India has taken its war in Kashmir right in to the realm of people’s emotions. A conversation with author and academic Mona Bhan.

* This interview is a result of conversations over the past more than three years, mostly conducted before Narendra Modi came to power in India in May 2014, and before the BJP and PDP came together to form a coalition government in Jammu &Kashmir in March 2015.

Kashmir has remained a contested territory between Pakistan and India ever since the British gave up control over much of the subcontinent in 1947. While the struggle for Kashmiri self-determination has gone through several phases since then, state violence and extreme forms of political repression under Indian rule have remained constant. One of the ways in which the Indian state has tried to delegitimize the struggle is by using plurality within Kashmir as a justification for occupation: Diversity is considered as “evidence of intractability of Kashmir’s political divides”.

In India, on the other hand, a similar kind of plurality is a “sign of democratic vitality”. Accentuating difference within Kashmir, however, has not remained confined to India’s state discourse against Kashmiri self-determination. It is a strategy alive and kicking on the ground as well.

One of these strategies is projecting the Shia Muslim population in (particularly) Kashmir’s Kargil province as politically different from (particularly) the majority Sunni Muslims of the Kashmir valley. Another way of ensuring dominance is the massive military project, Operation Sadbhavna, or Operation Goodwill as the Indian army often calls it. Before Operation All-Out—in which the Indian security establishment have prepared a hit-list of over 250 militants to target in order to bring “lasting peace” and has resulted in over 220 killings already from March to August 2017—which began since Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani’s extrajudicial killing in 2016, Operation Sadbhavna was projected by the Indian military establishment as a “cutting edge counterinsurgency strategy”.

However, as we see, a studied evaluation on the ground unravels an extremely complex mix of military dominance, political deception, and psychological warfare. What’s the span, scale, and the ambition of this counterinsurgency project in Kashmir? How is it working, and what is it doing to people in different parts of the state? Under Indian rule, Kashmir remains the most densely militarised territory in the world. Its borders remain perhaps the worst affected—yet almost totally unattended.

It shouldn’t be surprising that during the ongoing standoff between China and India in Donglong, China has raised the disputed nature of another border region, Ladakh, as a geostrategic trump card against India.

Mona Bhan is the author of “Counterinsurgency, Democracy, and the Politics of Identity in India: from Warfare to Welfare?” (Routledge, 2014). An expert voice on the subject, Prof Bhan has worked on questions of identity, development, militarization, and counterinsurgency in Ladakh, particularly post-war Kargil, for more than a decade and a half now. She is based in the US as associate professor of anthropology in DePauw University.

Since 2012, she has been conducting fieldwork in Gurez, Bandipora, and Srinagar on the 330 MW Kishanganga dam to explore the intersections between hydropower, border politics, and militarization in Kashmir. In this interview, she dispels the notion based on the official state narrative that difference within Kashmir is an impediment to political resolution. At the same time she also uncovers the nature of India’s military operations in the border region—and what it seeks to achieve through them—and the attendant project of Hinduisation through organisations such as the RSS.

Nawaz Gul Qanungo (NGQ): In your book, you mention that the Brogpas (a small ethnic minority living in four villages along the line of control in Ladakh) relied on their roles as spies and porters for “inclusion [in] the wider body politic”. You also say that Brogpa social institutions and landscapes “dramatically transformed to accommodate the military’s growing requirement for civilian labour and resources”, isn’t that somehow more a measure of the deprivation, powerlessness, and desperation experienced by a tiny, disadvantaged community?

Mona Bhan (MB): See, the problem is when you speak to people in Ladakh, you often hear people say that “it is because of the military that we have these options like access to health care or roads that open in March rather than in June”. It is unfortunate that people have been marginalized to such an extent that they look up to the problem as a solution. The military is grabbing resources and taking up huge chunks of finances and taxes when these issues ought to be taken care of by a civilian government.

The idea is that since democracy has failed to bring you a sense of inclusion, the military is the answer. The military offers people roles as spies and porters etc., so people see themselves as “included” in the wider “national” community.

Now, one of the implicationsof this has been that people are often forced to revise their own history. A lot of these community members didn’t have a strong sense of national or religious identity until the war. The war, and post-war military labour, demanded a particular kind of rigid identity that conformed to that of the nation state. A lot of these people, including the “war hero” I talk about in the book, had a mixed identity. The war hero’s father was a Muslim from another village and mother a Buddhist, and this was a source of perpetual anxiety. He was now actively obliterating his own heritage and trying to be singularly Buddhist and Indian.

