When the first resident footfall was traced in the flood basin called Bemina way back in the early eighties, hardly anyone sounded like the prophets of doom—unlike when 2014 floods exposed the farce of the new neighbourhood cropped up at the behest of shoddy planning, rampant land deals and corrupt official practices.

At 75, Asadullah Kumar is one of the oldest residents of flood-prone Hamdania colony of Bemina Srinagar. Over the years, he has seen the change sweeping over the City’s new neighbourhood emerging right from a flood basin.

A restive old city population craving for spaces and floating masses from the countryside availed the land in post-90 haste to form the new housing colony in Bemina. The new neighbourhood went on to redefine the City forever and apparently surfaced the scam after 2014 floods drowned it.

At Hamdania Colony where plumes of dust rise up in a whirlwind, Kumar, a vegetable grocer, watches the hustle bustle on the streets, which used to be a stream and swamp once. He is yet to come out of 2014 flood impact. He points toward the ceiling with his right hand, talking about the level of water that enters his shop every now and then.

The watermarks are quite prominent, telling the tale of recurring damage and fear psychosis with which the residents of Bemina live.

It was 1981, when Kumar’s family shifted from the nearby Chattabal area to Bemina. Then, they had to deal with a different kind of fear rather than the fear of floods. “Only 8 households were living here at that time,” says Kumar. “There was no specific colony. It was an open space and we would be afraid to go out in dark.”

Then, Kumar says, it was quite a scene in Bemina. Migratory birds like the Pintail Duck—Pachin in Kashmiri—were regulars in Bemina. “I would try to catch them in the front yard of my house constructed on 10 marlas of land,” he says. That piece of land which became his new address wasn’t suitable for construction. It was a paddy field sold out to him by a landlord. To make it worth living, he ordered 96 truckload of soil to fill it. For a very long time, he felt—as if he was living in a countryside area, bereft of any urban character.

City would end near the Batmaloo roundabout. Beyond that, swatches of swampy area would be called Bemina, stretching up to Budgam. While corn and Baegl-e crop would be grown on its right side, Bemina’s left side was completely marshy — until Hamdania colony cropped up in the early eighties. What was otherwise an illegal and unnatural City extension, got government support.

During Farooq Abdullah’s first term as chief minister, Kumar got a transformer and water connection in Hamdania Colony. But soon, a big flood hit the area, making a mockery of the sudden human intrusion into a flood basin. It was 1984 and the government of the day—instead of relocating the handful households—encouraged them to retain their spaces in a flood channel. On the insistence of Kumar and his neighbours, the government constructed a floodgate.

Years later in 2014, as floods of a massive proportion hit Srinagar, the households including that floodgate would be torn asunder.

After the floodgate, the residents demanded roads. By the dawn of turbulent nineties and subsequent changing social order in Kashmir, the City periphery began populating.

