Be it Sangh Parivar’s anti-special status crusade or the dusted autonomy war-cry, a shy-soft-spoken professor of the Kashmir University captures the unreported tensions in the state governance structure right from 1947 to ’89 in his maiden book. Among other things, the professor’s treatise maps New Delhi ‘balancing act’ of equating cries for self-determination with development schemes.

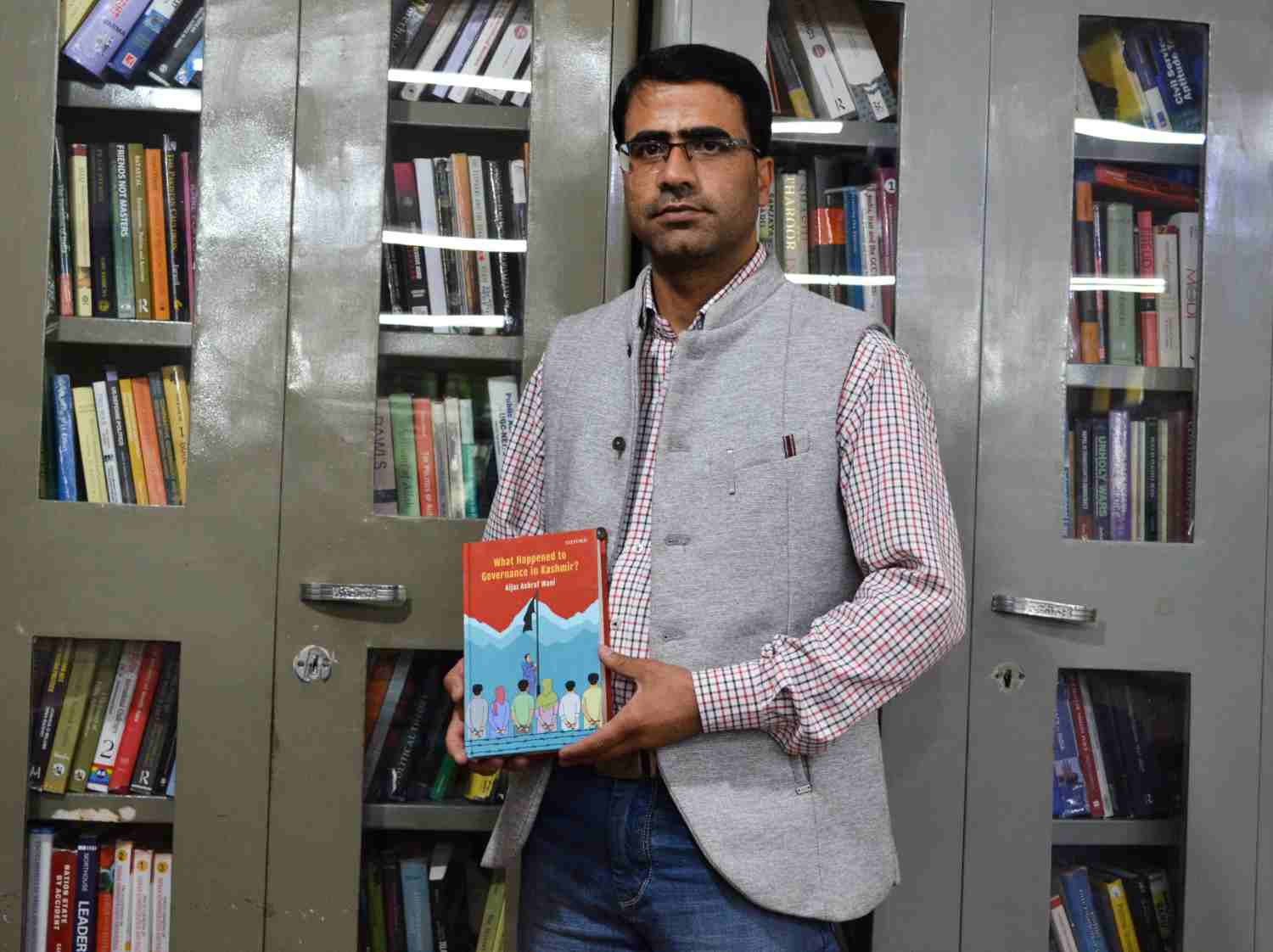

In a shower-soaked spring day in the postcard campus of Kashmir University, an average-built professor quietly retires to his office room, tucked on the first floor of a building. Outside, in the corridor, his chirpy students, carrying bounded assignments in their hands, await his nod. The single-floored department is the address of the oldest Political Science Department of the region, where politics is an all-encompassing fact of life.