You can understand how having a history of mixed religious identity could be an act of sedition, which the state now had to fight. The sheer memory of having fought for Pakistan at some point in your life became an act of sedition. So as porters, as spies, as war heroes, you had to actively cultivate a very hardened national identity, which in turn relied on your religious identity as a Hindu and Buddhist.

In war time, the military wanted young men from the village to participate in the war. So they raised what they called the First Porter Company in the Kargil war, telling people if they work for them, they would be enlisted permanently in the military. Now that was attractive. So a lot of these young men in the village actively applied for this “recruitment” but it turned out to be a huge hoax. Their labour and their bodies were used for war but once the war ended they were essentially trashed. But at the same time, people were actively contributing their labour to the military because the military demanded that each household send an active young member to fight the war. This is just one way the Brogpa social institutions were transformed to accommodate military labour during war.

Insofar the women were concerned, the military started relying on them to cultivate vegetables and fruit instead of buying it all the way from Chandigarh. This wasn’t what women necessarily used to do in these villages before the war.

The other thing is their land and resources were used to fight the war. Like for instance the Bofors gun required land for installing. So the whole landscape was transformed to meet the demands of the military, and that’s the extent of militarisation. It shapes people’s bodies, ideologies, identities, and even their land and resource use.

NGQ: What’s the population of Kargil compared to the number of armed personnel?

MB: That’s a critical statistic. While 35 per cent of land occupied by the army is in Jammu and 11 per cent is in Kashmir, almost 46 per cent is located in Ladakh (I am sure the statistics fluctuate but the military has a large and ubiquitous presence). So in terms of land, it is largest in Ladakh. But I’m sure the military justifies it because Ladakh is very thinly populated so there’s more available land to be occupied (laughs). Just to give you an idea, there’s a town called Batalik where in 2003 there were more Nepalis, who came to Kargil during and after the war and became integral to the war economy, than the locals in the government’s anti-polio vaccination list.

NGQ: Why were so many Nepalis there?

MB: Obviously for portering for the army. That’s also an indication of how predominantly the villages were serving the army that even the demographics shifted.

NGQ: But Nepalis are not even Indian…

MB: Yes, they are not. In fact, during my stay, there was some controversy around employing Nepalis as porters. So outsiders could be employed by the army at very strategic positions on the border where the Kargilis were not even allowed to travel freely to, for example, their own pasturelands. Also, Nepalis were more pliable since they didn’t have any rights as citizens and could be paid less. Nepalis had more freedom of mobility that many Kargilis who needed official permits to walk around Batalik. It was ironic, and, in many instances, even the military acknowledged it.

NGQ: You talk about the “strategic exclusions” of “[disloyal] Kargili Muslims” and their representation as “incipient terrorists” by the establishment in its extension of Sadbhavna and what it calls participatory democracy. What are they practically being excluded from?

MB: First, Kargili Muslims were excluded from the processes of government. They didn’t have a very well defined role in those processes. Even after the sanction of the hill council for both Leh and Kargil, only Leh decided to opt for it. At the time Kargili Muslims didn’t think that their political aspirations could be meaningfully met within that framework.The Indian government agreed to the hill council so the demands of union territory status for Ladakh could be ignored. The hill council sent mixed messages of communalization and deeper polarization between Buddhists and Muslims in Ladakh, and to an extent between Kashmir and Ladakh as well. Kargili Muslims did not see much potential in the hill council and decided not to form it, until 2003. Kargilis felt that they were not being given their political or economic due. They strongly felt that the hill council was not for them because it would help the Buddhists of Ladakh to finally acquire a union territory status that would marginalize the region’s Muslim population. And also because the then National Conference government under Farooq Abdullah didn’t want the hill council to have too many powers. So Kargilis didn’t see it as a genuine decentralisation of power either.

But in 2003, after Mufti Sayeed came to power and the “healing touch” discourse emerged, the idea was to allocate more powers to the hill council and make it clear to Kargili Muslims that they didn’t have to feel excluded. Kargilis also saw that Leh got massive amounts of money and attention not just from the state but from various NGOs too. These NGOs were also invested in promoting Buddhism as a “non-violent religion” which worked for Leh while Kargilis felt trapped by the ubiquitous image of Kargil as a high altitude battlefield. So, on the one hand, while Kargilis feel estranged from Leh, they also felt that the state government had not been fair to them right from days of Sheikh Abdullah. The LoC was of course devastating. Their ties with Baltistan who they feel very closely aligned with were cut off. The LoC actually dealt a body blow to their culture, but it also weakened them politically.