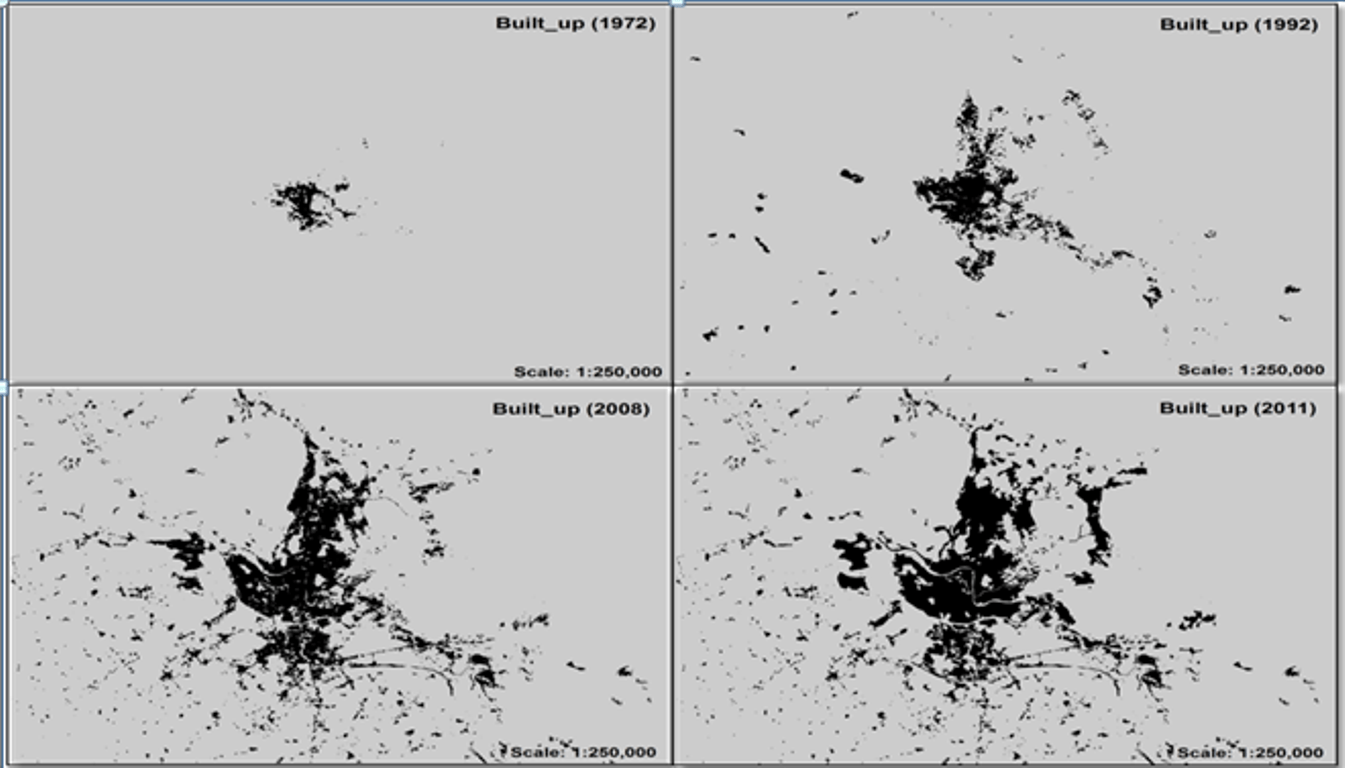

Paucity of land in Srinagar made Bemina the first obvious choice for people. Slowly from the swamps, colonies cropped up—right under the nose of the authorities. By 2000, the new resident footfall was so massive that it changed the swamp forever. One of the persons witnessing this paradigm shift “at the behest of brokers and bureaucracy” is Mohammad Ashraf Bhat.

A resident of Tengpora, Bhat first bought land in 1995 from a landlord. Then, Tengpora was a farmland where his kids would spend hours exploring it, playing with tadpoles and taking out water chestnuts from it.

“Over the period of time,” he says, “that natural habitat began shrinking as housing clusters cropped up.” In the guise of massive construction, Bhat says, Bemina was heading toward devastation. As sand and cement entered, the vintage recreations ended.

