Packed with devastating stories of human tragedy, Kashmir has apparently become a big sanctuary of sorrow where people wither in longing for their killed ones. One such family in Pulwama is caught in longing since the last fall when its promising son running his father’s tea-stall was silenced.

Signature banter has long gone from a Pulwama tea-stall, where the weary travelers and tea aficionados would have a great time till the last fall. Then, its teen vendor—a happy-go-lucky boy and a delightful company—became a dead count, leaving behind the hushed tea-stall under the care of his equally sorrowing sibling.

Since that 2016 September day, his mother has been in the middle of the unsettling routine…

She’s persistently shedding tears for her teen son, who was taking care of her after his father’s death — by running his tea-stall and perusing his studies simultaneously. But the previous summer’s death cycle consumed Haleema’s hope to an extent where she is unable to make peace with her fate.

One year later, the name Basit is still scribbled afresh on a narrow, shabby tin-gate of her house. As I entered, I saw a young girl in the courtyard of a rundown two-storey house. On being asked about the Basit’s family, she directed me to a part of the house, separated from the rest by a boundary wall.

A day before, on his first death anniversary, hundreds of people had thronged his house to pay their homage.

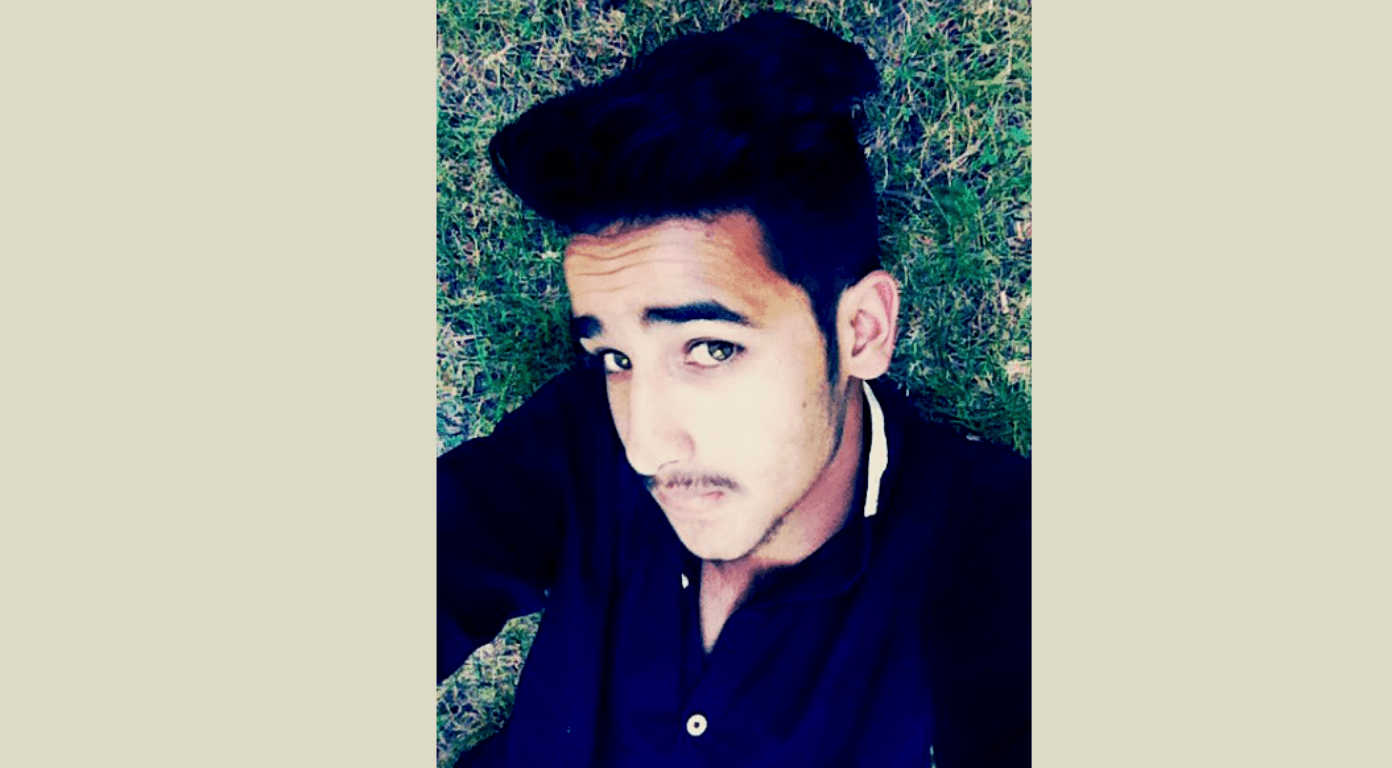

Slain 14-year old Basit

But now… a deafening silence prevails.