However, after the hill council was formed, it created yet another tier of politics without necessarily empowering people in meaningful ways. Kargilis felt that it turned brother against brother—too many elections were happening that divided families, and split their loyalties. For a small place such as Kargil, there were four elections in a year creating power nodes within villages, even families.

And the structures of the military remain untouched. The hill council hasn’t been able to provide a very robust alternative to the ideologies of militarism, something it in reality should have been able to do in order for the people to achieve self-realisation.

So for me the hill council was more of a remedial exercise.Unless there’s a meaningful resolution of the dispute, everything the government does is an exercise in management, of managing populations and their emotions just to ensure that these emotions don’t burst into something lethal, the way they did in Kashmir. So you keep these emotions in check through different means,through decentralisation projects for instance that don’t necessarily devolve power as much as they manage emotions. And that’s not a very sustainable strategy.

However, one must recognise that in 2003 Kargilis were very excited about the council. But then, again, it was seen as only a developmental council that had nothing to do with politics. Very quickly, however, it turned out to have little to do with development and everything with politics.

NGQ: When you talk about these strategic exclusions, are these exclusions constant? Is the state constantly engaged in this project of strategic exclusions? What’s the response to it, if at all?

MB: Yes, it is always going to be constant, because the anxiety of the state is. As long as human emotions defy state-scripted identities, the state will continue to work against those emotions. But again, you cannot stop being a Muslim, or a Baltior sever your ties with kith and kin in Pakistan. As long as affective connections exist, the state continues to see the potential of sedition.

That’s why Sadbhavna—“Goodwill”—was the key. You could use violence to quell physical defiance of law, but when that defiance is emotional, when you harbour thoughts that the state doesn’t want you to think, there’s a need to surveil your emotions, your interior selves, the core of who you are and how you relate to the world. That’s why Sadbhavna is so dangerous. It’s not just about disciplining the bodies but the hearts as well, and that’s why “heart warfare” and the logic of “heart doctrine” is so pernicious. It’s not “hearts and minds” anymore, because that’s just psychological. The focus seems to be directed toward matters of “heart” and that’s emotional. And that’s the new battlefield. It is about curtailing and confining your emotions to the “right kind”. So you don’t just do the right things but think the right thoughts or feel the right emotions, the right love.

It’s tragic, yet there is resistance. In Kargil, I think every other person is a poet. Kargilis use poetry to question boundaries and connect with the landscape and people they haven’t met in decades but have strong bonds with. These emotions of course transcend borders. You know, borders can only do so much… they cannot rob people of their sense of self-identity and history, something that far outweighs state-scripted templates of borders and identities. A museum in Kargil to me is a testimony to that. To celebrate links that existed in the past, and derive a sense of identity and pride from them and realise an expanded sense of self that’s not limited to being a border citizen, a backward citizen, or a remote Kargili on the fringes of “Indian” territory.

NGQ: What can the long-term repercussions be, particularly talking about strategic exclusions?

MB: Look, a lot of Kargilis would love to have the borders opened. For a lot of people, meeting their husbands, wives, children, whom they haven’t seen for decades now, is a priority. So many are already dead. But for a lot of Kashmiris, that goes against the demands of azadi. The moment you open the border, you are legitimizing it and making it an international border which it is certainly not. But I don’t think the two are or need to be mutually exclusive. For Kargilis, road connectivity or cross border access to a village in Pakistan is critical. As long as these day-to-day struggles are not considered in conjunction with azadi as a larger project, we cannot do justice to these different, albeit related, struggles.

It is a paucity of political imagination that one is read against the other. The fact is these are genuine aspirations and there’s simply an urgent need to resolve the Kashmir issue in accordance with people’s aspirations and take into account the multiple struggles people in the state experience. I am aware that calling Kashmir a “complex” problem is precisely what has allowed the status quo to continue; the term “complex” has been thrown around quite a bit by commentators to undermine finding a just and humane resolution and end India’s occupation of Kashmir.

At the same time, to not recognise the real complexity is also undermining a lot of these everyday struggles people face on the border, who might just want to go across to see their family but are unable to do so. Kargilis show you how being a border resident is different from living in the city, for example, where your experience with the military is qualitatively different. Both need to be ameliorated, but they might require different solutions. One cannot be pitted against the other, and neither can one be used to undermine the other. I know a lot of people in Kargil who were able to go to Pakistan a few years ago. One of the men I met spoke joyously and passionately about his experience of meeting his niece who is now 22 years old. He couldn’t stop talking about it for three hours—now even that can be seen as “sedition” by the state. Or take the example of the night of Shab e Meraj, when I was told by several villagers in Batalik that people across the border light candles and the military thinks they are sending signals across.

