Last week’s fierce street protests in parts of downtown Srinagar appeared redux of its defiant past. But beyond its moniker image, lies the cultural cradle reputation of the place, which is now struggling to keep pace with time.

Walking about Srinagar can get daunting. Firstly, because of the harmless jitters of being new to the city and its landscape. Secondly, owing to the prejudice you bring along. No matter how hard you try to shake off baggage from the latter, it plays on your subconscious.

But what’s damaging as a consequence is that you begin to view everything around you strictly from two extreme perspectives. You either over-romantacise the place and its people, or you over-demonize it – every random stare or an unwelcome smile on the streets is an omen.

Either way, one cannot help but force meanings and symbolism out of the milieu and its every filament. Against such a backdrop, seeing graffiti sprayed across shop shutters and walls, sending out messages across the socio-political spectrum of Kashmiri thought can get unnerving.

For the uninitiated, like me, Downtown Srinagar finds mention in contemporary memory amongst news reports and editorials. It’s a place, I’ve been told, that has long witnessed strife at its rawest and a long-drawn decay of human life, as I know it otherwise, at its worse.

For an outsider though, who hasn’t seen the metamorphosis for himself, today’s state of affairs is normal (as per my definition, that is).

I hop on to one of Srinagar’s minibuses at Maisuma Chowk. The place again becomes unique after I’m told of the significance of one of its residents. Passing through Red Cross Road, sitting through another 15 minutes of the bus ride, I reach the red coloured arches marking our entry into Downtown Srinagar.

Gateway of the Downtown, Srinagar.

The surroundings aren’t vastly different from what I’ve witnessed elsewhere in the city, the flowing Jhelum for company, similar structures, the weather. Except that it’s a lot more calm and silent – comparatively, that is.

It’s past noon by the time I reach there, and people retreating for their afternoon prayers could be the reason. The roads do have your template vehicular passing and pedestrian traffic, but not as overwhelming. And the fact that inspite of all the perceptions of ‘strife-ridden’ Downtown Srinagar that you brought with yourself, you hardly spot armed personnel or even the occasional patrolling jeeps, is intriguing.

I later realised that it’s the tenser development in localities of Kashmir’s southern districts that warranted a majority of the attention and presence of the forces.

I head down to another well-spaced stretch, flanked by timber shops on either side, when the reading on the shutters became obvious. The immediate shutter I find myself outside of, bears marks of a graffiti and that appears to be white washed.

A few closed stores down the road, the need to whitewash these messages, for those who did, becomes all the more apparent. The haphazardly sprayed texts range from, “We want Freedom” to clarion calls asking people to boycott the elections. Sometimes, these graffiti aren’t even self-explanatory. Perhaps, their metaphoric meaning best lies deciphered by their intended audience.

FPK Photo/Lesley Amol Simeon

Either way, I am told, the civil authorities in the region loose not much time before white-spraying all over these messages. But quite evidently, they’ve been outrun.

Passing one stray canine after another, I finally enter Khawaja Bazaar. The marketplace also houses the Ziyarat Naqshband Sahab shrine – which is named after the renowned mystic from Bukhara (in present day Uzbekistan), Khawaja Syed Bha-u-Deen Naqshband. The locality thus borrows its name part from the mystic – who is credited to being the founder of the Naqshbandi order – and part from Khawja Khawand Mahmood – another Sufi saint from Bukhara, who constructed the present day Naqahband Sahab shrine.

Adjacent to the Martyr’s Graveyard is where the final remains of his son Khawaja Moin-Ud-Din Naqashbandi, rest. Since the gravestones are inscribed in Urdu, there’s not much I can uncover here – except for an article I had read online earlier which talks about the blurry meaning ‘Martyr’ can have in this context, given the legacies of the men, buried in the graveyard.

A man praying at Khanqah-e-Moula shrine. (FPK Photo/Lesley Amol Simeon)

Of the handful of narratives surrounding the arts and crafts, Kashmir has become synonymous with today, is one that places the descendants of the Sufis, at the starting point. Along with other influences to the region’s cultural fabric, they are also credited by some to have introduced the people here to traditional crafts and skills.

Standing proof are the scattered neighbourhood stores of copperware and embroidered dresses, among others. But standing in a counter of sorts simultaneously, are stores selling a variety of contemporary, mass-churned products – such as western wear stalls, general stores and mobile boutiques.

