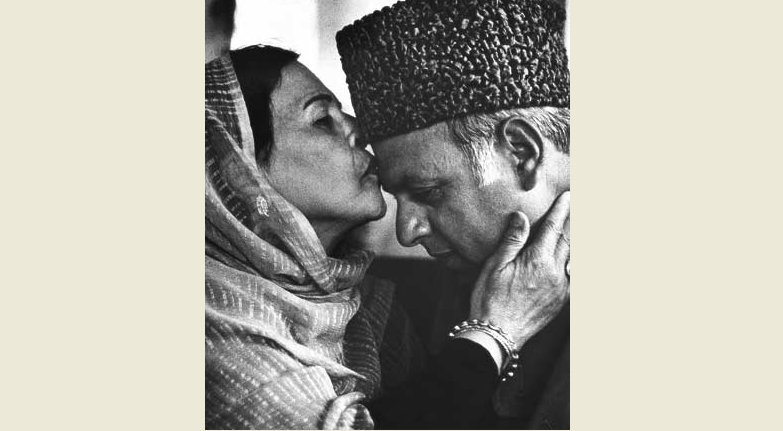

Akbar Jehan (right) with Lady Mountbatten (centre).

“Begum with the help of her team recovered thousands of abducted women,” Taing recalls. “She kept them at a house built near the TV Station in Jammu.” But it wasn’t just recovery. Rehabilitation was equally a difficult task ahead of her which had to be taken at war-footing.

But such was the crisis heaped by the no-holds-barred carnage that even after hordes were sent to the other side, over a 1000 women abducted by marauders could never be traced.

In many cases, however, whereabouts of the family members of the abandoned women could not be established, writes Zafar Choudhary, a Jammu-based journalist in his book Kashmir Conflict and Muslims of Jammu.

“In many such cases,” he writes, “Begum Akbar Jahan organized mass marriages with voluntary Muslim men in Jammu.”

Taing explains the marriage method, thus: If any woman had relatives left, Begum would make it sure to hand her over to them.

“If not,” he says, “then as per her wish, she would be either sent to Pakistan or married to a Muslim volunteer.”

At least, Taing says, 2500 carnage-freaked Muslim women were either married or remarried with the help of Akbar Jehan.

“Imagine,” Taing says, “what would have happened to all these women if Begum hadn’t rehabilitated them? What would have happened to Jammu Muslims? Perhaps, not many would have been there today.”

Sheikh Abdullah (left), Akbar Jehan (centre) and Mohammad Yousuf Taing (right).

But despite being the Prime Minister’s wife, it wasn’t a walk in the park for her in Jammu. The communal mindset would ensure shielding her rehabilitation works at a time when Muslim addresses were being changed with Hindu nameplates. The pervading murderous mood wanted to shunt her humanitarian work out.

“Apparently,” Taing says, “the Lady Mountbatten’s presence in the town discouraged those marauders to derail Begum’s work. After all, Edwina Mountbatten was the Governor General’s wife. And Begum was smart enough to use Edwina’s influence to help trace the abducted women.”

But the larger question remains, how did Akbar Jehan recover the abducted girls?

Taing says, as the word spread that they were in the town, many survivors approached Akbar Jehan and alerted her about the abducted girls.

“Among those who approached her were Hindus, too,” he says. “They had hid Muslim girls in their homes. They came and asked for her help.” In that way, many women were recovered.

In her endeavour, says Akbar Jehan’s son Mustafa Kamal, she was ably supported by Mirdula Sarabhai and one Om Mehta of Baderwah.

“My mother and her team members had learned how several Muslim women were lured by their abductors on the pretext of an illusory Pakistan trip and instead kept them in captivity in Jammu, and adjoining areas,” says NC additional General Secretary. “Ironically, those were the locals who had acted both abductors as well as rescuers of those Muslim daughters in Jammu then.”

For Kamal, his mother’s role, unlike Karan Singh’s mother, was significant.

“Unlike Hari Singh’s wife, Tara Devi’s rabid communal role in instigating the carnage,” Kamal says, “Begum used her authority to placate the larger crisis. She played a stellar role. It was not easy to do what she did in that vicious environment. Anything could have happened.”

Later when Sheikh Abdullah went to Jammu flanked by his deputy Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, Taing says, Akbar Jehan used Bakshi’s contacts in Jammu for recovering more women.

Some 40 years later, her Jammu gesture rescued her son’s life.

It was 1989 and before Farooq Abdullah would publicly say that he wanted to leave Kashmir “to play golf in England”, one Captain Rasheed—the militant guide—from Muzaffarabad was sent to assassinate him on a Tangmarg road.

Akbar Jehan with son Farooq Abdullah

As he laid an ambush, one of his comrades alerted him, “Oye Gujra…”.

“When I arrested Rasheed,” says AM Watali, the former DIG Kashmir, “he told me: ‘How could I kill my own Gujjar brother?’ He had changed his mind after learning that Farooq’s mother was Akbar Jehan of Gujjar descent, who had helped in averting the post-1947 Jammu crisis, mainly involving Gujjar Muslims.”