So even in the absence of picking up arms against the state, in most likelihood these acts will be read as sedition. No arsenal can dilute this emotional connect, or change the shared rituals, religious allegiances, and emotional relations of people. And that’s the basis of these strategic exclusions, the idea of an inchoate citizen, the incipient terrorist, where there’s always a possibility of sedition. And yes, that’s a constant. But there’s no way you can forcibly annex a people’s emotions.

NGQ: So now you have the Operation Sadbhavna on one hand and decentralisation of power within the state on the other, and the Indian state and the military establishment seeks a certain kind of participation, even behaviour, on part of the Kargilis. And let’s assume this project continues for the coming years, or even decades. As long as the state or the military is achieving what it seeks, what do you see happening to the larger resistance politics in the state in the long run?

MB: That’s a great question. As I said, decentralisation has added just another tier to politics. Now I’m in no way against decentralising power, but I don’t want it to become a way to escape resolving the larger political crisis in the state. Whether you are a Kargili or someone from Leh, people might say that the Kashmir issue is different and not connected to the local issues, but that’s not true. The fact is Kargil’s politics is shaped by what’s happening in the valley—although of course it cannot be entirely reduced to it. So why not recognise the intricate connections between your everyday politics and what’s unfolding in Kashmir. Decentralisation as it is right now is very remedial, trying to maintain the status quo to a problem that needs an urgent solution. On a day-to-day basis, decentralisation may or may not be successful, but what’s more significant is its impact on the larger political framework for the state or its potential to offer substantive ways to restore people’s dignities and histories.

So I see these interventions as actually damaging. It is like having a deep festering wound and you put a band-aid on it. That might hide it, not cure it.

You see this whole narrative that “trouble erupted” in 1989. It’s very reductive and perpetuates a false sense of history. Of course nothing “erupted”, this was a problem with deeper historic roots. But this is what’s supposed to be taken into account and not shoved under the carpet under the slogan of atootang (integral part). A lot of people who were fed on the narrative of atootang did see 1989 as some kind of “eruption”, wondering why Kashmir would suddenly want to break apart.

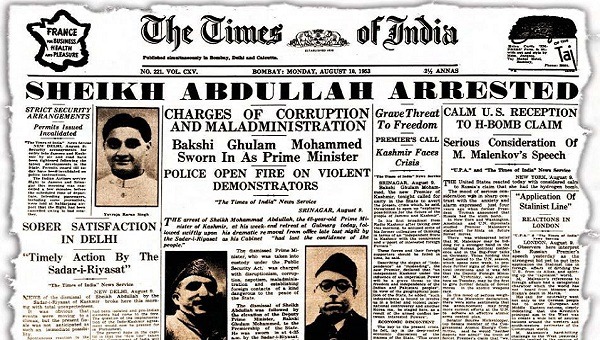

I’m reminded of Raghunath Vaishnavi’s [a Kashmiri political leader (1909-96), and Prof Bhan’s grandfather] prison notes. He spent years in jail when he was part of the Political Conference, after Sheikh Abdullah was deposed and imprisoned in 1953. He talks of particular events from the 1950s and 1960s in his journals. Sometimes it seems that the street scenes from the 1950s or 1960s are no different from what you have today. I’m not saying things are not different. The violence has deepened, the nature and mode of protests have changed. People at the time were trying different strategies to communicate to the government that Kashmir was a political problem and needed resolution. But as long as the real issues are not genuinely attended to, and Kashmir is held hostage, nothing in the way of peace or justice will be achieved.

Now the question what happens in the long run. For the Brogpas, the politics of the RSS is gaining a lot of traction in Leh, which of course comes with its own agendas. Unfortunately, it is hard to say that this is what is going to happen but I see a lot of very regressive things already underway in the region (important note: this conversation was conducted before the Indian Hindu right-wing BJP under Narendra Modi came to power in New Delhi, and before the PDP and BJP formed a coalition government in Kashmir). And when I say the RSS is getting traction, I’m not saying that the Ladakhis can’t see through the manoeuvres.

So for the smaller communities like the Brogpas, the RSS may come and open a school in the village and provide employment to some. Even though Brogpas recognize the RSS’s political agendas, there is a danger of such institutions and their ideologies becoming normalized over time. So I don’t have a definitive answer to your question—that this is what is going to happen if it continues this way—but there are a lot of things that are already underway and I don’t see them as necessarily progressive steps towards a better or more egalitarian politics in that region and I think it’s only going to get worse.