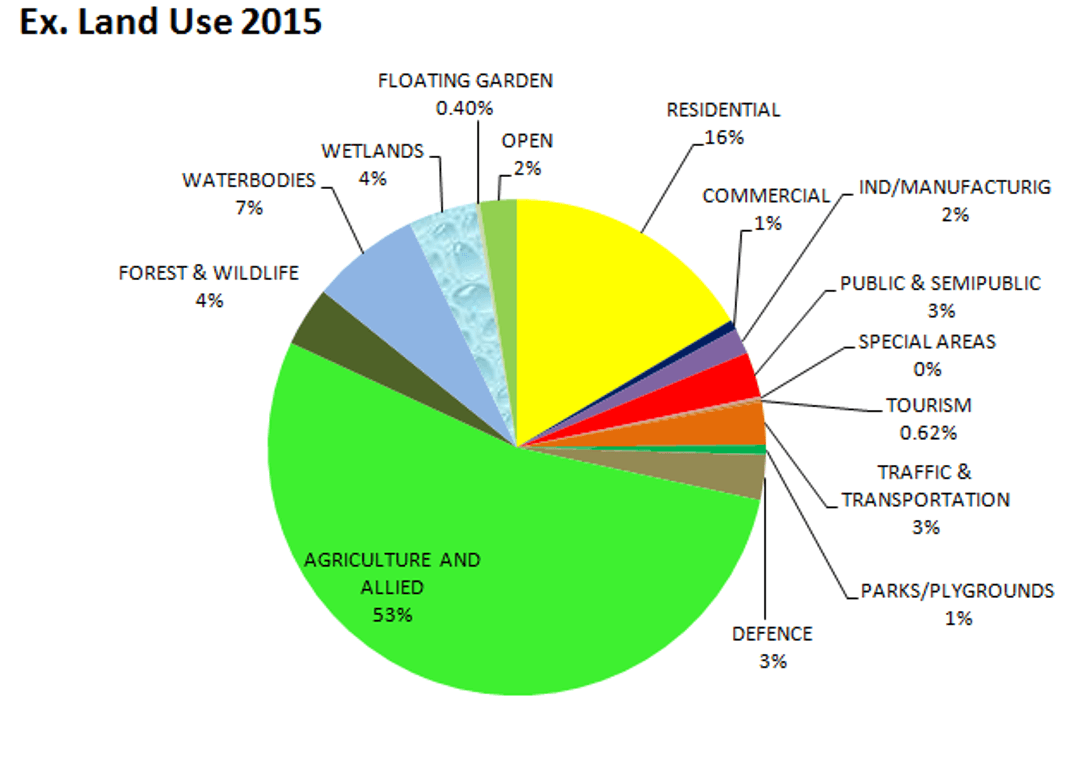

Bhat recalls how a stream in the Hamdania colony would be frequented by anglers. With time, the government drove most of its machinery right into the heart of the flood channel. For policymakers, Bemina was now an alternate address to government encampment: Srinagar Development Authority (SDA), Forensic Sciences laboratory, 100 bedded maternity Hospital (proposed), JK Board of School Education, Degree College, Govt medical College and even the Haj House.

Besides the housing colony and official addresses, Bemina was also becoming a commercial hub. “Being nearer to the city centre Lal Chowk and other localities,” says Naqeeb Ahmad living in Bemina’s Hamza colony since 1997, “Bemina got filled up quickly and housed mixed population.” Around 25 percent of the present population in Bemina was living there when he shifted in the area.

