A slew of summertime flood predictions cast a looming shadow on Srinagar where battle for spaces has long turned flood basins into housing colonies. Bemina being one such contentious residential address remains a telling comment on Srinagar’s ‘inorganic’ expansion and the perils it stores for its populace.

Whimsical weather forecasters apart, unfading murky skies did renew the flood threats in Kashmir this summer.

As a new normal now, any prolonged downpour unsettles the Valley. Many trace this disturbing weather trend from the devastating fall of 2014 — when Jhelum went berserk and made muck of South Asia’s second oldest city.

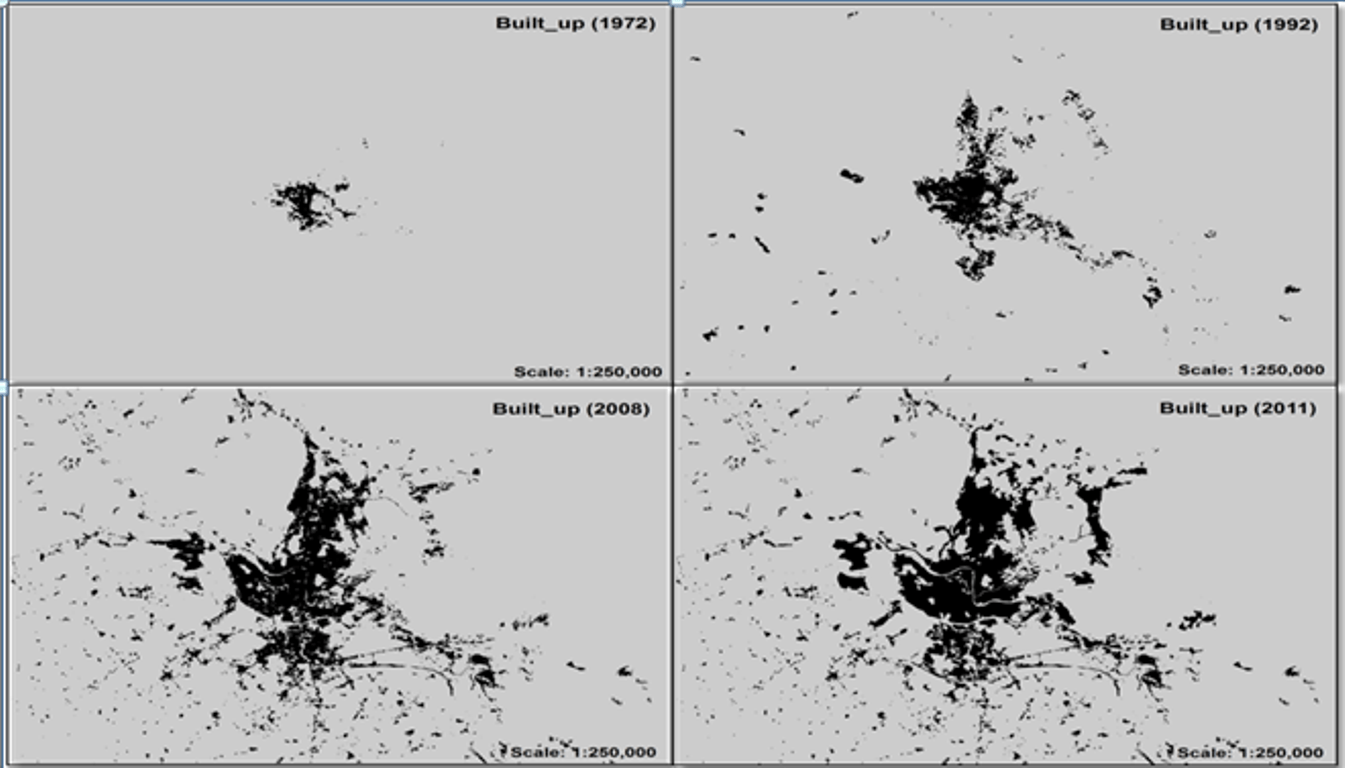

Part of the blame for the huge loss was put on the inorganic growth of the city. And Bemina being the mini-city emerging from the swamps is the sample of how Srinagar expanded and made a mockery of the urban planning.