NGQ: What do you think can happen? What can be worse?

MB: That’s a great question. That’s a really good question. What can be worse? I think for me honestly worse can be… (pauses). See, sixty years ago, many Ladakhi families had both Muslim and Buddhist members. You still have names that are both Muslim and Tibetan, it was a very syncretic space, where religion was not the only identity that people associated themselves with. It certainly wasn’t something people would fight and kill for. Unfortunately, what’s happened in the last 60 years, especially after the politics around UT status in Leh, and the boycott that ensued, religious politics has certainly worsened. The divide between Leh and Kargil has deepened. The divide between Muslims and Buddhists has deepened as well. And that obviously plays into the politics of the status quo. It bolsters the politics of difference that the state is ostensibly trying to reduce but is actually encouraging.All this makes the politics in the region seem complex. There is an intended push to frame solutions outside the Indian state’s constitutional framework as unviable. It robs us of our political imagination when we start fighting over religion, ethnicity, language. But I think it’s already taken a very regressive turn, it’s not as if the worse is yet to happen or there’s some apocalyptic scenario that will unfold. I think it’s unfortunately already underway. And I think the most political sense would try to minimise that and contain the damage rather than making it worse unless the political will is to keep it going that way which unfortunately (we know) might be the case.

I’m interested in looking at the processes of state-making, be it through the formation of hill council or deepening of the religious and regional political divide which is ultimately helping the military strengthen its own image.

So how could it get worse… Worse for me is this situation where a boy can call his grandfather senile because he wouldn’t believe the old man had fought for the Pakistani military. So you can envision a scenario ten years from now where somebody my age talking to her grandchild saying “we would have Buddhist-Muslim names in the same household” and the grandchild considers me senile. Such corruption of history and memory is what’s most damaging.

NGQ: One does also recognise the heterogeneity within the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Now, again, if projects such as Operation Sadbhavna continue to be pursued by the state and the military for say another 20 years, along with its attendant perversions that you mention, how do you see the situation in Kashmir panning out?

MB: As long as people keep fighting for dignity, but don’t get it, they will continue to fight for it. That’s a basic human instinct. And that’s what makes us human. Our persistent search for dignity and identity helps us realise our sense of self. Even within Kargil, communities are positioned very differently vis-a-vis the state. Brogpas are positioned differently towards the state compared to the Shia Muslims of Kargil or the Buddhists of Zanskar. So I think it’s going to have a different impact on different people based on whom they chose to align with.

The politics of freedom is also a persistent search for dignity. It is a deeply felt emotion that you cannot curb through violence or counter insurgency mechanisms that kill bodies but fail to kill sentiments. And while you are killing bodies, you might strengthen sentiments, precisely what has happened in the case of Kashmir. So unfortunately it is a situation where Kashmir will stay the same and constantly fight the way it is and Kargilis depending upon how they position themselves vis-a-vis the state will obviously yield different effects, and a lot of these are very regressive, and deeplydisturbing.Like, for example, the strengthening of the RSS. When I started my fieldwork, the RSS wasnot a big presence.But in 2012, it had become far more extensive even in remote areas. So, I think the situation is grim. I don’t want to be a cynic but unless something meaningful is done to meet peoples aspirations,everything that’s done there is going to be remedial or simply something to secure the health of the state or the military. But again, that’s precisely what the Indian state wants but Kashmir’s political status quo has implications for the entire subcontinent, including for India, and India must wake up to this.

NGQ: What is the RSS trying to do?How do you see that problematic?

MB: The narrative of course is that Buddhism is a part of Hinduism and what they are trying to do is co-opt and appropriate the Buddhist ideology. I see this as an attempt to Hinduise the borders. That’s what the strategy is, [that’s how] they started the SindhuDarshan. But it’s become pronounced since the flashflood (2010) which gave an alibi for the RSS to jump in and establish its social welfare centres, their tried and tested strategy in other places too. So in the name of disaster management a lot of these regressive institutions are extending themselves in their lives, which is also how the military works—youfind a crisis situation and you become the saviour, the solution, when you are actually the problem.

NGQ: And what do you see is particularly regressive in this?

MB: Well the whole Hinduisation of borders is the very particular claim to Kashmir. So you are trying to not just claim Kashmir as an atootang of Bharat but trying to trigger a very regressive politics against Muslims in Ladakh, where the Buddhists are being pitted against Muslims and Christians.

Nawaz Gul Qanungo is a journalist based in Srinagar. He is on Twitter @nawazqanungo. Read more on this by this writer in ‘The Hindu’ here, and ‘HimalSouthasian’ here.