It was on this day, 24 years ago, when Charar-i-Sharief went up in raging flames, to chagrin and heartbreak of Kashmiris. In a fierce militant-military clash on May 11, 1995, many natives lost their homes and were subsequently displaced from Nund Reshi’s town. Today, many of them still find it hard to make peace with the gutted shift.

For over two decades now, Haleema has been troubling her routine with her sudden thoughtful appearances. In that lost state, she revisits her old home, which she sees rising up in flames amid deafening gun rattle and screams in Nund Reshi’s totem town.

The dateline concretized in her mind is May 11, 1995, when Indian army finally advanced to hunt Pashtun militant commander, Mast Gul and his guerrillas. Even as Gul vanished from the burning town like a phantom, Haleema continues to stay put, thinking about her lost home.

In that smouldering town, rented with cries and wails, she still sees curls of smoke emanating from her home. What remains in her sight are the black-burnt mud walls of her neighbourhood, in the backdrop of a pervasive sight of wreckage.

A burnt Charar township. (Picture courtesy: Meraj-ud-din)

These imageries have stayed with her like a lingering nightmare. And whenever she thinks of her lost neighbourhood known to house revered Babas, fairy-tale Kangri-makers and potters in its Algerian stairway-like houses, a dreadful feeling grips and unsettles her.

That Charar might be gone, but Haleema’s restless mind still savours it, as a stark memory.

And that’s how some of the displaced natives recount their association with Nund Reshi’s refurbished town.

As a routine now, displaced Haleema, who’s in her late 50s, often visits her saint, especially when the lifeless world she has come to dwell wears her down.

After prayers, she spends some time with her old neighbours, before taking a ride to her new home, nestled 4 kilometres away from the shrine, in Satellite township aka Alamdar colony. Even as she walks back home, Haleema still longs for her lost streets and old address.

Haleema while offering Zuhr Nimaz inside the shrine of Nund Reshi. (FPK Photo/Malik Shaib)

Much of this daily struggle of the displaced Charar-i-Sharief natives might be unnoticeable, but the internal displacement has created its own issues for the closely-knit community.

Before Gul arrived on the scene, in that wintery day during mid-nineties, the township was known for its own distinct features and routines. It was driven by the sense of oneness, as Hilal Anjum, a 35-year-old tutor in Alamdar colony, recalls it.

“After the fire, that oneness waned,” he laments. “We used to share every moment of life there, even food with each other, as the atmosphere was so conducive and cordial to us.”

The majority in the old town were economically sound, Hilal continues.

“We would cater to visitors coming to pay obeisance at the shrine. We used to serve them and in return, they would spend in the town. It would boost local trade,” he says.

Inside her new home, Haleema regretfully talks about her emotional and spiritual attachment with her burnt birthplace. In a newly designed satellite town, she says, she’s surviving than living.

“In my eyes, Charar was a big house with uncountable siblings living under the same roof,” she recalls, with a glint in her eyes. “There was no restriction on anyone to roam around and every other person seemed like a family to us.”

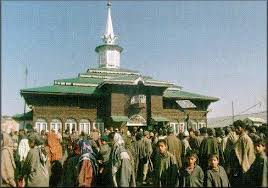

Old Charar Shrine.

But shortly after the inferno created displacements, the life for the fire victimized families in Alamdar Colony became miserable. They couldn’t immediately make sense of the sudden shift in their lives. Many of them are still living a traumatic, nostalgic life with emotional attachment with their blissful birth burg.

Alamdar colony, their new address, came up 28 kilometres away from Srinagar. Most of the fire victims were compensated and about 150 households were allotted plots in the satellite town.

Today, the new domicile of the displaced Charar natives houses more than 8000 households—150 among them include the influential Baba families of old town.

Holding religious sway over the town, Babas were Charar’s home-grown shrine custodians. Reverence and respect for them stemmed from their authority on mystic Sheikh Ul Alam—Nund Reshi’s life and his farsighted writings.

“It’s different here,” says Javid Baba, a local shopkeeper of the satellite town. “I don’t know who lives next to my house. But in our old home, we would freely enter in our next-door neighbour’s home. It was a big family.”

Especially, the town’s senior citizenry still carries strong traditional feelings with them.

“Our town was the hub of religious festivity,” says Zooni, 70, another displaced native living in the Satellite colony. “We would share meals and moments. Anyone could come and stay with us. But those horrific flames changed the whole scenario forever.”

Even as the Satellite town has become an “economic hub” over the years, with sound administrative setups and urban lifestyle, the feeling of loss and letdown runs deep.

A view of Alamdar Colony. (FPK Photo/Malik Shaib)

“After that unfortunate incident, many of us were dumped here and left to fend for ourselves,” says Tariq Ahmed, 35, a grocer of the satellite town. “That fire didn’t only render us homeless, but also forced us to switch to different lines of work. It was a different place for us, bereft of the old town’s bustle and clientèle. We never made peace with the place.”

But some of their cousins and family members—nearly 20000 households—still live around the shrine. Their houses were mainly spared by the big blaze. Unlike new towners, the old towners “feel lucky”, for their proximity with the shrine.

Meanwhile, inside Haleema’s home, the good old days still dominate the discourse.

She makes mention of Ramzan and recalls how a bunch of girls from old town would welcome the holy month with Islamic songs and ‘Roff’.

“Today, our girls can’t even think about it,” she rues. “That fire indeed changed Charar forever.”

Like this story? Producing quality journalism costs. Make a Donation & help keep our work going.