When the office of Kashmir University Student Union (KUSU) was razed to the ground in May 2010, the message was loud and clear: No more student politics! Amidst such a dictatorial stance, a 23-year-old student activist emerged, who has adopted a fighting approach to put the authority down on its knees – several times, already!

This is 2010 – their office, which once used to be their home, has been demolished. Under the eyes of heavily armed policemen inside the wide 263 acres Kashmir University campus, they, in dozens, staged a three-hour sit-in raising anti-authority slogans, only to fall on deaf ears.

The demolition carried in the name of “campus development”, made the authority’s intentions crystal clear: No more student activism in Kashmir’s highest seat of learning.

Nine years have passed by, KUSU still remains displaced. Although post-demolition, the union has only politically evolved more and more; adopting the larger Kashmir narrative, with its members regularly targeting the “state atrocities” in the form of press releases.

However, it wouldn’t be wrong to say that the university, through the act of demolition, was successful in silencing a huge sect of student activists from across the valley. They say, at Kashmir University, students don’t have a voice. The authorities take the decisions and there are no two opinions about it.

Amidst such an autocratic stance from the side of the administration, has risen a student activist who has adopted a “legal” approach to break the campus stereotype – Naveed Bukhtiyar, a law student himself and the founder of J&K Students Movement (JKSM).

Comprising of about 15-20 members, Bukhtiyar’s JKSM is roughly about a year old. Whether it is protesting the university’s “baseless” bans, or fighting to free the detained students, JKSM has been slowly evolving as a “guardian angel to thousands of voiceless students” in the valley.

But the ultimate aim of 23-year-old Bukhtiyar is to reignite the student activism in Kashmir, and he is slowly and steadily moving towards his goal.

“I have learned the art of questioning,” he says, with a smirk. “And I do have the right to information, don’t I?”

Right to Information or RTI has been Bukhtiyar’s go-to tool. He has a clear roadmap: “Question, take the matter to the court, and fight till victory.”

