When Kashmir’s celebrated English poet Agha Shahid Ali was ‘seeing Srinagar from New Delhi’ amid communication blockade in his homeland during nineties, a postman from Srinagar was braving curfews and clampdowns to deliver ‘crisis mails’ to people. What he witnessed during those trying times is a small window of Kashmir’s dreadful era.

One of the darkest hours had already dawned in Kashmir, when postman Mohammad Ibrahim stepped out on manned streets with a bagful of letters. It was another disquieting day in early 1990, and the watchful postman was walking through winding alleys towards Srinagar’s Karan Nagar.

Predominately populated by Kashmiri Pandits, the area wore a deserted look that day. Most of the houses were vacant with open doors.

At Srinagar’s TRC area, Ibrahim had earlier seen many of these Pandits stepping inside the SRTC buses. What appeared as a ‘fleeting journey’ to him has so far proved to be a ‘ride of no return’.

But that day, Ibrahim had arrived in Karan Nagar, with a letter addressed to one Sundar Lal.

Inside an unruffled lane, he cross-checked the name and House No 35, carved in black letters on white marble stone. It was the address he was looking for.

At Lal’s residence, the postman saw heavy baggage on the front porch. It made him speculate that the inmates were also mulling migration. He knocked the door — once, twice, thrice.

There was no response.

When he was about to turn back, someone called out from inside: “Who is this?”

“Postman,” Ibrahim swiftly replied, in his quivering voice.

Someone opened the main door for him and the postman stepped inside a pitch-dark corridor. Hardly anyone was visible inside the house filled with anxiety.

“Namaskar Mara,” he greeted the invisible inmates, in a typical Kashmiri Pandit style.

“Please come inside,” an anxious woman appeared before him.

“There’s a Selection Letter in the name of Miss Radika Pandita. It’s addressed to Sundar Lal, who is she?” Ibrahim asked the lady, who, by then, was joined by a thoughtful man.

“She is my daughter,” the man, introducing himself as Sundar Lal, replied.

“Where is she?”

“She left for Jammu last night with my brother…”

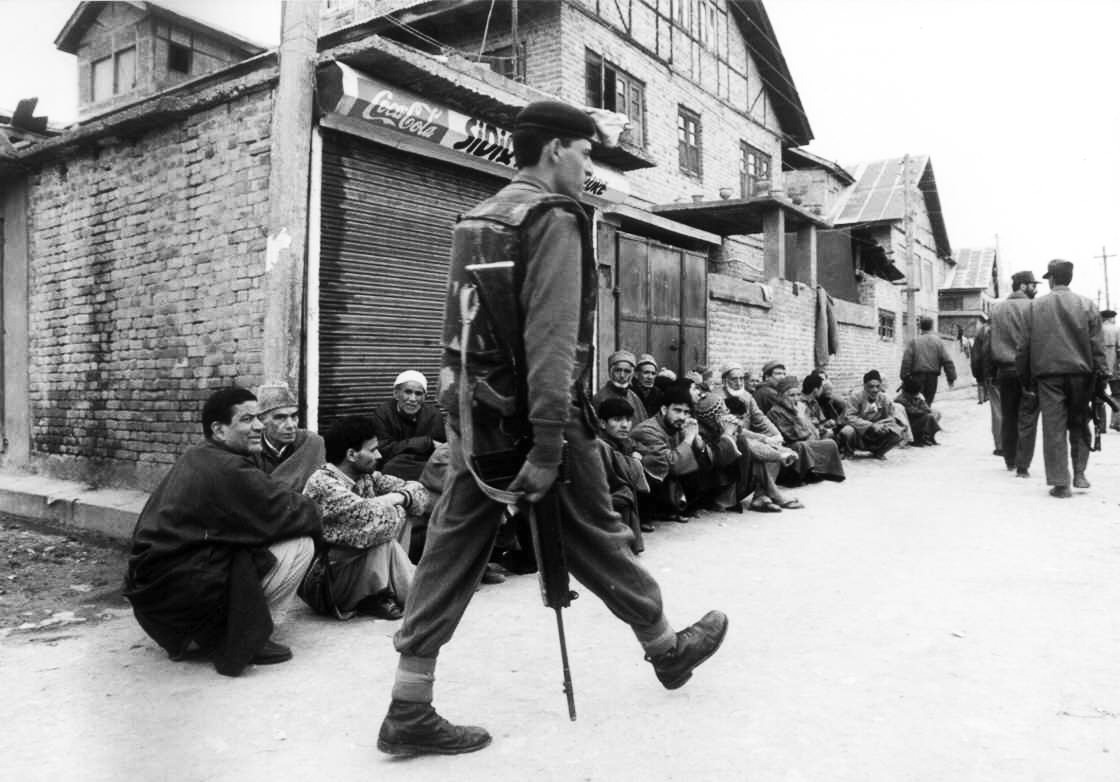

Representational Picture.