Having said that, the tense undercurrents Nowhatta and Downtown Srinagar command is lost on me nonetheless. Mostly because its a relatively peaceful day out and there is no extraordinarily streetside confrontation playing out or simply because at just two days in the city, you’re still the third party, per say.

The grimness to the region’s recent past is made evident only by the reoccuring graffiti and the somewhat underplayed social life. The clatter at the shops and the hop in the pavement strolling of the localities is as understated as it can be – especially in the shops circling Jamia Masjid.

The mosque, the oldest in Srinagar, offers unparalleled peace. The road lining the entrance to the mosque doubles up as the protestor’s battlefield, I’m told, complete with tear gases running rampant even within the mosque’s premises – reiterated by the graffiti on its compound wall.

Jamia Masjid, Srinagar. (FPK Photo/Lesley Amol Simeon)

Though the faith of it’s devotees isn’t lost on the visitors – the folded hands at the central fountain or resting knees in front of the sanctum – one can also spot youth sitting on the trimmed lawns or parked at different quarters of the premises, some in conversation, some on their phones.

This is just one of the many motifs that seem to suggest a transition of sorts – from the old to the new, from what has been to what should or will be, from probably hanging on to relics to adopting newer means of escape. Transition, metamorphosis, struggle or compromise – you be the judge.

Of course, mere spotting of youth on their cellphones isn’t the sole mark of a transitioning period, if at all there is one set in motion at the moment.