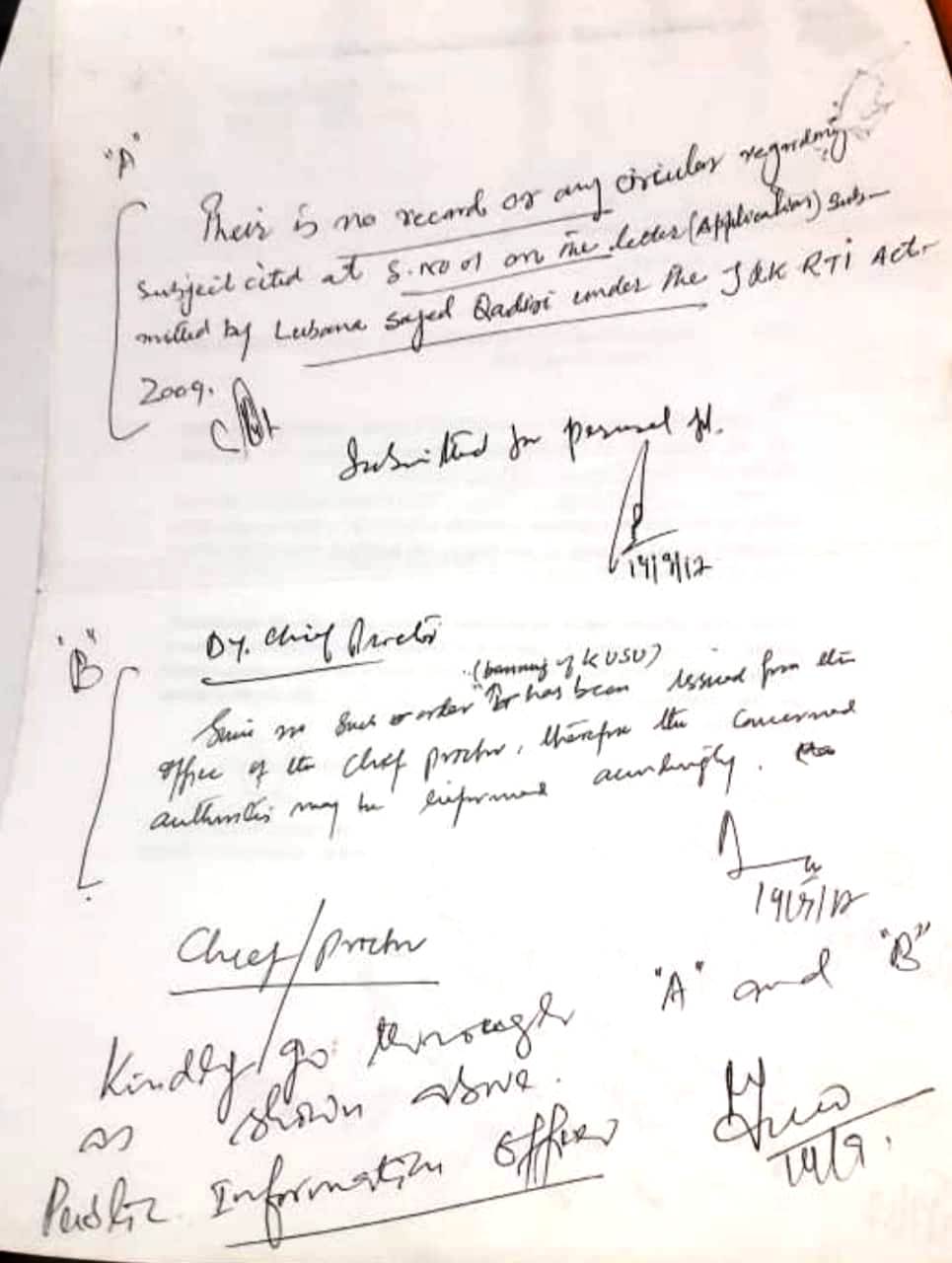

In June 2017, he filed an RTI to KU’s Public Information Officer (PIO) seeking the copy of the ‘government order’ that directed the university to demolish the KUSU office.

And, to Bukhtiyar’s surprise, the reply from the PIO broke the nine-year-long myth.

“There is no record or government circular regarding the (query cited by the applicant),” the reply read.

Thus, the ban on student activism in the valley, Bukhtiyar says, is “illegal and forceful”.

“For almost a decade, the students were kept in a notion that student activism in banned in Kashmir. Why? Does the authority fear to share their power?” he asks.

Student politics is very much active in campuses like JNU, DU, and several other prime colleges, but it is banned in Kashmir’s most recognised university; the reasons, remain unknown.

When these universities can have student unions, why not KU?

“I would humbly tell you that these universities are far ahead of us in academics while we are lagging behind,” is how the Chief Proctor, Dr Naseer Iqbal justified the ban in an argument published by the Kashmir Narrator titled ‘Should on-campus student politics be allowed?’

He further added, “We have to wait till we are at par with such institutions academically then only we can afford a students’ union here.”

In the counter-reply, a former student leader Peer Mohsin Shafi, wrote: “NAAC has awarded Grade A to KU and still the authorities say they are not at par with JNU, which is also Grade A. The argument not to allow students to form a union, therefore, sounds hollow.”

ALSO READ: The shadows behind the student outrage in Kashmir

From hostel facilities to the menu of the canteen, it’s the University that takes all the calls, Bukhtiyar continues. “If there was no government order to demolish the KUSU office, why did they do so? Isn’t student politics our democratic and constitutional right?”

Bukhtiyar, with an RTI copy in his hand, has taken “uncountable” rounds of the vice-chancellor Talat Ahmad’s office, but not once has the “busy man welcomed” him.

“His (Ahmad) personal assistant says there is a procedure to get an appointment. Why so? Fine, the VC must a busy man, but can he not take out a few minutes to give ears to his students?” Bukhtiyar asks.

