In the fast shifting sands of Kashmir militancy, a professor-turned-rebel’s massive funeral unwittingly reminded many of the longest surviving militant from Ganderbal whose fall had almost waned militancy from Kashmir’s erstwhile kingmaker constituency.

As guns rattled one fall day in 2011 from Ganderbal’s fading green woods, the villagers dismissed it as the usual wild confrontation. But the impression lasted till a battery of army men came downhill, minutes later, with the biggest hunt of the decade — Hizb’s top commander Mushtaq Khan, alias Janghi. In police records, he was Mushtaq Killer.

Mushtaq’s death instantly evoked the Qazi Nisar memories. The cleric’s killing by Hizb gunmen had erupted parts of Islamabad with “Hizb Murdabad” (Down with Hizb) chants. Unlike the seething southerners of 1994, Ganderbal men quietly witnessed an old mother’s street jubilation — cheering, laughing and distributing sweets.

In her euphoria, she would tell the mourners how the fallen had once trained gun at her son. Possibly a rare aberration from Mushtaq, many said, and curtly dismissed the mother’s mad moment.

The mixed mood erupted after army and police finally got the longest surviving militant commander in Kashmir. The moment Major Gen Gurdeep Singh, GOC Victor Force called a media conference at 5-Rashtriya Rifles Battalion headquarters in Ganderbal, he aired the victor’s vibes.

“Mushtaq Khan alias Mushtaq Janghi, commander of the Hizbul Mujahideen, who was involved in 30 odd civilian killings and active for more than a decade in Ganderbal district was killed in a brief encounter in the forest area of Gutli Bagh in Ganderbal with police and 5-RR,” he said.

Controlling the militancy in Ganderbal as A+ category militant, Mushtaq was the host and the guide of militants in the region. After his passage, only eight militants—both foreigners and locals—were left in the district. Months later as forces gunned down his lieutenant Ghulam Nabi War alias Haq Nawaz, Ganderbal became “militancy-free”, barring occasional skirmishes and strikes.

A decade before his demise, in the erstwhile home-turf of Abdullahs, “the most dangerous” militant commander, Hamid Gadda alias Bambar Khan was giving a tough time to the armed forces.

Before his death in March 2000, Bambar had bumped off many cops, army men, Ikhwanis and informers in a series of attacks across central and northern Kashmir. Besides managing a number of IED attacks on the armed forces in Kashmir, he had blown several Army vehicles on the Kangan-Sonamarg highway and Wangat-Kangan road during the Kargil war.

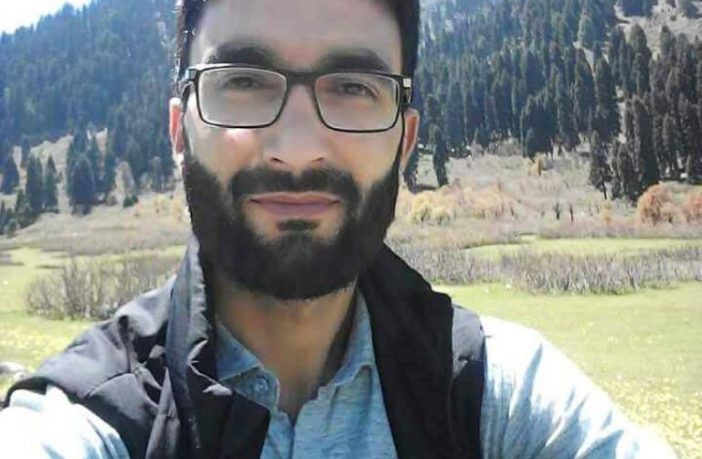

Mushtaq Khan during his youth.

Bambar Khan’s exit became Mushtaq’s entry.

Coming from Ganderbal’s Gutli Bagh area, housing the Pashtun community of Afghan descent, Mushtaq was only 18 when he left home to become a militant. For the next 18 years, he had a unique distinction of surviving amid vast human intelligence and spy networks, that have now reduced the lifespan of a militant to months only.