The bespectacled young professor takes a careful glance at his newly released book—promising fresh insights about the governance structure in Kashmir—resting on his table, before giving it another fleeting reading.

The 400-pager—What Happened to Governance in Kashmir?—authored by professor Aijaz Ashraf Wani and published by Oxford University Press India, methodically maps the second-coming, on a meek power term, of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah in Kashmir, among other things.

The author makes no bones about the manufacturing consent, the traded loyalties and shrinking space for non-violent dissent in Kashmir. Terming it as New Delhi’s default K-management, the professor says, such response was never a ‘mistake’.

“Being a conflict state, J&K is a ‘state of exception’,” Prof. Aijaz begins, airing the typical lecturer’s mannerisms. “As Giorgio Agamben argues, ‘Within the state of exception, the sovereign becomes absolute and unreferenced, requiring neither legitimacy nor legality for eternal justification.’ ”

It labours no argument, he continues, that conflict is the overarching factor of Kashmir’s polity, economy, society, culture, human rights—infact every minute sphere of its life. “Though the main stakeholders of the problem—both in terms of rights and costs—are Kashmiri people, the problem can be resolved if the two claimant countries—India and Pakistan—realize that this issue is not only a human issue of the people of the state, but it has been costing heavily on the people of the two countries as well besides acting as a great stumbling block in the process of their development.”

Unfortunately, he rues, both the countries have made it a grist to the mill of nation-making. “Perhaps we’ve to wait for unforeseen developments within and without the subcontinent to pave way for resolution of this long standing issue or may be a people’s movement across the sub-continent to push governments to end this long standing hostility and make sincere efforts for the resolution of all issues including Kashmir.”