Calling Bemina a huge disaster, Saleem Beg says the bigger problem with the area is that it blocked the natural drainage system of the city.

“The natural drainage of the city starts from Lal Chowk and goes down to Wular Lake,” Beg, INTACH chief, says, sitting in his office in yet another overcast day in Srinagar.

“With the emergence of Bemina, the natural drainage stopped. And the result is: With just three hours of rain, Sanat Nagar gets flooded; within 5 hours, Jehangir Chowk gets flooded and 10 hours of rain, everything gets flooded. So Bemina is not just a wetland but drainage, too.”

As a long-established flood sponge, Bemina’s left side—now shaping up into a new and unstable (flood-prone) Srinagar—witnessed unabated land filling over the period of last 30 years.

What used to be swamp was encroached to an extent that Bemina apparently lost its ‘notified flood zone’ status. It has been classified as vulnerable area, which can get submerged if large precipitation takes place in higher contours and a flood of high magnitude hits.

In his calm office, Beg terms this wetland mess and its menacing outcome as an upshot of the ‘institutional memory loss’.

Back in the day, Beg says, he tried to make sense of the emergence of Bemina by availing the copy of its plan. But like Nallamar land filing, he says, he couldn’t trace any document.

“I don’t know if Bemina was built by any design or on somebody’s wish, as our state doesn’t have institutional memories,” he says.

ALSO READ: Srinagar’s sordid saga: Dwelling in disaster-prone areas

“But something did go wrong there despite availability of good engineers. I tried very hard to get a copy of Bemina design, even when I was at a very senior position in the government, but I couldn’t get it.”

The problem is also on the planning side, he says.

“You build a road, a hospital and government offices in a marshy area and then expect that people won’t build houses there. That’s sheer idiocy,” he says. “I’ve visited the coastal areas of Orissa. They seemed to have learned lessons, as they’re building structures which can withstand hurricanes. But here, we just rely on God.”

It’s due to this belief system, Beg says, that nobody seemed to have learnt any lessons from 2014 floods.

“2014 shocker should’ve awakened us,” he says. “We should’ve learned how to drain out the flood waters without substantial damage, construct resistant buildings and improve our drainage system. But instead, we’ve only plagued the flood-basins with construction spree. That was our response to the natural calamity!”

And all this happened right under the nose of planners, enforcers and engineers.

“There’s no answer to it except that there’s total callousness in the system,” Beg rues.

In normal course, disasters like 2014 flood should’ve set the experts thinking. But as Srinagar watcher, Beg, sees no course-correction, the city seems to be under clear mismanagement. And the way, the system is allowing the housing clusters like Bemina to crop and mushroom further makes the whole urban planning a shoddy affair.

ALSO READ: How conversion of Bemina from flood basin to residential area endangered Srinagar

But before building Bemina, Beg says, planners should’ve thought that it would choke the whole city.

“Even if ours isn’t the first city to reclaim land in flood channel, but still there should’ve been a provision for an outflow,” Beg says. “And the irony is that whatever provision of drainage was left there was filled post 2014!”

Beg points out that outside the realm of journalists, no one made any noise on the issue. But why didn’t the state’s appraisal team ask the basic questions, remains a baffled query.

“While nobody is asking for punishment, the mistake should be identified and rectified,” he says. “But it’s not happening. And that’s why the remaining channels along the Bemina Bypass were filled and that too post-2014. That was not done by an encroacher, but the state government!”

The ‘construction-craving’ citizenry is equally responsible.

“We’ve this carefree attitude to say: ‘Allah sab theek karega’ (God will take care of everything). And then, we leave it to Him. And when God gives us a second chance after disaster like 2014 flood, we remain reluctant to learn our lessons. That’s precisely the tragedy with us,” Beg concludes.

To be continued…

Part III: The rot inside a wetland