“From the very beginning,” says Manzoor Khan, Mushtaq’s younger brother, “my shaheed sibling was a mischievous child, who would choose jungle over school.”

Gutli Bagh’s dense woods were then known for housing foreign militants, forcing villagers to declare it a prohibitory zone for their children. But Mushtaq would often slip away, apparently to avoid regular frisking and crackdowns downhill.

Then one day, he sent a word to his home: “I can no longer withstand their atrocities.” He had joined the armed struggle at a time when the Afghan militants were making rounds of the valley. In Ganderbal, Mushtaq was their “eyes and ears”.

With time, he found a sizeable support around him. In the long run, this support determined his longevity as an insurgent.

Legend is, when two Ganderbal teenagers joined him, they soon developed ideological friction. Much of that came from Mushtaq’s stern and stubborn nature.

“You wouldn’t blame the man for his ‘final word’ command because he was enjoying a lion’s sway over the masses in Ganderbal,” one of the boys, now trader in town, says. “However, failing to handle power properly also earned him his share of woes.”

Within a month, as the boys decided to desert the commander, one of them wasn’t lucky. Apparently the “lion” felt betrayed, and was seen standing near the boy’s bleeding body, with his smoking gun.

“His power-frenzy behavior and increased meddling with the villagers’ personal matters cut a self-styled don’s image of him,” says Mushtaq’s former militant apprentice. “This is where he lost his fans and earned foes.” Even as he faced an open opposition, he says, the hardened insurgent hardly bothered to mend his militant methods.

At home, his family kept facing regular army raids and summons to force him to surrender. At times, in rage, the army would even beat their dog — before shooting him dead, one day. “They thought he [dog] was a trained informer, helping Mushtaq to break cordons,” the sibling smiles.

But whenever he would visit home, Manzoor says, “Mushtaq would turn down the surrender offer, saying: ‘I’ve left for a cause and will die for it’.”

When he finally fell in a brief gunfight, his family turned down the official death version. “He was the master in his job and could’ve easily escaped,” Manzoor says. “He was poisoned and then killed. They gave us his body at 11 in the night, directing us to bury him before 11 in the morning.” In case of delay, army had warned to take back the body.

Today seven years after his death, Mushtaq is a part of folklore and conspiracy theories. One conspiracy theory surrounds his death.

Twenty days before his killing, a tall Pashto man sporting kitten-whisker had filed a missing report of his son with the Ganderbal police. A few days later, cops informed him that his son had joined Mushtaq.

Intriguingly, when Mushtaq’s and his associate’s fate was sealed in the October 2011 gunfight, the missing boy would be captured alive. Months later, as he walked a free man, Mushtaq’s family and locals cried foul.

“That boy is rarely seen in the area now,” Manzoor says. “We believe he was planted as a mole by the army. He had all the reasons to be one. With Rs 12 lakh on his head, Mushtaq was a prized scalp for anyone.”

But as the insurgency waned in Ganderbal after Mushtaq’s passage, not many had anticipated that, years later, the district would host a massive militant funeral of its professor-turned-militant.

In a brief stint of militancy that lasted only for a day, 32-year-old professor Mohammad Rafi Bhat, was killed in Shopian’s Badigam village. Bhat was a professor in the Kashmir University, and had given a lecture on Friday, May 4.

Two days later, he was among the five militants killed in Shopian’s Badigam village. The gunfight ended before Bhat’s family could reach the gunfight site, to convince their son for surrender, after receiving a call from the armed forces. The family learned about his abrupt death on their way to Shopian.

The fresh demise may not mean much for Ganderbal, but it did reinvigorate the memories of its militant past at a time when the military smokescreen is indeed thickening across Kashmir.

Afshan Rashid contributed to this story.

Like this story? Producing quality journalism costs. Make a Donation & help keep our work going.