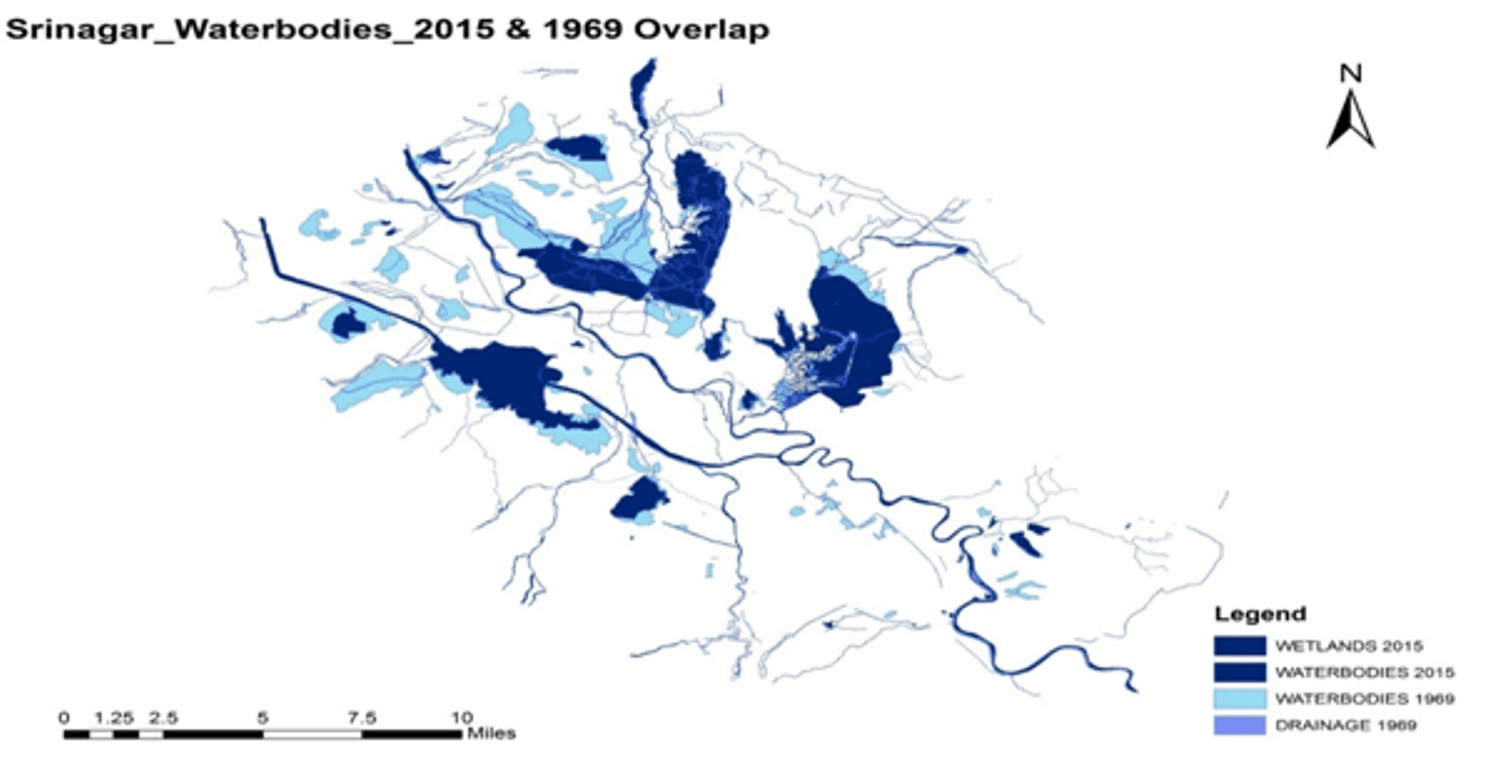

But the emergence of Bemina triggered woes in the larger urban population in Srinagar, with pundits and planners terming it an unnatural neighbourhood. “Being a huge flood basin,” says Khalid Bashir, historian-author, “Bemina would retain surplus water from the Jhelum during floods, thus reducing the flood threat in the City. But now, its filling has endangered the security of Srinagar.”

In the old map of Srinagar City, probably of Dogra era, the Nowgam area in that map was shown as Nowgam ‘lake’, Bashir says. “It all used to be marshy like Hokarsar. Rain excess and flood water used to be retained by this very area, reducing pressure in River Jhelum.” The Kandzaal area in Lasjan used to be breached and this water would follow the natural course then. “But now, the very present shape of Bemina is a clear undoing of the safety valve of Srinagar,” the historian rues.

The problem with Bemina lies with its left side, says Mir Javid Jaffer, former chief engineer IFC. “Rajbagh was also a flood basin,” he says. “Filling such lands cause less water expanse and vulnerability to natural hazards.” In nambals—or, the swamps, he says, the issue of silt up and encroachments is very common. “It’s a 50-50 as far as the safety of Bemina is concerned now,” Jaffar says. “Within a couple of years, if it is worked on, it will be safe.”