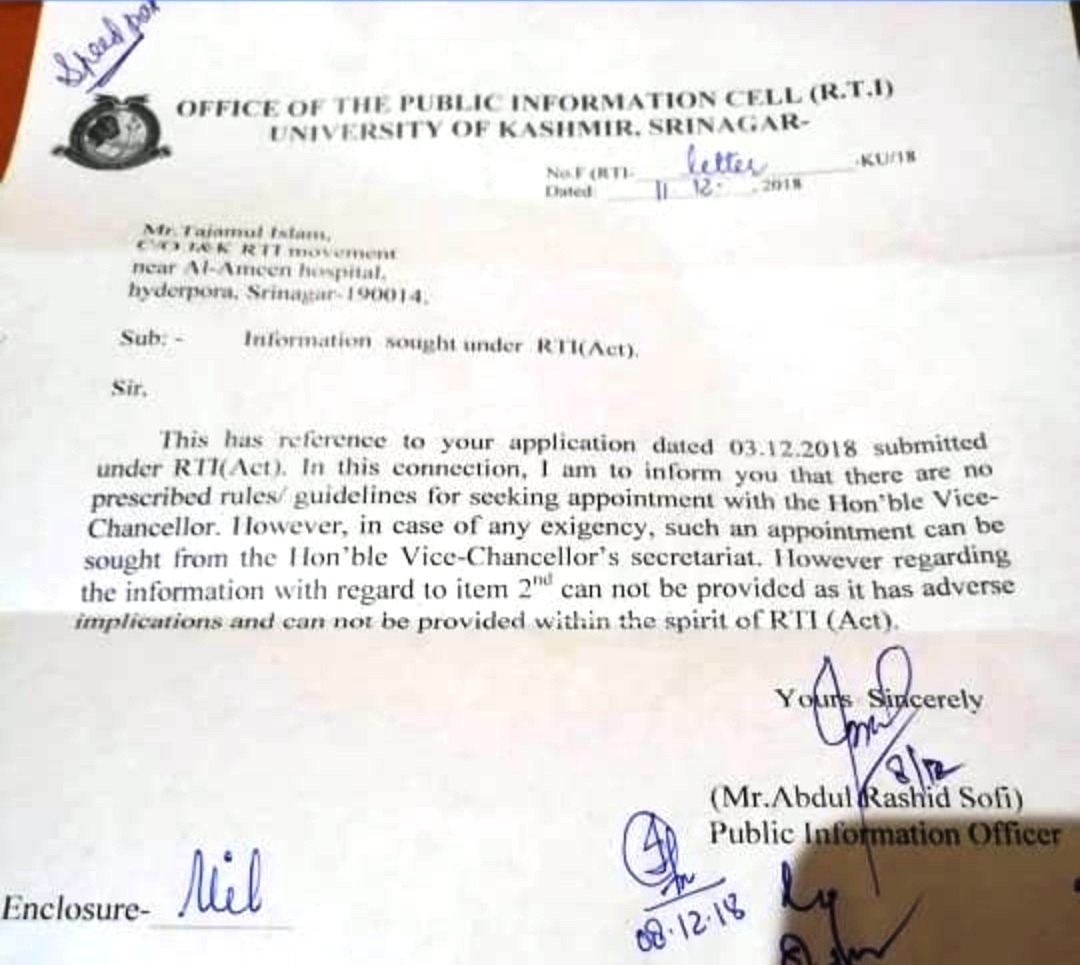

He did not give up. He filed yet another RTI asking the procedure to get the VC’s appointment, and this time, the reply wasn’t any surprising for Bukhtiyar.

The PIO said: “I am to inform you that there are no prescribed rules/ guidelines seeking appointment…However, in case of any emergency, such an appointment can be sought from the (VC) secretariat.”

The RTI replies thus show that the authority doesn’t want to bring back the student politics back to the campus, and the reasons for it, remain unknown.

Even when this reporter tried contacting the VC on phone, he ducked the question and sighted himself “busy” for any comment.

But Bukhtiyar is determined: “I am waiting for the exams to get over. For one last time, I am going to submit a written application to the VC and the Dean Students Welfare Association. If they reply, good for them, or else I am going to directly approach the High Court.”

And with a tongue-in-cheek comment, he concludes: “I am sure at least then the VC won’t be busy.”

Like this story? Producing quality journalism costs. Make a Donation & help keep our work going.