The couple opened the letter and abruptly exclaimed with joy. It announced that their daughter had cracked MBBS in Government Medical College, Srinagar.

They hugged, and cried in each others’ arms.

“I was waiting for this big day for long,” Lal, overwhelmed with joy, told Ibrahim. “But sadly, it has come on this unfortunate day.”

Even as the enforced calm over the city had also silenced their neighourhood, the father would tell the postman loudly how his daughter burned the midnight oil to become a doctor.

“We’re in dilemma,” tearful Lal told Ibrahim in that historic hour when the age-old neighbourhood was about to change. “On one hand, it’s the future of our daughter and on the other, death hovers over us!”

With that, Lal broke down, his shrieks echoing in the hushed alley of Karan Nagar.

Ibrahim could only silently listen to the couple who were desperate to share the big news with their daughter.

“But I do not know whether I should make a trunk call to my daughter and tell her about her selection, or keep it a secret for a while,” Lal continued, weeping profusely alongside his wife.

The postman who had braved curfew and hostile troops on the streets didn’t know how to console the couple at a time when Lal’s tribe was abandoning their homes in a historic huff.

After a while, when he couldn’t take it anymore, he left…

30 years later, that postman is now an aged man. But he still remembers that distressing meeting, with a sense of nostalgia, inside his home in Batamaloo’s Dhobi Mohalla.

As a messenger with an experience of over four decades, he was delivering letters and money orders to different addresses in the city, when Agha Shahid Ali would write a tribute to his homeland: The Country without a Post Office.

Behind that heartfelt anthology mapping the poet’s longing for his homeland is said to be the unattended mails in many post offices in Kashmir—especially inside the General Post Office on the Bund, situated parallel to the poet’s Raj Bagh residence. It’s from this post office Shahid would take home what he called “rejection slips” from different editors of his times.

But such was the phase that even postmen weren’t spared by the warring times. And those who remained active struggled with their routine, as they mainly found themselves indoors due to the situation.

Then, the mails would arrive from different parts of the world. They were mainly distressing letters, enquiring about the prevailing situation. Many others carried assistance in the form of money orders for the conflict-caught citizenry, who were out of work and running out of rations.

As many of those mails remained undelivered, for the paucity of postmen, it apparently provoked Shahid—“the witness”—to dedicate the anthology to his homeland.

But Ibrahim made it sure to deliver those mails, especially money orders to the people.

“Those were the days when shoot-at-sight orders were common,” the postman recalls. “But as a sense of duty, I did manage to disburse many mails in stipulated time as I felt that several families were starving due to clampdown, especially in Downtown, Srinagar which witnessed strict curfews.”

It was the time, Ibrahim continued, when none would muster courage to come out of their houses after dusk. “The unsettling silence would only shatter with the noise of artillery,” he muses.

A scene from the 90s when Ibrahim would regularly come out on the manned streets to deliver mails.

As Kashmir those days heavily relied on postmasters, Ibrahim soon found himself in a different message delivery service. That ‘special task’ would eventually make him one of the significant characters in the conflict zone.

Many Kashmiris who were detained and lodged in different jails had begun sending home letters—detailing their prison plight.

“I remember how armed forces had picked up 23-year-old Kashmiri boy in 1994,” Ibrahim says. “He was the only breadwinner of his mother, Hajeera. Caught randomly, he was awarded a ten-year-long jail-term.”

During the decade long incarceration, it was only pen and paper which connected him with his mother. After every ten days, he used to at least post one letter from Jammu’s Kot Balwal jail to his mother. And Ibrahim would deliver the same to his address, religiously, from 1994 to 2004.

“Those letters consoled his mother during that traumatic period,” the postman’s eyes gleamed with recollection. “She managed to survive for that decade till he was let off.”

Carrying stack of similar letters in his bag, the postman would deliver them to different addresses across the city.

But at a time when identities and addresses were getting lost, Ibrahim was delivering no happy mails. He remembers families breaking down, fainting and crying upon receiving those mails — especially the ones coming from different Indian jails where Kashmiris were lodged.

As a habit, Ibrahim would make rounds of the addresses he knocked as postman. One such follow-up took him back to Karan Nagar, where he had delivered the “happy mail” to the Pandit couple.

Pandits were still leaving Kashmir when the postman went to see Sundar Lal. As he stepped inside the deserted neighbourhood, he imagined a locked gate.

“But my happiness knew no bounds when I saw the Pandit couple inside their home,” Ibrahim recalls. “After a gap of 30 years now, the family is still there living in total harmony with Muslim neighbours.”

Their daughter, whose selection letter was delivered by Ibrahim, at a time when many significant mails were getting lost in transition, is now a reputed doctor.

“A mother of two,” Ibrahim says, “Sundar Lal’s daughter is now working in Europe along with her husband.”

Heartwarming moments like these make Ibrahim feel proud of his profession — that kept communication alive in ‘the country without a post office’.

Like this story? Producing quality journalism costs. Make a Donation & help keep our work going.