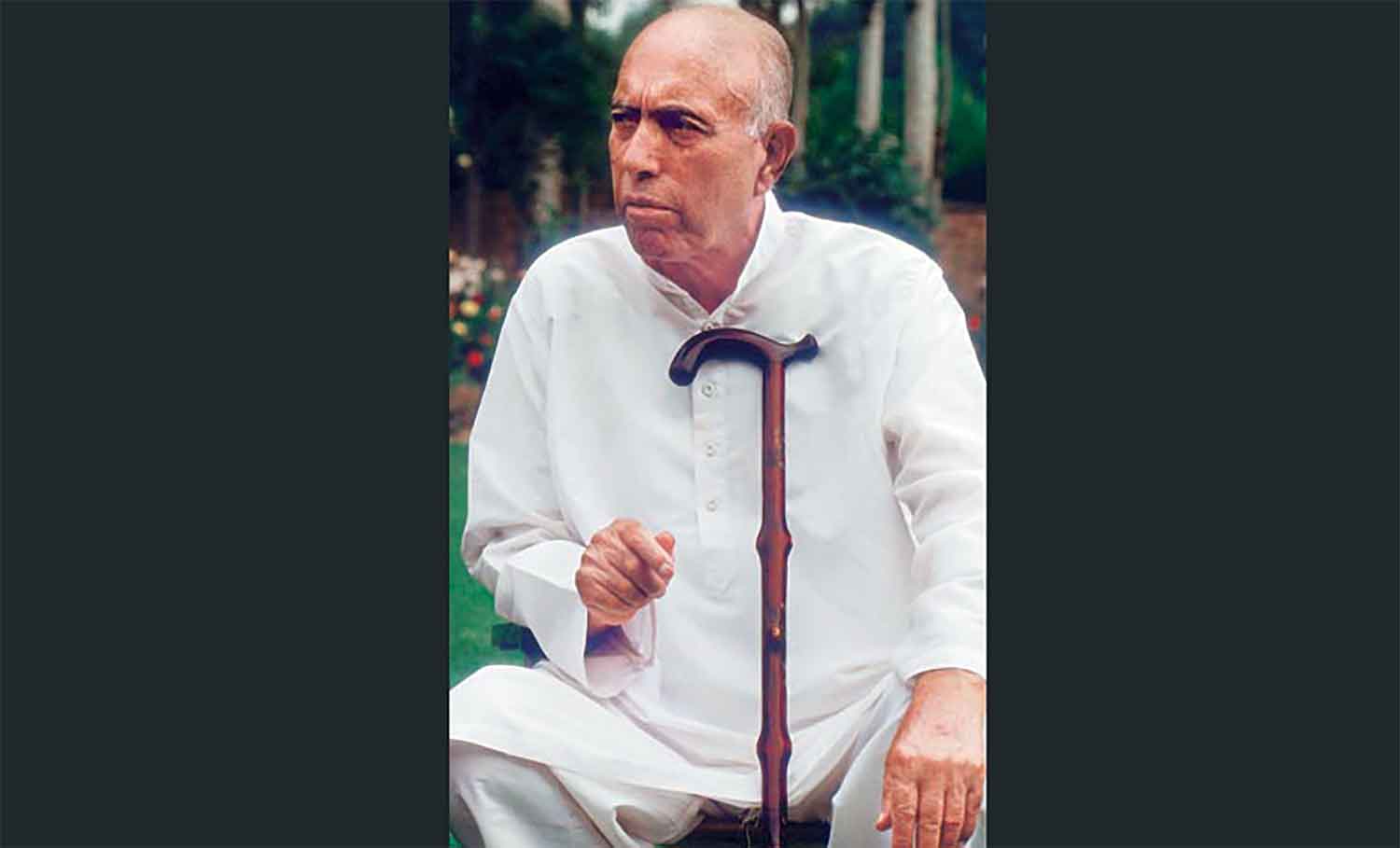

Professor Aijaz Ashraf Wani. (FPK Photo/Wasim Nabi)

Coming back to his book’s subject, the young professor says, Governance in Kashmir is largely scripted around ‘state-centric relational approach’ where state has tried to control and dominate the society and even when it has interacted with other actors or opened up for some accommodation, it has been with a view to expand/implement its discourse.

One of the main highlights of the book, however, is its extensive Sheikh-era mapping.

After winning a landslide victory in the 1977 assembly elections, the book says, the grand Abdullah continued to play the politics of manipulating popular political sentiment.

“[But] To be fair to Abdullah, he never ceased to nurse the dream of an “independent” Kashmir, but he was caught between his two mutually opposing ambitions — the yearning for independence, and the quest for power which destroyed him as well as Kashmir,” the book says.

While detailing Abdullah’s second governance stint, the author quotes Josef Korbel’s objective—yet legendary—assessment of Abdullah: “The story of Sheikh Abdullah is a sad and sorry one. It is a story of a patriot, once passionately devoted to his people’s welfare, but one whose patriotism was too shallow to reject the temptations of power.”

Born in 1982, in southern Kashmir’s Nowdal Tral countryside area, Aijaz Ashraf Wani mainly grew up on the campus of Kashmir University. His father retired as Professor of History at University of Kashmir, while his mother is a housewife.

A meritorious student throughout, his decision to opt for Social Science stream immediately after his 10th class had raised eyebrows. “It was quite unusual during those times when everyone was crazy about medical and non-medical and wanted to be only a doctor or an engineer,” he says, smiling, as his students continue to wait and talk in the corridor outside. “Social Sciences were sort of looked down upon.”

He eventually graduated from Amar Singh College and joined Department of Political Science, University of Kashmir for his Masters, in 2003. Three years later, he got registered for M.Phil programme and in November 2007, got appointed as Assistant Professor at KU’s Department of Political Science. It was a couple of years after his appointment that he started his Ph.D programme and got awarded in April 2014.

“Like other Kashmiris of my age I grew up in a deeply conflicted environment,” the young professor continues, as another spell of spring shower starts drenching the campus outside. “When armed rebellion broke out in Kashmir I was around 7 years old, thus am a participant observer of the death and destruction which the state, especially the Kashmir Valley, has been reeling under for nearly three decades now. My bitter experience is that Kashmiris have become used to the loss of men and material because they have they suffered so much on daily basis during the past three decades. Therefore the efficacy of silencing dissent through repression seems of doubtful consequence.”

Prof. Aijaz’s research mostly focuses on Kashmir—governance, conflict, identity politics, electoral politics etc. His Ph.D research topic was “Governance in Kashmir Since 1947”.

His book studies the state of Jammu and Kashmir from the perspective of an ‘exceptional state’ rather than a ‘normal state’, a periphery on the margins of the centre, and thus shifts the focus from the central grid to the local arena. It’s a telling tale on the state of governance in Kashmir; the policies and strategies adopted by Indian state and the successive patronage governments to manage the conflicted region. In the process the book unfolds the nature and functioning of the state, politics and governance in Kashmir from 1947 to 1989.

Governance in Kashmir, he says, has always been subordinate to the immediate needs of restoring ‘peace’ even though the strategies proved self-defeating in the long run.