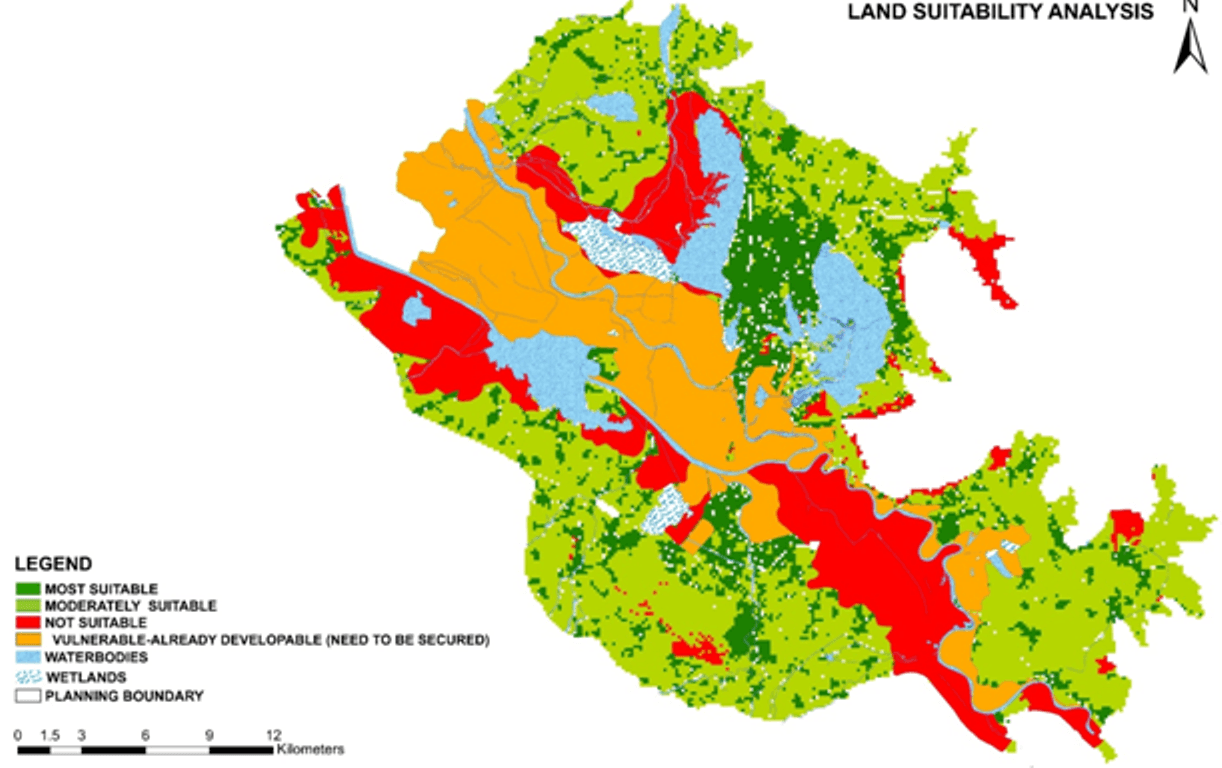

Maintaining the status quo on Bemina looks tad impossible in view of the land suitability in Srinagar and big garrisons occupying the prime and natural extensions of the City.

“Other than Mehjoor Nagar, Lasjan and Padhshahi Bagh, Bemina is a notified flood zone,” says a serving IFC official, wishing anonymity. “Till date, the notification has not been revoked.” But the government, as the common notion goes, is still pushing people towards these areas. “In Bemina’s Sharjah Colony, the government on auction sold one plot of land for Rs 86 lakhs (5000 ft),” says Naqeeb, a Bemina resident. “The government is neither doing anything on the ground nor helping vacate the vulnerable areas. It’s a big scam.”

The concerned departments—Srinagar Development Authority (SDA) and Irrigation and Flood Control (IFC)—are simply passing the buck. While SDA calls Bemina “just a drainage problem”, the IFC officials say they have no authority over SDA. “Ironically, SDA’s office is in Bemina,” says the IFC official. “It has been classified as vulnerable area, which can get submerged if large precipitation takes place in higher contours and a flood of high magnitude hits.”

Amid this apathy, the resident footfall in Bemina is mounting. Since 2010, Naqeeb says, people from Downtown and Indira Nagar have become new entrants to Bemina. Even the Dal dwellers have been shifted in this large swamp.

In the face of it, prophets of doom (that many pundits and policymakers of yore have now become) are warning of an insecure future of the historic city of Srinagar. Undoing of the very idea of Srinagar has indeed costs. And Bemina being one such silent cost is likely to tear asunder—as and when—Jhelum loses it, again.