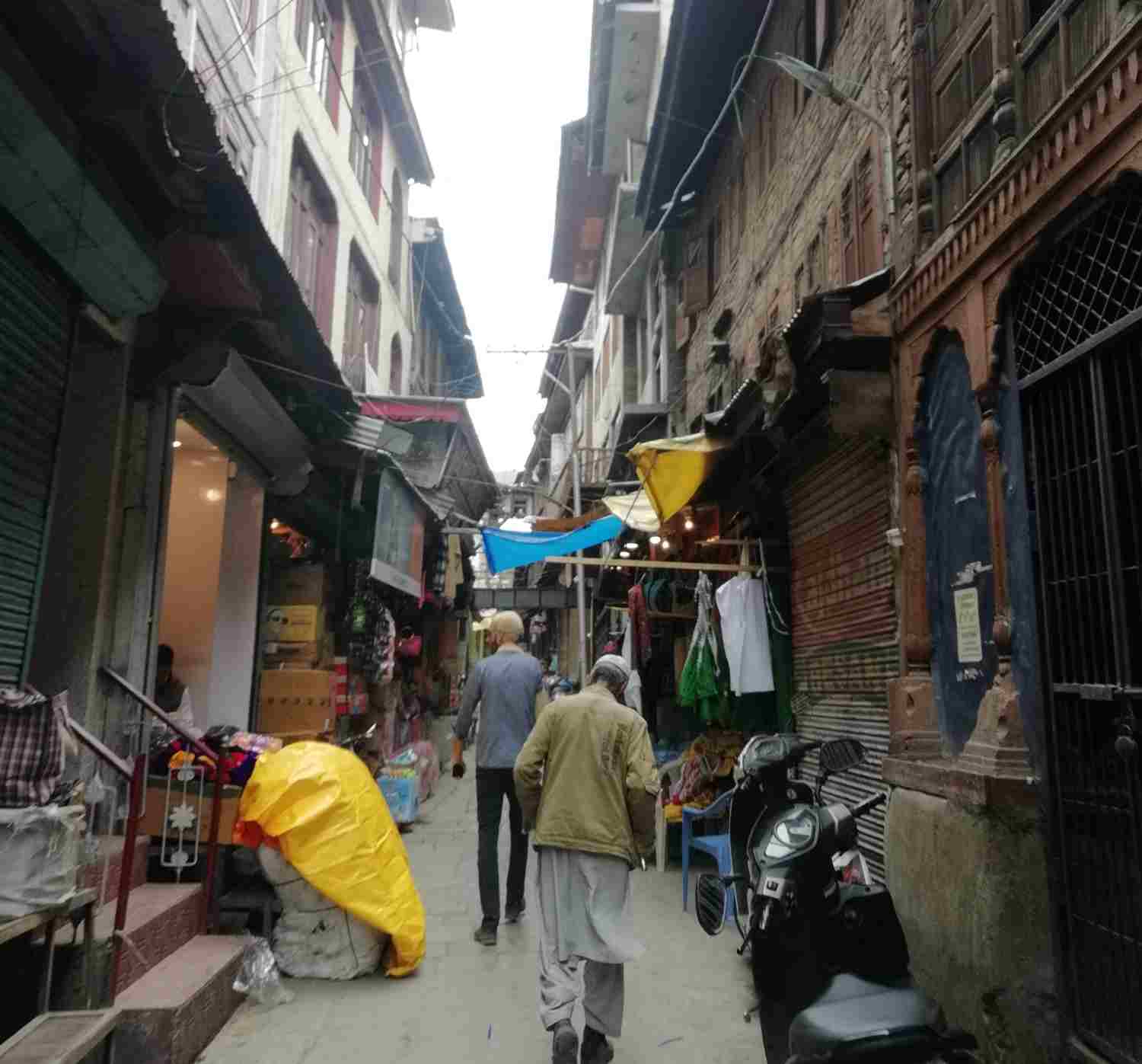

After strolling about on the main roads, venturing into bylanes ironically offer you the more elaborate of pictures. Busier than the main streets, in these bylanes are bustling workshops and stores. These include stores selling tobacco, packing small parcels from the modest heaps of the powdered leaves, stores selling spices and copperware workshops, where the artisans are busy with what seems like everyday tasks of drilling, soldering and flattening the metal among others.

What these places, whether in the bylanes or on the main roads, have in common – along with stores selling typical carpets and embroidered apparel – is that not many are manned by people my age or older. At these stores you’re mostly welcomed by men, white haired and long bearded – possibly from the generations that either live in denial of contemporary times and cling on to the days gone by. That, or they show the grit and passion to do what they’ve always known to do best.

A bylane of Downtown, Srinagar. (FPK Photo/Lesley Amol Simeon)

The river banks of the Jhelum paint a similar picture – albeit a lot more telling.

The houses, resting on the banks are the ones newspaper articles and travelogues highlight about Downtown Srinagar – visibly dated wooden and brick structures. One look and you can tell they’ve stood witness to everything the Jhelum has flown through, flown over and survived. But that’s for the poetic.

For the amateur, the overbearing element here is the facade of these houses – tattered, windows barely in place, wooden bars sticking out, holes on their tiled roofs. These were all residential, I’m told. But people barely live here anymore. By the nights, even the functional structures in the bylanes on the banks are stores which are shut down, it’s owners returning to their homes. Life on the banks more or less, is a matter of survival, pushing oneself by the day.

Again none of this is visible to the naked eye, more so for the tourist. What is though, are remnants of the used-to-be life by the banks. For one, at a number of spots by the river, are squatted men, washing clothes.

On closer sight, these are Pashmina shawls. Washing them by the banks and drying them on the structures behind, is an art and an industry in itself. Justified, given the hype and patronage the craft demands elsewhere (read: metropolitan cities).

On the banks of River Jhelum. (FPK Photo/Lesley Amol Simeon)

But reality remains, that the said practice is on the downslide, next to extinction. One of the reasons one could speculate for this, could be how such skills find lesser takers to master, among members of the newer generation. This has probably led to the decline of such industries, which are fundamentally, a set of skills.

The irony here being, the picture of the tattered structure I stop to click by the banks, has a board hanging out that reads ‘Kashmir Pashmina Embroidery Textile Cooperative Ltd.’. And another reads, ‘Gani Textile Silk and Woolen Mills.’

While walking along the banks, one step to another, tracing the canals alongside, I spot to instances where temples stand right next to mosques. When asked if these temples are functional still, I’m told that some of them in fact are maintained by the members of the Muslim community.

Downtown Srinagar was far from what I had expected to be. More so, what unwelcome opinions, warnings and preconceptions had expected of the experience. True, the locality does have leftovers of recent protests and confrontations – in terms of weary structures and combustible graffiti. But lying alongside, appears to be a narrative of people holding on to ‘normalcy’ in spite of the turbulence.

This is again made evident by a number of physical leitmotifs – posters pasted across the face of the locality, announcing tuition classes, the cafe named “Downtown Cafe” among other eateries and designer boutiques and stores like that of Raymond. This alongside examples, where certain relatively newly built buildings with window designs and motifs painted on them, as opposed to the century old structures who have such designs carved into them.

The locality does have to its credit of being politically conscious and active even, but Downtown Srinagar spins realities that are running in parallel and under the saga made popular or major. And this isn’t difficult to spot. Even for a rookie reporter, on his maiden visit.

Like this story? Producing quality journalism costs. Make a Donation & help keep our work going.