“All the tactics tested so far can be categorized as conflict management instruments rather than conflict resolution policies, that actually should be the aim of good governance,” the professor continues. “Since the conflict has been managed mainly through coercion, corruption and denial of democracy rather than addressing the root of the crisis, the problem has become graver with the changing times underlined by growth in education, exposure and information networking.”

The interference of Hindu rightwingers in the affairs of Kashmir and the meek submission of the central governments to the pressure added fuel to the fire besides negating the ideological justification of Kashmir’s accession to India, the author says.

Immediately after assuming power in 1975, the book notes, Sheikh Abdullah constituted a four-member committee headed by Mirza Afzal Beg to draft a proposal for the restoration of autonomy to Kashmir.

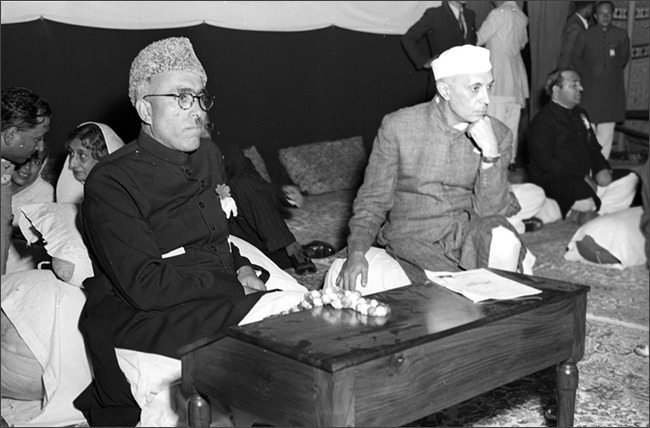

Sheikh Abdullah as Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir.

“As Beg knew that there was no scope for restoring the autonomous position of Kashmir, he avoided working on the proposal,” the book notes. “After his dismissal from the cabinet, Sheikh Abdullah appointed two committees to submit separate reports on the issue. One was headed by D.D. Thakur and the other by G.M. Shah. Thakur in his report opined that this demand would only impair relations with the centre. The Sheikh observed silence thereafter.”

It’s also important to mention that in 1975-76, the author says, the National Conference published a pamphlet, Why Autonomy to J&K State?

“A delegation of the National Conference, which was invited to attend the All India Congress Committee meeting at Chandigarh, attempted to distribute the pamphlet among the members,” the book maps the Sheikh era. “Indira Gandhi took serious note of this and had the move stopped, and did not provide Sheikh Abdullah the opportunity to address the meeting. Sheikh felt so humiliated that he emotionally asked his cabinet members to be ready to resign.”

Inside his office, the professor carefully veers the conversation towards what he calls the “futile pursuit” for NC’s biblical belief—Autonomy.

“The ‘autonomy’ experience in Kashmir during 1947-1953 failed in practice,” Prof. Aijaz explains. “With no power to raise funds (especially attract international funding) and to lift the geographical siege, Kashmir was thrown from a frying pan into the fire unfolding in serious financial crisis and shortage of basic necessities sullying the position of the otherwise the then undisputed leader of Kashmir. Therefore, the demand for autonomy without the authority to raise international finances and restoring the geographical centrality of Kashmiris is certainly misplaced; more disastrous that it proved during 1948-1953 when in comparison to the present, the societal demands from the state were utterly minimal.”

But while working on the subject—Governance in Kashmir—the professor found himself face to face with many issues. Besides the vastness of the subject matter, Governance covers every conceivable thing on this planet. “Therefore,” he continues, “I had to be selective.”

At the same time being a student of Political Science, he had to justify the place of governance in the subject of his discipline. “And while marrying governance with politics I had to satisfy simultaneously both the political scientists as well as the scholars of governance, which was a challenging task,” he says.

Even though the subject of his study was of recent past, he says, the archival sources were extremely scanty which speaks dismally about documentation in Kashmir. “So I would go again and again to the archives and other places hoping against hope that I may get my hands on something meaningful. And many times the people who were there at the archives, who were generally good, would say kuch din pehlahi to aaya the aap, yahan kay hai (only few day back you had visited, there is hardly anything here).”

Also, the oral sources have also become extinct for the want of tapping them at the appropriate time, he says. “Interestingly, those interviewees who had ideological leaning towards one or the other government, were reticent in being balanced in their account of the times.”

Indeed, he states, scholars at places like Kashmir, have to strike a balance between many extremes. “Some interviewees completely refused to be forthcoming for fear of reprisal as they suspect our credentials.”