Every step towards the entrance of the room evoked in me a strong sense of fear. Nerves never felt so jittery. The aura of gloom was wafting through the house. Inside, few utensils were put in an array at one corner of the room. On the other corner, a pale looking woman with green sunken eyes, draping a white dupatta was gazing through the window of her room.

Every space of that room seethed in sorrow.

For a moment, the woebegone woman at the window was oblivious of my presence in the room, until a girl, her niece, informed me, “she’s the mother of Basit, Haleema.”

Haleema isn’t stepping out of her house since her boy was taken out as a martyr in a massive funeral from her modest home, amid her earth-shattering shrieks. All she does now is spend time doing household chores and tendering to her vegetable garden in the backyard of her house.

By afternoon, her family members often spot her sitting in a corner of her room, sobbing. The scene leaves everyone with moist eyes.

Her 14-year-old son from Dalipora Pulwama was a fun loving, courageous, optimistic boy who used to live his life on his own terms. Despite being from a poor family, Basit was enrolled in a renowned institution by his mother, said his aunt, Sakeena.

Basit’s mother Haleema

On Sep 5, 2016 morning, Basit went to his maternal home to meet his mother. After spending a day with her and his aunt, he went out to meet his friends.

“Little did his mother know that it would be her last meeting with her son,” said Sakeena with a palpable anguish on her face.

Basit was playing cricket in a nearby alley when a teargas shell hit his head.

The moment Basit fell on the ground, his friends surrounded him and rushed him to the hospital.

‘My mother is in my maternal home, tell her…,’ Basit mumbled to his friends as the pain began to muffle his voice.

The yearning to know what Basit had to tell her at that time is entrenched in her psyche. The unsettled thoughts of that moment persists.

Haleema fasted the days Basit remained on the ventilator, in a belief that he may recover. While her son was battling for his life, she used to cry without uttering a word for days, staring at Basit, her hope, who had suffered deep brain contusions.

After remaining in a state of comatose for 10 days, Basit died, leaving Haleema wretched. Since then, she has been living with her elder son and her niece.

Before her son, Haleema had lost her husband due to prolonged illness in 2015. A sole bread winner of the family Haleema’s husband ran a tea-stall to feed his wife and sons.

After he died, she was forced to leave her home by her in-laws. Both of her sons stayed with their paternal grandparents before growing family troubles and day-to-day hassles forced them to live a destitute life with her.

During that tough time, it was Basit who used to give his mother hopes of a better life. ‘Soon life will change for us,’ Basit would tell her. It was then he decided to rerun his father’s tea-stall along with his elder brother.

“It was painful to see them work at the age when they should have been going to school,” said Haleema’s sister. “But it’s what the circumstances demanded.”

Basit elder brother, who now runs the tea stall.

Among the two, Basit was the wittier and studious — always meaning his business. Being lively made him the main attraction at his tea-stall. But back home, his outward forays had somehow ebbed Haleema’s grief.

“But she wanted Basit to get a better education, so in future he would support the family,” continued Sakeena.

Basit became Haleema’s support at a time when her unsupportive and indifferent in-laws had badly distressed her. After his demise, she is back to square one.

“I sometimes wonder what kind of people we live around who sever the relations with you when you need them most,” said a neighbour vehemently.

No one has tried to reach out to her with help. People visited her house on Basit’s first death anniversary only because she happened to be the mother of a martyr. All they did was to pity her.

“She doesn’t speak much to anyone since Basit died,” Sakeena said. “Losing her son to the conflict has taken a toll on her life so badly that she has stopped hoping anything better from life now. The string of tragedies she has gone through has made her numb and silent. She has become a lady who couldn’t narrate her own ordeal.”

Two demises in two years have now made Haleema’s 17-year-old elder son—who had left his studies much earlier—as the sole owner of the tea-stall. Unlike his brother, he finds it hard to give hope to his mother — for she lost it in the last fall, when the tea-stall lost its lively vendor.