But terming Governance as an unploughed field, the author says there’s an urgent need to make Governance an independent area of research. “So far, we still lack in informed research,” he says. “However, for doing quality research it is no less important to provide requisite support and facilities to the scholars and ensure security of their livelihood as is the policy in the developed countries.”

Meanwhile, Sheikh Abdullah continued speaking from his heart, but could do nothing practically, the book notes.

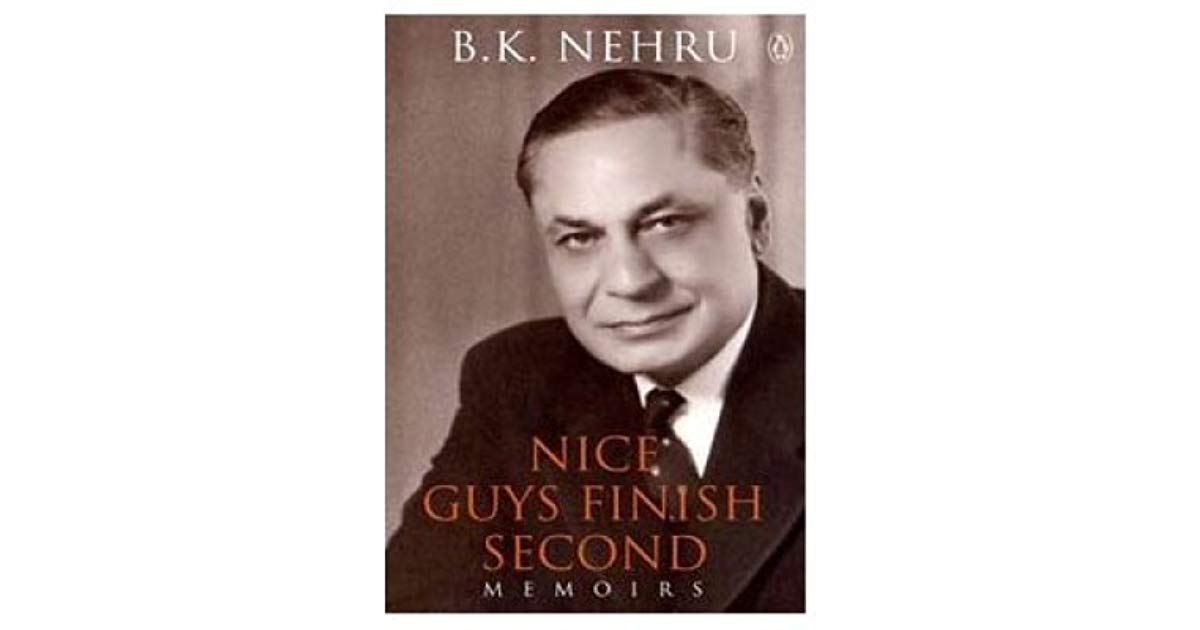

“On the day of the National Conference’s victory in the 1977 elections, he gave a statement to Voice of America pledging to work for the restoration of autonomy,” the book reveals. “Governor B.K. Nehru, with whom Sheikh frequently used to spend his leisure time discussing freely and frankly the affairs of J&K, besides “the whole universe”, writes: ‘…it became clear from our conversations from time to time as well as from the difficulties he was creating in accepting wholly the Constitutional demands of the Centre that his objective was… the eventual creation of a separate independent state consisting of at least the Valley together with such Muslim areas of Jammu division as could be tagged on to it.’

Ahmad, principal secretary to Abdullah, corroborates Nehru’s account with thick detail. He observes that the ambition to carve an independent position for Kashmir stayed with the Sheikh permanently, till his last breath: ‘He was till his end toying with and working for the idea of a Greater Kashmir comprising the valley including Kargil District, Muslim majority areas of Doda, Bhaderwah and Kishtwar and parts of Udhampur District namely Ramban, Batote, Gool Gulab Barh, Banihal, and Poonch and Rajouri Districts of Jammu province with minor adjustments for reasons of topography. It was with this objective in view that a special Division of R&B Department was created reviving and converting the old Mughal Road linking Rajouri District with Shopian of Pulwama District in the Valley into a permanent and all weather road. Similarly, work on construction of Daksum (in district Anantnag) Kishtwar road was started in right earnest. This road was to provide a link with Kishtwar, Doda and Bhaderwah. The Central Government was also asked to upgrade, improve, and realign the Batote-Doda road, which was subject to frequent landslides and resultant closure of the road for days on end.’ ”

As he continues talking about his book—especially the Sheikh era, one can’t help asking the suave professor: Since you happen to detail some unknown facts and facets of Sheikh M. Abdullah’s life and politics—especially towards the fag-end of his career, what’s your reading on the ‘tallest leader’ of Kashmir?

“Though my book is not only about Sheikh Abdullah and his government as it deals with whole period and all the governments from 1947 to 1989, however, obviously given the overarching influence of Abdullah on politics and governance of J&K, he becomes a sort of central figure. I have revisited Sheikh Abdullah as a politician and administrator after 1947. Sheikh Abdullah (and consequently Kashmir) became a victim of his illusion that after acceding to India, Kashmir would be as ‘autonomous’ as was it during its Princely period (1846-1947). He did not compromise with this ideal till his death, though practically he could do nothing about it.

Sheikh Abdullah sincerely believed in Nehru’s friendship. In his simplicity he was innocent enough to understand that he was dealing with a statesman taught in the art of setting the trap.

Sheikh Abdullah was not a great man. He proved to be a common leader especially after 1947. Unlike a great man he played tricks with the collective will of the people to swing the deal in his favour, and that too a humiliating deal which ultimately led to the crisis Kashmir has been reeling under since 1989.

Sheikh Abdullah died a dejected person. He repented over his own chosen role as a ‘sole spokesperson’ at crucial junctures. He was even repentant and remorseful about the nomination of his successor.”

Sheikh with Nehru.

But as a chief minister, the professor’s book notes, Abdullah, at least, demonstrated a difference.

“He was reticent in accepting Indian Administrative Service officers from the centre to form a part of the state cadre; nor did he permit the chief justice of the high court who was a Kashmiri to be transferred. Abdullah also resurrected the Resettlement Bill. Besides other things, the bill signalled to the people a move towards the reunification of people divided by the Line of Control — and the possibility of returning to the time when the state was undivided,” the book notes.

Writing about the challenges which the authority of the centre faced on Kashmir when he took over as governor, B.K. Nehru says: ‘The challenge to the authority of the Centre which the Sheikh was making when I took over charge were three.

The first was his refusal to permit the Centre to send IAS officers to form part of the state cadre as was custom in every other state of the Union.

The second challenge consisted in the refusal of the Sheikh to permit the transfer of the acting Chief Justice of the state and his replacement by a nominee of the centre from outside the state as was, and is, the practice in all the other states of the Union.

The third problem was much more serious. Some considerable time earlier a bill had been introduced in the Assembly by a private member, entitled the Resettlement Bill. It provided that residents of the state who has left it between 1947 and 1954 to go to Pakistan could be allowed to come back and resume all their rights as Indian citizens.’

Indeed, the author says, in the contemporary political history of Kashmir, Abdullah is the last example of the head of government trying to assert his authority. “He differed, though politely, with the governor who refused to sign the Resettlement Bill.”

And what transpired between Abdullah and the governor is interesting to hear from the then governor himself, as it alludes to an assertive role of the chief minister as the representative of the people vis-à-vis the head of the state as representative of the central government: ‘I warned Sheikh that I would not sign the bill as it was so clearly unconstitutional. His argument was that it was none of my business whether the bill was constitutional or not; that was the business of the Supreme Court. I should sign the bill when it was passed, if anybody had any objection to its constitutionality they could go to court.’

The book also talks about Congress-National Conference Confrontation.

FPK Photo/Wasim Nabi

No sooner did the Sheikh take up the reigns of government than the Accord was converted into discord, following the confrontation between Sheikh and the Congress party over the politics of hegemony, which continued throughout the Congress-backed rule of Abdullah and after, Prof. Aijaz writes.

“…people construed this embittered relation between Congress and the National Conference as a fight between New Delhi and Srinagar to dominate Kashmir in a struggle among unequals,” the book reveals. “Abdullah issued a press statement saying, ‘since the Congress had withdrawn its support to me, therefore, the Accord between me and Mrs Gandhi should be treated as cancelled.’

“All factors mentioned in the preceding discussion help us fathom the sustained popularity of the Sheikh till his death. Soon after his demise, the “rebels” who had “withdrawn” during the hustle and bustle of the Abdullah government, to conceive a new strategy to actualise the will of the people left half-done by the mass leader, returned to revive the suspended course of history, which found considerable favour with the young generation, more than ever, in the changed circumstances.”

Like this story? Producing quality journalism costs. Make a Donation & help keep our work going.